A neighbor once told me that a woman died in my house. From then I was constantly looking in my house for signs—every creak was a footstep, every sound was a whisper, a loud scream. My mother says that the way Americans see death as a horror only tells half the story. The other half of death is called memory, fantasy, ancestor.

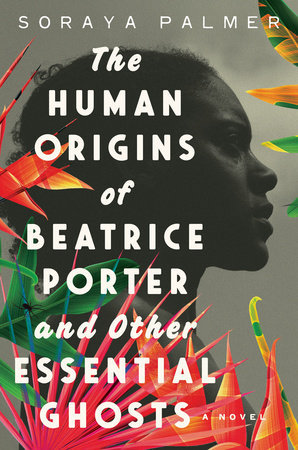

My novel, The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, is filled with—you guessed it—ghosts. Some come from the Caribbean folklore I grew up with: the Rolling Calf, Mama Dglo, and Ol’ Higue. But my book also features other ghosts: the physical presence of colonization haunting the island of Trinidad and Jamaica, and the haunting that comes from grief and regret. But more than that, there’s the family of Black women that I see as my novel’s heartbeat that tell stories of their characters’ histories, their deepest secrets, their wildest dreams.

Throughout time, Black women have told ghost stories as a way to record the histories we were often left out of. Stories of trickster spirits have been used to explore the small ways we take back our power from our oppressors through trickery. Like the story of Anansi tricking Tiger and Lion into becoming the god of storytelling. Like the story of replacing the master’s sugar with cyanide. In literature, we have used ghost stories to tell the things we are sometimes too scared to hear about: like what happens when we become possessed by the traumas of our ancestors, or the terror in becoming a mother during slavery, or the complicated grief that comes from losing the person who raised you. With that said, here is a list of seven contemporary Black women authors who have continued this long tradition of Black ghost storytelling.

The Ghost as a Haunting Paranoia

White is For Witching by Helen Oyeyemi

Unlike other haunted houses, this one speaks. The house warns its readers as well as its guests what may happen if we step out of line. A mannequin pushes a poisonous apple into the mouth of a Nigerian housekeeper. An elevator traps the child of an undocumented housekeeper and gardener all night long. In the background of these hauntings, there are other horrors happening: The fourth Kosovan refugee has just been stabbed, another detainee at the Immigration Removal Center hangs themself.

The house, like the family that lives there, develops a paranoia of everything outside their four walls, showing us that what lies beneath liberal white politeness may only be the sinister fear of the unknown—the same fear that erupted into Brexit eleven years after this book was published. The white and wealthy owners of this house decide to convert their home into a bed and breakfast, only to find that it is not kind to outsiders—specifically the Black immigrants that pass through its walls. Author Helen Oyeyemi, who was born in Nigeria, but raised in London, creates a ghost story that holds us hostage in its terrifying splendor.

The Ghost as Forgotten History

The Jumbies by Tracy Baptiste

The Jumbies is one of those books I wish I had as a Caribbean girl growing up in America. Trinidadian author Tracy Baptiste is a former teacher who writes in her author’s note that she, like myself, grew up not seeing Caribbean folklore represented in children’s books and fairy tales. It is one of the few books on this list that can be enjoyed by children and adults alike.

The novel is inspired by the Haitian folktale, “The Magic Orange Tree,” and takes place on an unnamed island where townsfolk are growing afraid of the jumbies who they see as coming to take over the island. Yet if you asked the jumbies, they are the ones who originally inhabited this place and are, in fact, the ones who emancipated everyone else from slavery. Through this imagined history, Baptiste demonstrates that the history of the Caribbean is wrapped up not only in slavery and colonization, but also in emancipation and ghosts.

The Ghost as the 8th Stage of Grief

What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons

In Zinzi Clemmons’ novel, Thandi and her father grieve their mother, who has died of cancer. Clemmons weaves seamlessly between moving anecdotes of grieving her dead mother, meditations on racism, and original chartings of the seven stages of grief.

At one point, Thandi tells us that “The most important aspect of the ghost is the need that creates it.” The protagonist makes the decision to create a ghost out of her mother in order to help herself grieve, showing us that loneliness can create the feeling of haunting, whether it physically exists or not.

The Ghost as Your Deepest Regret

“Old Habits” by Nalo Hopkinson

Ghosts wander a Toronto mall for all eternity, forced to relive their deaths each day. The unnamed protagonist thinks about the stupidity of his death, having been caught in an escalator due to a newly bought silk tie. These ghosts are hungry for life, and for the smells, tastes, and sensations they no longer possess. One teenage girl who died by hitting her head in the mall bathroom can still remember the smells of food and perfume. This girl gets literally devoured by the other ghosts who wish to consume her memory. When they are finished in their consumption, the teen ghost vanishes into nothing.

This short story, originally published in the Science Fiction & Fantasy anthology, Eclipse, is written by the first Caribbean fantasy and sci-fi writer I was ever exposed to, Jamaican-Canadian author Nalo Hopkinson. Hopkinson, known for re-telling Caribbean ghost stories, wrote something about the ways ghosts can be used to explore regret and the small pleasures we take for granted in being alive.

The Ghost as the Things that Get Left Unsaid

“Second Chances” by Lesley Nneka Arimah from What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky: Stories

Sometimes we think that if that one special person came back from the dead, we would be able to say the things we never could when they were alive. Not is the case in Lesley Nneka Arimah’s short story where Uche wakes to find her mother has stepped out of a family photograph after having died eight years earlier. The incredible absurd humor of Uche’s father and sister’s nonchalance at seeing their mother and wife return from the dead, mixed with Uche’s unexpressed anger and grief was, in fact, one of the many inspirations for my book. Despite this unusual and, perhaps, miraculous opportunity, Uche finds she is still unable to let go of the hurt she’s held onto towards her mother. It is a meditation on the grief of losing someone, but also of the grief a daughter experiences in not feeling good enough.

The Ghost as Family

These Ghosts Are Family by Maisy Card

In the Paisley family, every character has its own ghost. Abel Paisley takes on the identity of a dead man, becoming, in effect, somebody else’s ghost. His life becomes a haunting absence in the lives of his children, his ex-wife, and the family of the ghost he replaces. His daughter, Irene, is possessed by her abusive dead mother, Vera, and winds up running into the rain naked to relive a painful childhood memory. His son’s white wife, Debbie is haunted by her slave owning ancestor that causes her to have increasingly disturbing nightmares and drown his priceless journal in the river. Abandoned daughters in Jamaica begin to shift into Ol’ Higue, the spirit who drinks the blood of babies and takes off her skin at night. Jamaican American author, Maisy Card beautifully weaves these ghost stories together to create an extraordinary narrative on forgiveness, past trauma, and what it truly means to be family.

The Ghost as a Mother’s Deepest Shame

Beloved by Toni Morrison

What else is there to say about one of the most famous ghost novels of all time? Also known as the foremost historical fiction text on U.S slavery, Beloved actually takes place seven years after U.S emancipation. As a reader, you do not always know whether you are in the past or present of these characters’ lives. The memory of haunting (or what Toni Morrison calls rememory) becomes its own terror, perhaps even more powerful than the thing itself.

The haunting begins as many ghost stories do—through the house. The house, described as spiteful, shakes and screams all the pain that it absorbs. At some point the characters believe they have cast the spirits out, but what enters their home next is even more frightening. For in Beloved, the thing you most want to forget will always be the things that comes back to haunt you—the scar in the shape of a tree you received from an angry slave master, the iron bit they fastened to your mouth as punishment, your daughter’s corpse after you slaughtered her. Or perhaps what haunts these characters most of all is the shame of American history we most want to forget.

.jpg)