I grew up watching fights with my father on television, and have always been drawn to the sport—its characters, its rhetoric and, later, the best writing about it by stylists like Hugh McIlvanney, who once wrote of the terminally shy, matchstick-thin, Welsh fighter Johnny Owen, who died in the ring: “It is his tragedy that he found himself articulate in such a dangerous language.” This quest for articulation is part of the appeal of boxing for me, the way its fighters attempt to give meaning to months of training, and the vicarious sort of absorption the spectacle holds for its audience. It is also full of extraordinary people, often drawn from the fringes—socially, economically and emotionally—knocking themselves out to be like everybody else, as Saul Bellow once said of John Berryman.

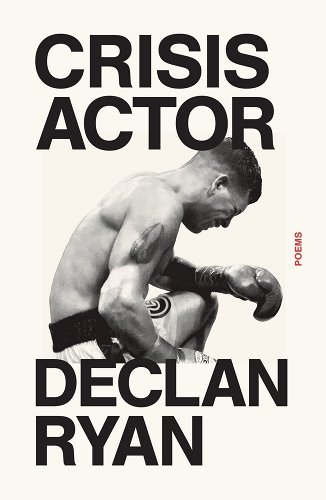

In my first collection, Crisis Actor, I have a sequence of poems on and about boxers, and this was in part a way of trying to get in some of the curt, at times deluded, things they have said about themselves and about their trade, but also as a way of trying to find some corner of modern life that wasn’t given over to evasion, or mediated through layers of deflection and distraction. Those fighters I wrote about could be grandiose, braggadocious and—at times—woundingly romantic about each other, and their sport. The books below aren’t the grand pillars of boxing writing—there’s no Mailer, Hemingway or London here, but rather they’re more recent, but no less nuanced or muti-layered, works which take boxing as their entry-point but go off in all sorts of directions to tell stories of loyalty, corruption, greed, luck and endurance. They too are articulate in—and about—that dangerous language, the fight game.

Boxing: A Cultural History by Kasia Boddy

Kasia Boddy is a Professor of American Literature at Cambridge University and this is an impressively intertextual, beautifully illustrated and expansive survey of responses to ‘the sweet science’ across a range of artforms. Its historical scope takes the reader back to the Ancients, and forward to the era of the heavyweight giants of Ali, Frazier et al; via the paintings of George Bellows and the prose of Philip Roth. The imprint of boxing, and its legendary figures, in music and film are perceptively discussed—the emphasis mostly on reception, rather than the participants’ own testimonies, but the scale, range and insight justify its editorial focus turning away from those inside the ring onto the interested, creative, audience on the safe side of the ropes.

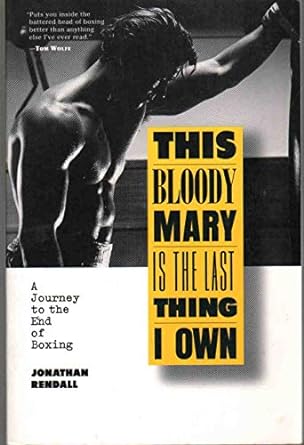

This Bloody Mary is the Last Thing I Own by Jonathan Rendall

Rendall was many things: a journalist, a gambler, a novelist and—for a time—a manager/advisor to the British boxer Colin ‘Sweet C’ McMillan, during which period he was able to guide his fighter towards a world title. This book is part memoir, part survivor’s testimony, to the boxing business of the early 1990s—taking in field trips to Vegas, seeming wild goose chases to Cuba and plenty of ominous characters cornering the out of his depth Rendall in dark rooms. Beautifully written, witty and prone to tall tales, Damon Runyon was an influence on Rendall’s approach to ‘the facts’ as much as his journalism background. This is a riot and—additionally—a lyrical insight into the nature of luck, good and bad, which is as much a part of boxing as it is the gamblers’ constant companion.

A Man’s World: The Double Life of Emile Griffith by Donald McRae

McRae is a giant in the modern boxing writing game, for his integrity as an investigative journalist as much as his ability to craft narratives from this often incredulity-baiting sport. His biography of Emile Griffith is an example of his diligence and sensitivity, too—taking the story of a boxer from the Virgin Islands who—as a fighter – was a regular fan favourite at Madison Square Garden in the 60s, but whose private life often took in New York’s gay scene. He killed an opponent—Benny Paret—in the ring, following homophobic taunts at the weigh in and, heartbreakingly, said later in life “I kill a man and most people forgive me. However, I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

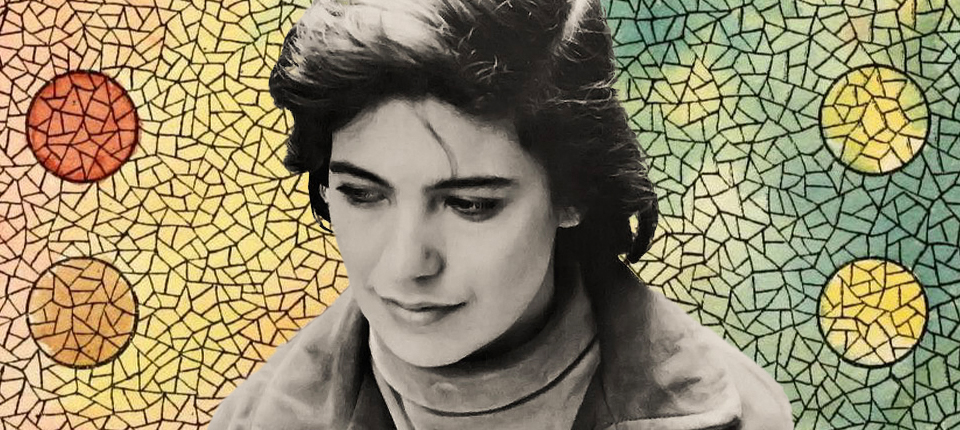

On Boxing by Joyce Carol Oates

Oates was an observer of fights at ringside from a young age, attending shows with her father, and as such she brings an attuned ear to her writing about the characters, and ceremonies, which take place within it. She’s especially good on the physicality—not only of the fighters themselves, but on the action of being a witness to such apparent barbarism at first hand: it’s acutely the case that watching in person is a markedly different experience to the flattened spectacle on television; the exposure at close range, and the sounds of blows being absorbed. As one would expect, she gets to the root of boxing’s primal appeal, but is—like so many of the best writers about it—undeceived, unsentimental and often conflicted about the damage it creates, on participant and spectator.

The Years of the Locust by Jon Hotten

If this had been written as fiction its editors would have been pilloried for allowing such absurdity into print. Rick ‘Elvis’ Parker—a discount store Don King—embodied much of the worst of boxing’s underbelly: a lying, corrupt fantasist who swindled and connived. One of his ‘charges’, Tim Anderson, the man who would be king (or at least next heavyweight champion of the world) sees his semi-promising career disappearing into a realm of fixed fights and ever-decreasing circles, until the pressure —and the poison—he’s exposed to leads him to commit murder. As lurid and compelling as some of the strip-lit venues it takes in, this is hard evidence of why boxing has been referred to as ‘the red-light district of sport’.

Born to Box: The Extraordinary Story of Nipper Pat Daly by Alex Daley

Daley’s grandfather Pat ‘Nipper’ Daly was an astonishing boxing prodigy, a ‘Wonderboy’, fighting grown men while still a young teenager throughout the 1920s, displaying astonishing skill and grit having made his professional debut at the staggeringly young age of 9 or 10. This biography is based on extensive—and committed—research and exposes the treatment Daly endured at the hands of management, and the boxing business, which meant he was effectively ‘washed up’ by the age of 16, robbed of his prime by continually boiling down to make a weight his growing frame couldn’t possibly remain at. A slice of social history, as well as one of the more remarkable narratives to emerge from British rings, this is a story from the scarcely believable frontiers of sport.

Boxer Handsome by Anna Whitwham

Whitwham’s debut novel brings to life the amateur gyms and the tribal rivalries of East London, while highlighting that enduring paradox of boxing: that often the ring is one of the only places where its combatants feel safe, or in control, away from the chaos of life outside its regulated borders. Written with a touch of Denis Johnson’s terse lyricism, Whitwham’s book is—in part—inspired by her grandfather’s youth in East-End gyms, and his time as an amateur boxer who once shared a bill with Jack Dempsey. She has since learned to box herself and is working on a non-fiction book about her immersion in boxing as a participant, rather than an interested observer.

Dog Rounds by Elliot Worsell

Elliot Worsell is an excellent writer who happens to—largely—cover boxing, and his Dog Rounds is a difficult, candid and often conflicted investigation of fighters who have killed, or seriously injured, their opponents in the ring. As well as being open about his reservations around continuing to watch – and chronicle—the sport, Worsell is sharp on the limited options facing haunted fighters who have little choice but to continue their careers even after the worst possible outcome, with no other way of earning a living. His visit to watch Mexican wrestling is an especial highlight, its cartoonish, pantomime display a reminder that, for all his ethical wrangling, he is impossibly drawn to fights which have meaning, even if they can bring with them dire consequences.

Sporting Blood: Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing by Carlos Acevedo

Acevedo is one of the most talented boxing writers working today and this is a book in the lineage—and spirit—of some of the great boxing compendia, McIlvanney on Boxing, or A.J Liebling’s round-ups. Acevedo’s choice of subject, as well as his mix of expertise and knack for character dissection, makes him compelling company in these essays about—often forgotten, or at least marginal—fighters. He is especially drawn to the tragic, the unseemly, and the backwards-facing sides of the sport. Despite shining a light into dark places his is not a spirit of relishing, but rather an attempt to get to the root cause of these often desperate, cornered and self-annihilating figures, as well as those who sought to benefit from their gifts while keeping their own hands clean.

Not Without A Fight by Ramla Ali

Ali embodies many of the cliches which get wheeled out by boxing’s most vocally enthusiastic apologists—the epitome of someone whose life was turned around if not by, then at least within, the strictures of a gymnasium, and later under the bright lights. A Somali refugee to England, Ali has worked her way towards being one of the brightest prospects in the female code, not to mention a model and humanitarian, and this is a mix of memoir and motivating treatise, as well as the only example here from an active participant in the sport, rather than a witness to it. Ali has since lost her unbeaten record, avenged the loss, and is rebuilding towards a run at a world title.