In 2016, nine years ago, I published a list of forthcoming books by women of color that had piqued my interest. As a novelist and occasional critic, I was interested in looking for such books to read and, perhaps, review. Given I’d had trouble finding as many as I’d hoped, I thought others might also be having trouble and could find the list I’d compiled useful. The piece spread widely, and I was told it helped inform other people’s books coverage and syllabi. I put a list together again the following year, and so on.

But for a while, I’ve also wanted to stop. Most-anticipated books lists have wildly proliferated since 2016, as have best-of lists. And though I know how useful they can be, I’m also aware of some of the other effects they can have, especially on writers; a list like this necessarily leaves out more people than it will include. I published my second novel, Exhibit, last spring. To my surprise and alarm, though it was my second time publishing a novel, I often felt as I did the first time around: upended, exposed, as if I’d lost a layer of skin. Part of it might be that I published a book that felt, and still feels, especially vulnerable, a novel centering women hellbent on pursuing what they want, and this in a world continuing to prove that not a few people intend for women to exist as helpmeets, living for others, stripped of our rights. Regardless of the book, though, I know few writers who find publishing to be a calming experience.

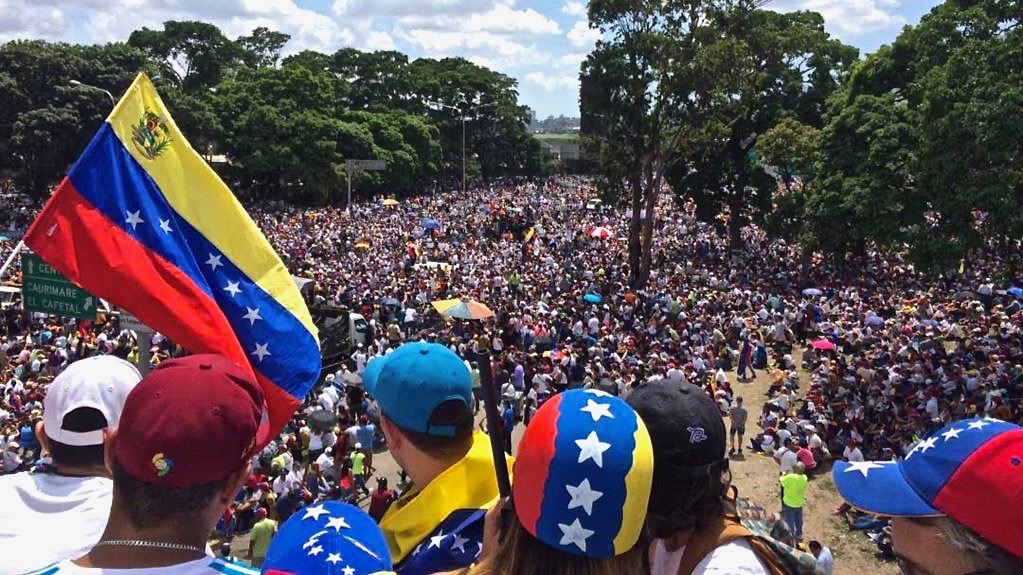

But as the writer Michelle Hart did last year with queer books, I took a look around and saw that women of color’s books are still relatively passed over and sidelined. It’s still the case that a disproportionately large majority of books released by the biggest publishers are by white writers. Book bans are still sweeping the country, and by far the books most affected are those by people of color, and by queer and trans writers. The news remains terrifying. I am tired of my anger and sorrow. I want to move toward what I love.

With all I am, I love reading. I think of writing as an extension of the reading, a kind of call and response. So, here are some of the 2025 books I am excited about. I’m one person with an incomplete knowledge of forthcoming titles. If you’re looking forward to a title not mentioned here, please consider preordering it from your local bookstore, requesting it from the library, telling people about it, or all of the above.

A few brief notes on categories: this piece is front-loaded toward the earlier part of the year, as there’s less information about later books. I love and crave poetry, but am less aware of what’s publishing in poetry, so I’ve kept this list to prose. The term “of color” is limited, dissatisfying, and shifting. In its earlier years, a couple of versions of this list included nonbinary writers. After Electric Literature and I heard from a number of nonbinary writers that it can be preferable to avoid grouping nonbinary people with women, I’ve since focused on women: cis women, trans women, and nonbinary women who assented to having their books included in this space. The majority of nonbinary writers and readers we’ve heard from have found this preferable. Electric Literature has recently published a piece about anticipated books by queer writers.

I’m elated about the novels, memoirs, essay collections, and other books coming our way; please join me in celebrating.

January

Black in Blues by Imani Perry

I’ll read anything the brilliant Imani Perry publishes, and her latest book, a meditation on the color blue and its roles in Black history and culture, is no exception. “This book is a great gift, in that it allowed me to see the world anew with Perry’s clear-eyed insight,” says Jesmyn Ward.

We Do Not Part by Han Kang, translated by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris

During a phone interview not long after learning she’d received the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, Han Kang was asked which of her books, if she had to pick one, she’d recommend to those new to her writing. Han suggested We Do Not Part, a novel haunted by the aftermath of the 1948–1949 Jeju Island uprising and massacre. Over 30,000 people on Jeju were killed by U.S.-backed Korean forces, and their ghosts fill the pages of We Do Not Part.

Good Girl by Aria Aber

One of my favorite things about having a phone is that, with some friends, I occasionally exchange photos and screenshots of poetry and excerpts we think the other will appreciate. And as I send and receive these gifts, scraps of words we’ve especially loved, Aria Aber’s poems routinely show up. Good Girl, her first novel, evokes a young Afghan German woman trying to destroy her life. Jamil Jan Kochai calls it “a heartbreaking song of youth and desire and violence and history and the unbearable solitude of displacement.”

Homeseeking by Karissa Chen

I’ve awaited Hyphen editor-in-chief Karissa Chen’s novel for a while, and it’s here at last: a 500-page epic traversing six decades in Hong Kong, Taiwan, New York, and Los Angeles. Celeste Ng says that Chen’s debut “weaves expertly between present and past, telling the story of childhood sweethearts who meet again late in life and are torn between looking back and moving on.”

The Life of Herod the Great by Zora Neale Hurston

This previously unpublished historical novel from Zora Neale Hurston examines and reimagines the infamous Biblical figure King Herod. “The Life of Herod the Great—like Hurston herself—is a masterpiece, a miracle, and a marvel,” according to Tayari Jones.

February

Death Takes Me by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated by Sarah Booker and Robin Myers

A professor stumbles upon a castrated corpse positioned beside a poetic couplet jotted in pink nail polish. More mutilated bodies follow, as do more poems, in this new novel from Pulitzer Prize-winning Cristina Rivera Garza.

Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin

Canisia Lubrin, a recipient of the Windham-Campbell Prize for Poetry, has written a first book of fiction that “departs from the infamous real-life ‘Code Noir,’ a set of historical decrees originally passed in 1685 by King Louis XIV of France defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire.” The 1686 Code had 59 articles, and Lubrin’s book includes 59 braided stories that Christina Sharpe praises for their “formal inventiveness and sheer audaciousness.” Published last year in Canada, Code Noir will soon also be available in the U.S.

Ugliness by Moshtari Hilal, translated by Elisabeth Lauffer

A book-length essay on power, attraction, and what is considered beautiful and ugly from visual artist, curator, and writer Moshtari Hilal. Melissa Febos calls Ugliness a “thoughtful, provocative, playful, and truly original exploration of bodily aesthetics and the factors that define them.”

Casualties of Truth by Lauren Francis-Sharma

An ex-McKinsey consultant named Prudence Wright and her husband go out to dinner in D.C. with a colleague who, to Prudence’s surprise, shares part of her past. “Once again, Francis-Sharma’s phenomenal prose delivers; here, with exquisite suspense in a revenge story chocked full of thorny characters,” says Xochitl Gonzalez. “This is an unforgiving tale of cat-and-mouse begging us to confront just how far we’d go to take control in a society hell-bent on minimizing our pain.” I’ve admired Lauren Francis-Sharma’s work for years.

March

Sucker Punch by Scaachi Koul

Sucker Punch is a follow-up to Scaachi Koul’s One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter, her hilarious, astute debut essay collection. This time, according to Jennette McCurdy, Koul has written “a beautiful, painful, funny, and ultimately inspiring account of a marriage crumbling.”

Liquid by Mariam Rahmani

One summer, a scholar with a Ph.D. from UCLA decides to “marry rich” and sets off on a hundred dates, aiming to have a marriage proposal by the time school starts again in the fall. Her plans change, though, after a tragedy in Tehran. Bryan Washington says that “Liquid is a dream of a book—written with heart and feeling and longing and clarity, bracingly astute, elastic, and precise—an absolute delight expanding the possibilities in American fiction.”

Luminous by Silvia Park

Three siblings—two human, and one a robot—get tangled in a murder investigation taking place in a unified Korea. Silvia Park’s rendition of a near future is their debut book, and Charles Yu calls it “a novel full of pleasures, big and small, gorgeous sentences from which Park weaves a rich, layered story of family and work, of history and speculation, of Korea, past, present and future.”

The Dream Hotel by Laila Lalami

Even our dreams are surveilled and punished in this alarmingly plausible novel by the virtuosic Laila Lalami. In The Dream Hotel, a woman is detained for months in a “retention center” because, based on an algorithmic probe of her dreams, authorities have decided she is at risk of harming her beloved husband.

The Haunting of Room 904 by Erika T. Wurth

Olivia Becente, a woman who can see and hear ghosts, uses her abilities to investigate mysterious deaths. “The Haunting of Room 904 casts a magnificent spell with a deep grief at its heart,” says Lev Grossman.

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian

Sarah Thankam Mathews praises Goddess Complex as “the most interesting, illuminating, and bold contemporary novel of ideas” she’s read in years. Sanjena Sathian’s second novel follows a woman who walked out on her husband because they couldn’t agree on whether or not to have children. Now the husband has gone missing, and the woman sets off to try to find him.

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy

In this second novel from the author of Dances, a journalist grieving his father’s death investigates a cult called “The Nameless.” Megha Majumdar describes O Sinners! as “a world where mares and wolves live alongside grief and love and memory, each its own creature, each equally dreamlike and real.”

The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji

A multigenerational chronicle of a family divided into far-flung cities: Tehran, Houston, and Los Angeles. “Sanam Mahloudji takes us on a journey to reshape our understanding of power, heritage, and ancestry—and brings a rare wisdom to the chaos of family,” says Vanessa Chan.

April

Audition by Katie Kitamura

I heard Katie Kitamura read from Audition last summer in Tennessee, and was both mesmerized and tantalized: I wanted to read the rest of it immediately. Two people meet for lunch in a New York restaurant, and as is usual with Kitamura’s remarkable oeuvre, so very much more is happening.

Flirting Lessons by Jasmine Guillory

I recommend Jasmine Guillory’s utterly delightful novels right and left, and now there’s a new one to shout about. One woman gives her friend lessons in flirting, and what ensues between them is something more than friendship. Taylor Jenkins Reid says, “This is Jasmine Guillory at her best. She has outdone herself.”

When the Harvest Comes by Denne Michele Norris

At the reception for one man’s wedding to another, he learns that his estranged father, a reverend, has just been in a terrible car accident. When the Harvest Comes is a debut novel from Denne Michele Norris, editor-in-chief of this magazine, and Alejandro Varela says the novel is “for anyone who’s ever believed they didn’t deserve happiness, for anyone whose worldview has been shaped by marginalization, for anyone who’s accomplished more than was expected of them.”

Searches by Vauhini Vara

Vauhini’s Vara published a Believer essay in 2021, “Ghosts,” involving her sister’s death, AI, and some of the outer borders of language. I have read it so often; each time I reread it, I get full-body chills all over again. Searches is the formidable Vara’s first essay collection, and it includes “Ghosts” as well as a number of Vara’s other essays on technology and humanity.

The Hollow Half by Sarah Aziza

A debut memoir about disordered eating, ghostly dreams, and ancestral voices, written by a daughter and granddaughter of Palestinian refugees. According to Alexander Chee, “Sarah Aziza’s astonishing memoir is a record of a mystery of the self, a woman in the grip of a despair that has too many names or none at all, hiding as it seeks to erase her. To survive she must move towards being, as she says, ‘ambushed by hope.’”

Authority by Andrea Long Chu

Acclaimed critic Andrea Long Chu’s first book brings together her writing on novels, television, theater, and video games. Authority is described as “a bold, provocative collection of essays on one of the most urgent questions of our time: What is authority when everyone has an opinion on everything?”

Medicine River by Mary Annette Pember

“I have never read a book that has changed me so profoundly,” says Javier Zamora. Mary Annette Pember, a former president of the Native American Journalists’ Association, examines histories of Native boarding schools in the U.S.

Bad Influence by Claire Ahn

A young fashion influencer striving to financially support her family finds it difficult to both uphold her values and meet the demands of her professional life. I initially heard about Bad Influence from Claire Ahn last summer, and have anticipated it since.

Zeal by Morgan Jerkins

Morgan Jerkins’s new novel, extending across a hundred and fifty years, asks if there can be reconciliation in the future for what was broken in the past—not just for the people living in the future, but also for the dead. Kiese Laymon says, “If ever there was a time for textured art that takes the complicated, often comically ironic, intoxicating love lives of the enslaved serious, it is now. It is Zeal. Morgan Jerkins made it. We can rejoice.”

May

The Book of Records by Madeleine Thien

Madeleine Thien’s novel takes place at an enclave, “a staging-post between migrations,” where people from the past and future overlap. Lina, who’s come to the enclave with her father, befriends great thinkers including Jupiter, a Tang Dynasty poet; Bento, a seventeenth-century Jewish scholar from Amsterdam; and Blucher, a 1930s philosopher fleeing Nazi persecution.

The Original Daughter by Jemimah Wei

Living with her parents and grandmother in a one-bedroom apartment in Singapore, roiling with ambition, Genevieve Yang believes herself to be an only child. But then, an unexpected sibling shows up. I’ve deeply loved Jemimah Wei’s writing and mind; Roxane Gay lauds the The Original Daughter as “an incredible debut.”

Awake in the Floating City by Susanna Kwan

A stalled artist lives with a hundred-and-thirty-year-old woman in a deserted San Francisco, the city flooded by years of rain. Neither wishes to leave; so they stay, and talk. “Awake in the Floating City is an astonishing work of art, rich with attention, patience, and love: the rare elegy that hums with hope, and makes the strongest case I’ve ever read for remembering the people and places that matter to us,” says Rachel Khong.

So Many Stars by Caro de Robertis

Caro de Robertis conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with trans, nonbinary, genderqueer and two-spirit elders of color, gathering conversations they wove together into a “collective coming-of-age story.” Jaquira Díaz calls So Many Stars “an intimate and multilayered accounting of personal and collective grief, family, love, art, and the complexities, joys, and heartbreaks of the past and present.”

The Wanderer’s Curse by Jennifer Hope Choi

Jennifer Hope Choi’s mother tells her they both share the curse of yeokmasal, said to cause the afflicted person to wander far from home. Choi, an editor at Bon Appétit, relates a story of drifting apart from her mother and coming back to her again.

The Lost Queen by Aimee Phan

I delight in Aimee Phan’s writing, and in The Lost Queen, her first book since 2012, a fortuneteller’s granddaughter begins having visions of her own. She and a friend take on other abilities—telepathic, premonitory, and linguistic—they’ll need for difficult times ahead.

June

I’ll Tell You When I’m Home by Hala Alyan

On days when Hala Alyan has published a new poem or essay, I’m inclined to drop what I’m doing to read her splendid writing. I’ll Tell You When I’m Home is Alyan’s debut memoir: after years of miscarriages, Hala Alyan seeks out motherhood via surrogacy. In this time of delayed hope, Alyan turns to “the archetype of the waiting woman,” Scheherazade, and gathers family stories and communal myths from Palestine, Kuwait, Syria, Lebanon, the Midwest, and elsewhere.

Flashlight by Susan Choi

A new Susan Choi book! I’m a completist about Choi’s singular fiction, and Flashlight is described as a novel “tracing a father’s disappearance across time, nations, and memory,” his daughter trying to learn more about the man she lost.

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley

From the author of the memorable Nightcrawling comes a novel centered on a group of teenage mothers in small-town Florida. According to Kaitlyn Greenidge, Leila Mottley “brings to life the beauty and brutality of the Florida panhandle, and turns narratives about motherhood, girlhood and the South on their heads.”

Clam Down by Anelise Chen

In this intriguing memoir, Anelise Chen is mourning a divorce when she’s “transformed into a ‘clam’ via typo after her mother keeps texting her to ‘clam down.’” With that typo-driven metamorphosis alone, I was already beguiled—bugled—ahem. “From the moment I started reading it, I could hardly put it down—carrying it around like a talisman, crawling inside it like a wunderkammer, putting my ear to it like a shell, so I could hear its vast, surprising ocean,” says Leslie Jamison.

July

The Other Wife by Jackie Thomas-Kennedy

I’ve followed Jackie Thomas-Kennedy’s work since I first read striking stories she published in literary magazines. The Other Wife, her first novel, chronicles the shifting desires of a woman in her late thirties who’s not sure she’s made the right life choices.

Hot Girls with Balls by Benedict Nguyễn

A joyfully hailed satire about trans star athletes—indoor volleyball players—from dancer, producer, and novelist Benedict Nguyễn. Patrick Cottrell calls it “a rigorous and gutting satire, a courageous social fantasy, a realistic portrait of the hell that is humanity, a deeply felt book about love and competition.”

Necessary Fiction by Eloghosa Osunde

The Plimpton Prize-winning author of Vagabonds! has written an exploration of cross-generational queer life in Lagos. Necessary Fiction is described as a novel posing questions such as: “What makes a family? How is it defined and by whom? Is freedom for everyone?”

August & later

The Grand Paloma Resort by Cleyvis Natera

A famous resort in the Dominican Republic is at the heart of this second novel from Cleyvis Natera. Central characters include Vida, a curandera called to the resort to help with a crisis; Laura, a resort manager; Laura’s sister Elena, who babysits at the resort; and Elena’s child’s father, who bribes Elena for help she shouldn’t give.

Dust Settles North by Deena ElGenaidi

I’ve kept an eye out for Deena ElGenaidi’s short-form writing for a while, and we’ll soon have her first novel, Dust Settles North. ElGenaidi, a former editor at Hyperallergic, begins her novel with two siblings flying from New York to Cairo for their mother’s burial.

The Wilderness by Angela Flournoy

“The Wilderness is a wonderfully ambitious novel that follows five women throughout decades of friendship, as they struggle to find purpose and belonging in their rapidly gentrifying cities,” says Brit Bennett. The many fans of The Turner House will rejoice to have a second book from Angela Flournoy.

Trigger Warning by Jacinda Townsend

Jacinda Townsend’s third novel is told in alternating sections by Ruth Hurley, who changes her identity and moves after her father is killed by police, and Myron Hurley, her husband, who’s trying to learn the truth about his wife.

Tree Dreaming by Brenda Lozano, translated by Heather Cleary

A kaleidoscopic examination of the kidnapping of a two-year-old girl in 1940s Mexico City. Like Townsend’s, Lozano’s novel also alternates perspectives, though Tree Dreaming switches between the perspectives of the family of the kidnapped child and of the kidnappers raising the girl.

What a Time to be Alive by Jade Chang

Jade Chang’s first, riotous novel was unforgettable, and What a Time to be Alive is her follow-up, featuring a grieving woman who becomes an influential self-help guru.

Carnaval Fever by Yuliana Ortiz Ruano, translated by Madeleine Arnivar

The winner of an English PEN Presents Award, Carnaval Fever is set in Ecuador and involves a young girl who’s also “simultaneously the body of all the women who’ve raised her.”

The White Hot by Quiara Alegría Hudes

A furious mother leaves her house in the middle of a family argument, goes to the bus station, and asks for a ticket to the furthest destination. She ends up leaving for ten years, and the novel takes the form of a letter from the mother to her daughter about this time.

This is the Only Kingdom by Jaquira Díaz

Described as “an epic portrayal of a working-class Puerto Rican family that spans generations,” and taking place in the aftermath of a murder in Humacao, This is the Only Kingdom is Jaquira Díaz’s second book and debut novel. I first heard Díaz read from her writing last year, an experience that made me an admirer for life.