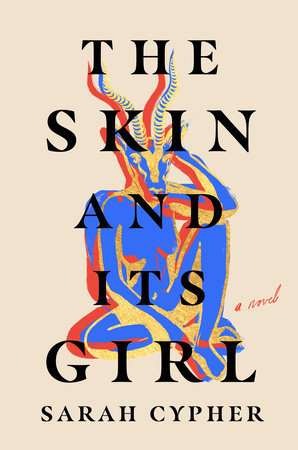

In The Skin and Its Girl, my writing about Arab identity is driven both by a rich personal and cultural storytelling tradition and by a perhaps-endemic Arab American anxiety about how our stories are told in the West. I inherited, without really knowing I was inheriting, an existential comfort in the storytelling my jiddo saved for the airless time after meals, when the dishes were clean but Jeopardy wasn’t on yet, or the cookout was over but the fire was still hot and no one quite knew what to do before it was time to eat again. His was a style handed down from the old country but honed among his steel-mill crew, careful to note who was a good egg and who was the bad apple, and his stories were capable of unfolding to fill a temporal container of any size.

Structured by repetition, confidence, and deliberate uncertainty about whether the eventual resolution might ultimately break toward realism, absurdity, or a mere punchline, the stories riveted me. They also influenced the sort of tales we cousins invented for each other, straddling reality and fabulism. As I began to write seriously in the early 2000s, fiction from a literary magical realist vein felt natural. But when I began to seek more writing about my ancestors’ part of the world, I found a lot of it distorted by an Orientalist lens—that colonialist hangover that preserves racial bias in portrayals of SWANA cultures.

The problem has a root in Sir Richard Francis Burton’s (in)famous 1885 translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. No one skewers it better than Diana Abu-Jaber, who writes in Crescent that the project is “his famous, criminal, suggestive, imperial version of Victorian madness dissolved in the sky over the Middle East.” Today, it still inspires writing directed at Western audiences because its stories are so recognizable, and even novels critical of its influence often reckon with it anyway. Yet for as many stories as Sheherazade tells the sultan Shahriyar, there are other ones that preserve, by turns, the humor, adventure, profluence, and moral instruction of a broader oral folktale tradition. Some of these stories appear in lesser-known works; for example, when writing The Skin and Its Girl, I found inspiration in the Palestinian Arab tales recorded in Speak, Bird, Speak Again (Sharif Kanaana and Ibrahim Muhawi, 1989).

I’m eager to share these seven novels. Familiar figures haunt their edges, but what feels like home to me is the way they engage their audiences, subtly teasing and feinting and coaxing us along until we find ourselves transported to an expanded world. I learned so much from these writers, particularly in how they use degrees of postmodern, self-aware storytelling to counter-colonize the narrative and reclaim cultural agency.

Arabian Nights and Days by Naguib Mahfouz, translated by Denys Johnson-Davies

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) spent an extraordinarily prolific career in Cairo and is, so far, the only Arab writer to have won a Nobel Prize in Literature. For his deep concern with Egyptian politics and his allegorical writing style, he shares with Salman Rushdie the unlucky distinction of surviving an assassination attempt brought on by extremists’ reaction to his work.

Borrowing from the traditional style of The Arabian Nights, this loose sequel picks up when the sultan Shahriyar chooses to marry Shahrzad following her life-or-death storytelling gambit, which has saved her life and the lives of many others. The sultan now commits himself to a leadership style that uses less rape and murder, but the personal transformation does nothing to change his city’s fundamental corruption, its governors, or the merchants who have profited from a lifetime of favors. Shahrzad says “[o]nly hypocrites are left in the kingdom,” but then genies begin appearing to various characters, coercing morally ambiguous chaos from her husband’s toxic legacy.

It’s one of the novel’s modernist ironies that its most fantastical element—the genies—provokes the novel’s most cutting realist critiques. The premise relies on Mahfouz’s contemporary reader, specifically an Egyptian reader, with whom the experience of living in a corrupt and hypocritical system is intended to resonate. Bound by a firm philosophical thread, its episodic chapters are propelled by the complexity of the wish for a more ethical society. Mahfouz writes in a cool, controlled tone; the original text serves, on one hand, to contain and magnify his critique, and on the other, to slide it behind an engaging screen that renders his protest indirectly, just as Shahrzad’s own storytelling protested the sultan’s cruelty.

The Hakawati by Rabih Alameddine

When Osama al-Kharrat returns to Beirut after 25 years to be with his terminally ill father, he reenters a family in which he has long struggled to find his place. Politics, atheism, and sexuality are all taboo, and Osama’s communication with his father has been frosty since immigrating to the United States. This terse situation is a far cry from where it began long ago, with Osama’s gregarious pauper of a grandfather, whose skill as a traditional storyteller (“hakawati”) impressed a local bigwig enough to earn him the official surname al-Kharrat, fibster. Storytelling is in Osama’s name and in his blood, and as the novel weaves in and out of traditional-sounding tales, we follow a dizzy number threads that inter-borrow emotional notes. Osama, a first-person narrator, uses these stories to give his grief, familial love, and outsider identity their place when straightforward speech does not.

Inside its realist, short-timespan framing, The Hakawati is narratively agile, rich, and often hilarious. Incorporating family lore and fabulism, the stories draw on mythology, religious narratives, and characters familiar across the region. We see tales within tales, adventures within adventures, a cyclic storytelling style that also appears in The Arabian Nights. The style compares to the arabesque, whose ornate patterns repeat and occur within other repeating patterns, such as in music; it also harkens to a day when reciting a good yarn might take weeks or months. In my reading of the novel, I felt in the stories’ ever-subdividing complexity Osama’s wish to extend the amount of time he had left with his dying father.

All of Alameddine’s novels draw on his Lebanese American background. Nowhere else, however, does he sublimate reality into fabulism to such a degree, and so sublimely. He demonstrates not just how traditional storytelling can hold contemporary themes, but also how high the stakes are for his character in his father’s last days.

Crescent by Diana Abu-Jaber

Written in the pre-9/11 U.S. but published in the years immediately afterward, Crescent pairs a sensuous, realist narrative with “the moralless story of Abdelrahman Salahadin,” a fable that “is deep yet takes no longer to tell than it takes to steep a cup of mint tea,” or so the teller assures us.

In Abu-Jaber’s body of work, food and cheeky father-figures abound. Here, Sirine is a 38-year-old chef who lives in West L.A. with the Iraqi uncle who raised her. Their peace is disturbed when she falls for Hanif, an Iraqi political exile who soon deserts her for a risky return to Baghdad to help his family. The relationship makes Sirine more interested in her “Arab” identity even as the novel criticizes the essential emptiness of such a broad term. It does so by using a second, seemingly independent fable told by Sirine’s uncle. The self-aware tale of Abdelrahman Salahadin draws on the cadence of an oral storytelling tradition, following a mother who sells herself into slavery to Sir Richard Burton find her missing son. The tale meanwhile aims jabs at Burton, Hollywood, and Western racism, landing punches with strategic humor.

The novel was published in a time where anti-Muslim and anti-Arab bias were no less ingrained in Western culture than they are today. Its two storylines twine around those biases, pulling them apart piece by piece from two literary directions. In Sirine’s narrative, the realist storytelling conventions of a Western fictive tradition embody and complicate the day-to-day experience of having an Iraqi immigrant family. Meanwhile, the fable invites us to loosen our grip on that reality just enough to for it to work its magic, upending expectations about Arab femininity, agency, and identity.

Dreams of Maryam Tair: Blue Boots and Orange Blossoms by Mhani Alaoui

Situated with one foot in fable and one in the dark times of the 1981 Casablanca Bread Riots, this debut novel uses its inventive powers as a form of political resistance.

Multiple storylines braid around italicized sections featuring a wizened Sheherazade, who sits outside of time narrating to a young girl. In the main story, we meet Adam and Leila, an unlikely couple: Leila is a daughter of a wealthy and influential Casablanca family, and Adam is a poor scholar. Unable to conceive and unsure what the future holds, they feel the passion in their marriage draining away ever since they’ve returned from London. Casablanca itself struggles under a similar inertia, stuck in an economic depression and “forged in second-hand steel, barely able to resist decay.” The narrative is at its most surprising when the armed authorities who beat, imprison, and murder the city’s inhabitants turn out to be actual winged monsters. And because of them, after Leila’s imprisonment and rape, a daughter, Maryam, is born. Sheherazade foretells that Maryam, who rides a magic bicycle and can commune with the city’s fabulist creatures, will wield a power to change everything.

The outside-of-time narration gives the rest of the story a sense of being fated, almost immobile. Sheherazade’s character is a straightforward borrowing from The Arabian Nights: at last independent of any earthly power, she once again holds many narrative threads in her hands, and she once again uses them to weave a story capable of altering a city’s bloody fate. Alongside Maryam’s puckish character, Sheherazade’s retelling of old myths, such as an alternative Adam-and-Lilith creation story, opens up a space from which the power of the imagination can shift reality for the better.

The Night Counter by Alia Yunis

Taking a lighter tone than many of the books on this list, The Night Counter tells the story of Fatima, a Lebanese grandmother living with her grandson Amir in L.A. a few years after 9/11. At its core, it’s about the evasions that undermine love. A grieving mother, Fatima divorced her husband after sixty-five years of marriage and is now determined to spend the remaining days of her life attending funerals and stubbornly searching for a wife for gay Amir. She’s lodged in the past, waxing poetic about an idyllic village in Lebanon. Nights, Amir hears her telling stories and wonders whether she is losing her sanity—but in fact, only the reader knows that she’s speaking to the apparition of Sheherazade.

This is the novel’s distinctive magical realist conceit: After arriving in L.A., Fatima began seeing Sheherazade in her window each night. The famous storyteller wanted to be a listener, and Fatima obliged, resigning to a belief that after the 1,001 nights are done, she’s fated to die. Yunis shields the narrative from its risks with deadpan humor, and now that only a handful of nights remain, Sheherazade is weary of Fatima’s repetitions, cajoling her to talk about the love she won’t admit to ever having felt. The light touch allows Yunis to probe these more painful spots in the family’s history.

Her humorous tone also allows the novel to juggle some traditional ideas in a contemporary context, such as the novel’s competing views on the role of fate in its characters’ lives—an important philosophical element of The Arabian Nights. More often, however, Sheherazade is (intentionally) cartoonish, such as when she travels by magic carpet to observe Fatima’s many children and grandchildren. But this choice helps Yunis mark a clear path between so many characters, preventing the reader from buckling beneath the effort to keep track of everyone. As a result, the novel can play with the many forms Arab identity takes in the family, pushing back against the monolithic exoticism of the original text.

Pillars of Salt by Fadia Faqir

Faquir is a Jordanian-British writer, and according to her mentor Angela Carter, Pillars of Salt offers a feminist vision of Orientalism. It’s a dark vision, at that: two women are confined to a Jordanian asylum, sharing a room, and they endure the days by telling each other their domestic stories of misogyny and abuse. Maha, a rural Bedouin woman, relates the tale of her husband’s death fighting the British, and her subsequent misfortunes at the hands of a lecherous brother. The other woman is Um Saad, whose more urban life offered her no more protection from violent patriarchy.

While the novel is engrossing both for its depiction of these two women’s lives and for its ability to capture the Arabic idiom in English, its use of a third narrator is what sets it apart as a postmodern critique of a particular kind of narrative. Speaking to an implied group of listeners, this third narrator calls himself Sami al-Adjnabi (“the stranger,” in Arabic) and his chapters are all titled “The Storyteller.” The pairing is intentional, as his voice picks up the bombastic cadences of Burton’s translation of The Arabian Nights and other Orientalist texts that were written to “interpret” and exotify Arabic-speaking cultures for Western audiences. This narrator inhabits only the margins of the women’s stories, distorting and misunderstanding them, all the while swaggering and insulting the women as temptresses deserving their punishments.

Faqir writes from a specific resistance to a text she positions as calcified and pandering. Um Saad herself tells Maha the traditional tales are all but useless in their own predicament: “I am not a character in One Thousand and One Nights. … I will never be able to roll into another identity, another body, travel to better times and greener places.” Of all the layers of their entrapment, the Storyteller’s distortion of their experiences seems to be the cruelest. And what makes this vision so dark is that though the novel gives these women limited agency as their own storytellers, they are still confined to a madhouse with an audience of only one.

The Moor’s Account by Laila Lalami

Based on a true story, Lalami’s novel is narrated by Mustafa al-Zamori, the first African to explore the New World. Remembered as Esteban the Moor, he was enslaved to a conquistador and thus became one of four survivors of an ill-fated Spanish expedition to Florida.

As the party treks deeper into tribal territories in a fever-search for gold, Mustafa records the men’s abuses and failures alongside his own history. This is done in episodic chapters, each one titled as “the story of” an event. The novel is modeled after classical Arab travelogues, but at times it also takes on the dimensions of a traditional tale, like light catching the cut of a gem. It shines most often where Mustafa relates the rise and fall in his fortunes that led him to sell himself into slavery. As a believing Muslim from the city of Azemmur, he views the episodes of his early life on a moral dimension, whereby fates are written and human follies are punished. (Before his city fell to the Portuguese, he was a merchant who sold slaves.) The traditional stories and proverbs that initially skirt the novel’s margins, however, become central: Mustafa turns to the power of storytelling for agency, wielding it to record a more truthful account of the disastrous colonial expedition and then to trick his enslavers, becoming the clever hero who outsmarts a stronger enemy.

The novel uses a more classic approach than the other books here—Lalami dissolves most of the traditional storytelling style into the main narrative, drawing less attention to it as a self-aware element—but it is a fitting conclusion to this list. I can’t help but think of Sir Richard Burton’s intention that his translation serve as a serious ethnography of Arabic-speaking peoples, and how profoundly he blundered. No book can undo the past, but The Moor’s Account takes special care with Mustafa’s portrayal of Native Americans. It reminds the reader that these tribes were wiped out twice: once by violence and again in American culture by a colonizing story. Like the Apalache women who raise a cry in response to the rapacious soldiers, the novel has “made witnesses of us,” and its counternarrative warns against the violence—and insidiousness—of a single story.