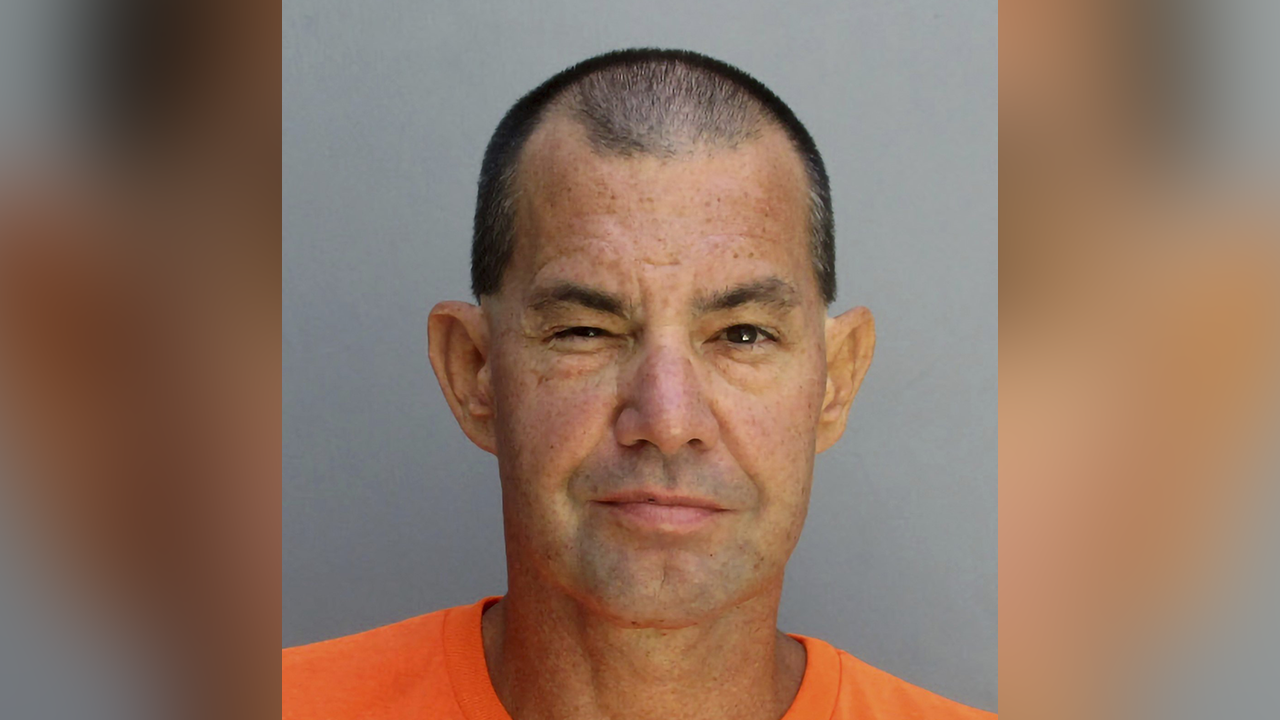

John Bailey, the cinematographer on Ordinary People, Groundhog Day, As Good as It Gets and dozens of other notable films who endured two “stressful” terms as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, died Friday. He was 81.

Bailey died in Los Angeles, his wife, Oscar-nominated film editor Carol Littleton (E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial), announced.

”It is with deep sadness I share with you that my best friend and husband, John Bailey, passed away peacefully in his sleep early this morning,” she said in a statement. “During John’s illness, we reminisced how we met 60 years ago and were married for 51 of those years. We shared a wonderful life of adventure in film and made many long-lasting friendships along the way. John will forever live in my heart.”

They worked on more than a dozen features together.

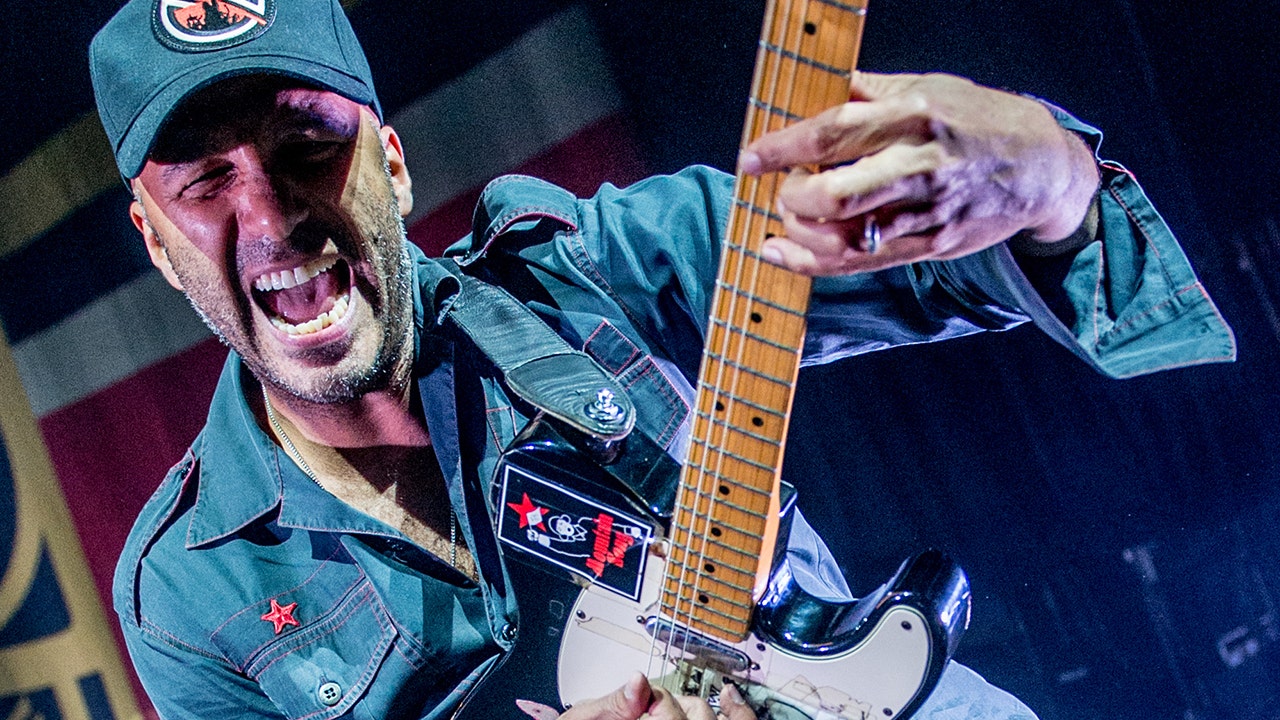

The Southern California-raised Bailey served as the director of photography for director Paul Schrader on American Gigolo (1980), Cat People (1982), Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), Light of Day (1987) and Forever Mine (1999) and collaborated with Lawrence Kasdan on The Big Chill (1983), Silverado (1985), The Accidental Tourist (1988) and Wyatt Earp (1994).

He had another fruitful relationship with director Ken Kwapis, working with him on six films: Vibes (1988), The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants (2005), License to Wed (2007), He’s Just Not That Into You (2009), Big Miracle (2012) and A Walk in the Woods (2015), where he reunited with Ordinary People director Robert Redford.

Bailey also shot Michael Apted’s Continental Divide (1981), Stuart Rosenberg’s The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984), Wolfgang Petersen’s In the Line of Fire (1993), Robert Benton’s Nobody’s Fool (1994), Sam Raimi’s For Love of the Game (1999) and Callie Khouri’s Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood (2002).

In a 2020 interview for American Cinematographer magazine, Bailey said his philosophy was “imbued with an international perspective” — one of his touchstone movies was the Vittorio Storaro-shot The Conformist (1970) — and that he had “a singular focus on the kinds of films I wanted to make, even from the time I was an assistant and [camera] operator.”

“I did not want to do tawdry films,” he added. “I did not want to do exploitive films or violent ones. I really held out, sometimes at great personal expense, literally, in terms of money, to do films that I knew were building a résumé that when I did become a director of photography, that was part of who I was.”

A member of the American Society of Cinematographers since 1985, he received a lifetime achievement award from the group in 2015.

John Bailey (right) with director Lawrence Kasdan on the set of 1983’s ‘The Big Chill’

Bailey also was a longtime board member at the Academy when he followed Cheryl Boone Isaacs as AMPAS president in August 2017, becoming the only one to come from the cinematography branch. He won reelection the next summer before being succeeded by David Rubin in August 2019.

His tenure was marked by a huge increase in members, especially for international and non-Hollywood folks; the ousters of Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby and Roman Polanski from the Academy; a Kevin Hart hosting imbroglio; and three moves meant to boost Oscar TV ratings that were torpedoed amid great criticism: the creation of a “popular Oscar,” the elimination of three live best song performances on the show, and the sidelining of four winners’ speeches to commercial breaks.

“I had no idea how stressful that job was going to be,” he said.

The son of a machinist, John Ira Bailey was born on Aug. 10, 1942, in Moberly, Missouri, and raised in Norwalk, California. He edited the school newspaper at Pius X High School in Downey, California, then attended Santa Clara University and Loyola Marymount University, graduating in 1964.

He decided to pursue cinematography while spending two years at USC in a new graduate program for film studies.

Bailey spent more than a decade as an apprentice cinematographer/camera operator for the likes of Néstor Almendros, Vilmos Zsigmond and Charles Rosher Jr. on such films as Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1976) and Robert Altman’s The Late Show and 3 Women, both released in 1977.

The first studio feature he shot as D.P. was Boulevard Nights (1979), directed by Michael Pressman.

Bailey broke through when two films he worked on back-to-back — the stylish neo-noir American Gigolo, just the third film that Schrader directed, and the restrained Oscar best picture winner Ordinary People, Redford’s directorial debut — were released within seven months of each other in 1980.

Boulevard Nights producer Tony Bill had recommended Bailey to Redford. “Not that many first-time directors back then would have hired an inexperienced cinematographer,” Bailey said in 2015 on an ASC podcast, “but Redford certainly had the experience and the confidence [from his years as an actor] to do that.”

For Bailey, the script was always paramount when it came to taking a job, and he had great screenplays to work with on Groundhog Day (1993), co-written by director Harold Ramis, and the best picture Oscar nominee As Good as It Gets (1997), co-written by director James L. Brooks.

His cinematography résumé also included Honky Tonk Freeway (1981), That Championship Season (1982), Without a Trace (1983), Racing With the Moon (1984), Brighton Beach Memoirs (1986), Swimming to Cambodia (1987), My Blue Heaven (1990), Extreme Measures (1996), Living Out Loud (1998), The Anniversary Party (2001), How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003), The Producers (2005) and The Way Way Back (2013).

Bailey also directed a handful of films, including Lily Tomlin’s The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe (1991), China Moon (1994), Mariette in Ecstasy (1996) and Via Dolorosa (2000).

Bailey said he sought the Academy presidency primarily to support the organization’s film archive, the Margaret Herrick Library, the Nicholl screenwriting programs and international cinema. “I didn’t want to worry about the Oscars so much,” he said in 2021. “The studios are invested in the Oscars, the studios are going to make sure the Oscars take care of themselves, one way or another.

“Everybody seems to have an idea — and they think their idea is best — about what the Academy Awards should be. The absolute inanity, coupled with the hubris that comes with it sometimes, especially on the part of certain trade and media critics … it just really bothered me that whole Oscar season, day after day, having to read the drivel by some of these journalists that said they knew how to fix the Oscars.”

He and Littleton, who is to receive an honorary Oscar at the delayed Governors Awards in January, had no children.

“All of us at the Academy are deeply saddened to learn of John’s passing,” Academy CEO Bill Kramer and Academy president Janet Yang said in a joint statement. “John was a passionately engaged member of the Academy and the film community. He served as our president and as an Academy governor for many years and played a leadership role on the cinematographers branch. His impact and contributions to the film community will forever be remembered. Our thoughts and support are with Carol at this time.”

Donations in his memory can be made to the Academy Foundation.

Bailey said his formative years in Hollywood taught him that becoming a successful cinematographer had more to do with just learning how to operate the equipment.

“It’s about learning how people work together, forging relationships, dealing with the stresses and the sort of unexpected accidents and gifts that you’re given day to day and developing a perspective that when you go to work in the morning, you’re not executing a blueprint based on storyboards or discussions or anything,” he said. “You are in a living, changing, spontaneous, human flux. Anything can happen at any given moment.”