Lauren Palmer was 15 years old when she set out on a seven-night Nickelodeon cruise of the Mexican Riviera. This was 2009, the apex of popularity for the actress’ teen sitcom True Jackson, VP, and the only condition placed on an all-inclusive vacation for her entire family was that she spend a few hours signing autographs on the lido deck. She’d been looking forward to the break. But as the ship drifted from Los Angeles to Puerto Vallarta, its young passengers mainlining sugar and getting slimed in the branded photo booths, Palmer rarely strayed from her cabin. “I felt like I was walking around in a SpongeBob suit that I couldn’t take off,” she says. “I was trapped. I couldn’t leave my room without someone coming up to me calling me ‘True Jackson.’ What you are, to everyone, is just a character … just part of their experience.”

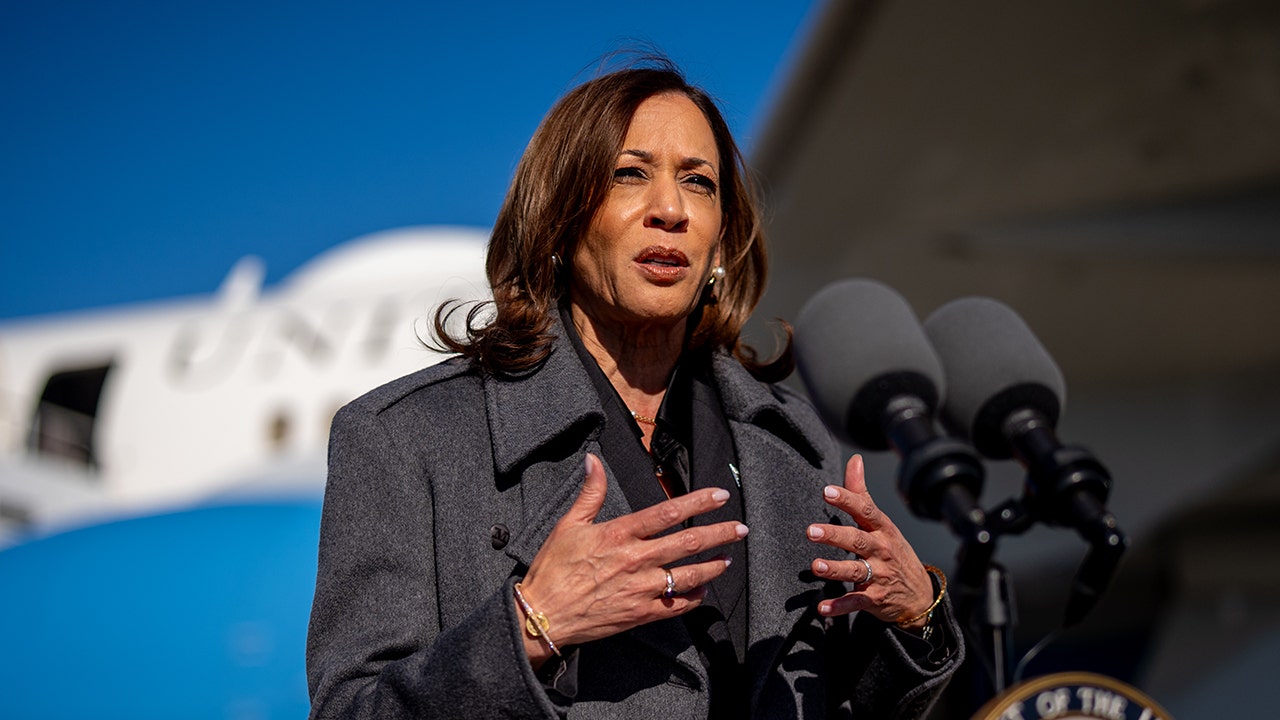

Photographed By Munachi Osegbu

Little evidence of the voyage survives online, save one YouTube clip of Palmer recapping a day’s excursion to Mazatlán from her balcony. The young performer sells it with a smile, but she’s holding up a copy of J-14 magazine, the teenybopper bible, as if she’s filming a proof-of-life video. Recalling that formative week over brunch, more than a decade later, she says she eventually fainted from anxiety. Epiphanies rarely come so early in life, but Palmer operates on her own schedule. She’d lost a Screen Actors Guild Award to Glenn Close and stolen scenes from Angela Bassett and Laurence Fishburne before most kids her age had parted with the last of their baby teeth. So, by the time the child-star era of her life came to its natural conclusion — True Jackson, VP ended in 2011, the same week she celebrated her 18th birthday — Palmer had long vowed that the only character she’d be known for in the future would be one of her own design.

Keke Palmer — the name is a derivative of her middle name, Keyana — is a creation, one that Lauren Palmer has been honing her entire career. The actress, singer and producer says as much in the launch video for her startup, a digital platform called KeyTV. In it, she makes the duality literal, appearing as two different people: Lauren in a beige dress and Keke hamming it up in a sequined jacket. It’s Keke who aggressively courts 11.5 million Instagram followers with daily hits of comedy. Keke’s the one whose flamboyant gesticulation and charismatic storytelling style are sought after by talk show bookers. As for Palmer’s career-shifting performance this summer in Jordan Peele’s $171 million-grossing sci-fi satire, Nope, there’s some Keke there, too. Neither alter egos nor fabrications, the twin identities are merely a distinction Palmer has made to survive and, as evidenced by the year she’s had, thrive in the entertainment industry. “I’m a quirky artist, but I’m an artist, and it’s important for people to understand that Keke is just a part of who I am,” she says. “It’s been a winding road of trying to figure out how to do what I love but also exist outside of this caricature.”

Says Peele, “Keke developed this relationship, especially with the Black community, as being a member of our family — and being the hardest-working member of that family. I think the world is catching up to how capable she is. I’ve been doing this for a little bit now, and I haven’t met another like her.”

Palmer does not entertain comparisons, and her actions defy them. Where others use digital platforms as a launchpad, Palmer wielded hers like a boomerang — perfecting a confessional style of comedy that prompted a career resurgence as she aged out of kid roles and became an adult. While many stars nurture entrepreneurial aspirations with eyes on an IPO, Palmer is bankrolling KeyTV with her own money in hopes of creating opportunities behind the camera and below the line for people from historically marginalized communities, without access to the traditional Hollywood pipeline. And, sure, she realizes that Nope has unlocked new doors — she’ll host Saturday Night Live for the first time on Dec. 3 — but she’s not counting on anyone but herself to turn the knob. “I think people always sleep on you,” she says, eyes playfully darting in either direction, as if someone is underestimating her at this very moment. “If you don’t at least worry about that, you’re in trouble.”

***

Palmer appears relaxed when she arrives at a restaurant not far from her Studio City home on a mild Sunday morning. She takes her seat on a banquette in the garden patio that, like so many Los Angeles venues, is one block too close to a freeway to maintain its intended bucolic illusion. But the hot chicken and biscuits are solid, and the artificial foliage offers some privacy.

Hair pulled back, free of makeup, thick-framed turquoise glasses pulling attention to her eyes, and wearing a pink sweatsuit, Palmer is as close as she likely gets to incognito. But even in civvies, she is unmistakably herself. The volume of her voice rises and falls along with her interest in the conversation. She drops one of her preferred figures of speech (“That’s the gag!”), collapses on the cushions in feigned shock at a question — “I’m on the floor right now,” she cries out — and, whether she realizes it or not, Palmer is suddenly quite conspicuous.

Photographed By Munachi Osegbu; Michael Kors jacket, Simone Rocha dress and socks, Sophia Webster shoes.

“Excuse me, you’re Keke Palmer,” says the first woman to notice, leaning over from the nearest table. “I recognized your voice from the Call Her Daddy podcast. Great episode.”

“I love you,” a less subtle diner shares moments later, quickly pivoting from compliment to professional overture. “I would love to bang you out, girl,” she announces, slipping Palmer a piece of paper. “I’d give you a real good beat.”

It’s a business card, Palmer clarifies, for a makeup artist. (The language of beauty, it seems, is also one of violence.) She remains unfazed by all this. Now 29, Palmer says she’s mostly at peace with the attention she courts — acknowledging it as part of the job. But she’s sometimes still confused by the ways these exchanges go down. “A couple of weeks ago, I was in Arizona with my boyfriend and his dad for an Eagles game,” she says, the table again cleared of admirers. “We ended up at a Dave & Buster’s and somebody was like, ‘What are you doing here?’ Same reason as you, dude! Playing games and winning tickets. Where else do you expect me to do that?”

There’s a vigilance to the way many former child stars, particularly those lucky enough to reach the other side as grounded as Palmer, navigate fame. Like an ambivalent Santa Claus, equally happy to hand out gifts or kick coal in your face, fame is always watching, always taking notes. Palmer’s approachability is owed in some part to the fact that she barely had a life before she had a career. Their daughter showing an affection and aptitude for acting, Palmer’s parents moved her and her three siblings from the Chicago suburbs to Los Angeles when she was 10 years old. She quickly accrued credits. Her SAG Award-nominated performance in the TV movie The Wool Cap was followed by a role in Madea’s Family Reunion and her real breakout, 2006’s Akeelah and the Bee. The feel-good drama starred Bassett, Fishburne and Palmer as the titular girl competing in the Scripps National Spelling Bee and led to an obligatory Disney Channel movie (Jump In) and Nickelodeon’s True Jackson, VP — in which Palmer played a high school student who moonlighted as a fashion executive.

Lions Gate/Courtesy Everett Collection

Success proved isolating, as both she and her family struggled to adjust to her new status as a breadwinner. The creeping feeling of loneliness was compounded by what Palmer describes as a strict upbringing. She now recognizes her parents’ oversight as an awareness of the razor’s edge she unknowingly walked for so many years. Running through some of the pitfalls that she managed to avoid, Palmer references a friend who recently got out of rehab for heroin — a drug she says he was introduced to on sets at a young age.

“This child-star storyline … we done heard it, it’s been beat over the head,” she says. “But for the people who think that a normal childhood is overrated, nothing’s overrated if you didn’t have it.”

Hilary Gayle/Fox/courtesy Everett Collection

***

Nope turned out to be one of those cosmic, full-circle moments. Palmer credits a 2013 cameo on Peele’s breakout Comedy Central sketch show, Key & Peele — in which she played the “anger translator” to first daughter Malia Obama — as a catalyst for her comedy career. Making up bits for Instagram and YouTube, Palmer recast herself as the lively narrator of her own story — a fourth-wall breaker who demystified her fame even as she bolstered it. This sense of humor created multiple avenues of opportunity.

“It’s very hard for most people to be themselves on TV,” says Michael Strahan, the NFL player turned broadcasting golden boy who worked with Palmer and Sara Haines on a Good Morning America spinoff, GMA3. “Keke is one of those rare ones who can be herself on camera, without any reservations, and then go on a set and be something completely different.”

Lorene Scafaria, the screenwriter and director of Hustlers, had her heart set on casting Palmer in the 2019 ensemble feature after watching the actress utterly charm Conan O’Brien and Norm Macdonald on the former’s TBS talk show. “I don’t even think her character was that funny on page,” says Scafaria, “but the best lines in the movie are the ones Keke wrote on the fly, improvising in the moment. She’s so good at that, so good at performing, because she’s always listening — always aware.”

That Palmer shared scenes with Jennifer Lopez in a blockbuster with major awards buzz the same year she accepted a full-time position on GMA3 says a lot about her appetite. And there’s a world in which she’d still be doing a daily TV job, had the pandemic not sidelined the hour. It was also the pandemic that inspired Peele, on a hot streak with Get Out and Us, to write a script that would draw audiences back to theaters — one he penned with Palmer in mind.

Barbara Nitke/STX Entertainment/Courtesy Everett Collection

“She wields the internet, yet it was my feeling that she’d not been given the role of my dreams for her,” says the filmmaker, who speaks about Palmer as much as a fan as a collaborator. In Nope, Palmer plays Emerald Haywood, the reluctant scion of a struggling Hollywood horse-training company. The ebullient character, who fills the silences left by her taciturn brother (Daniel Kaluuya), is introduced on a set and immediately enlivens it, ingratiating herself with a crew. She is both the heart of the film and its comic relief. To hear others talk about making the film, Palmer was similarly disarming on the shoot. “A director’s job is to take care of their actors,” adds Peele. “Keke’s an actor that took care of me, took care of everyone.”

Palmer says of the experience, “People don’t realize what it took to even get to the point where I could play that part. Nobody would have seen me playing that role if it hadn’t been for all the things that I’d done prior, so I’m proud of it for more reasons than one.”

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

That pride has had to endure a few unexpected swipes. In late July, with Nope comfortably No. 1 at the domestic box office, Palmer was alerted to a Twitter thread comparing her career to that of Zendaya. Both are Black women in their 20s who started acting very young, but the user attributed her perceived difference in the recognition of their accomplishments to colorism — namely that Palmer had less “mainstream popularity” than Zendaya on the grounds that the latter has fairer skin. Palmer held her tongue for about 24 hours before shutting down the conversation.

“What I wanted people to understand is that comparing me to someone solely based off of our complexions is colorism,” she says. “There are very real scenarios of colorism, racism and sexism. You don’t need to make them up. And I don’t want these little Black girls to be out there thinking they’ll never be enough, especially in their community’s eyes.”

Palmer discusses identity with ease, albeit within established guardrails. She speaks frankly about sex and sexuality — “Fuck gender,” she says after taking a sip of water. “I just want to be able to exist and not be challenged on how I’m existing” — but demurs when asked if she and her boyfriend share a home. (They share custody of a cat named Jackie Brown, which is all you need to know.)

Such specifics of her personal life seem saved for Lauren, the girl from Illinois who decided to redefine her relationship with fame after going on a crappy cruise. Palmer realizes the Lauren/Keke distinction might be confusing for some, which is why she attempted to clarify it in that video. “I’m just saying that I’m not like that all the time,” she explains. “I’ve taken those flamboyant and interesting aspects of myself and learned how to use them in a space that has become a career for me. I’m Walt Disney. That’s Mickey Mouse.”

The morning now the afternoon, Palmer gathers herself to meet her mother in front of the restaurant. She’s been waiting outside, parked in a conservative sedan. But before she departs, Palmer first considers her two names and which one she’d most like to be remembered as. She makes a serious face before a cock of her eyebrow signals a dip back into character. “Keke,” she says. “That’s the name the world wanted. So, that’s what they got.”

This story first appeared in the Nov. 16 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

![[PHOTOS] ‘Call the Midwife’ Helen George Returns In Time for Season 12 [PHOTOS] ‘Call the Midwife’ Helen George Returns In Time for Season 12](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Call-the-Midwife-Trixie-returns.jpg?w=620)