Like most journalists behind the camera, Margaret Moth was never a household name or face, despite working for CNN in war zones around the world for two decades. No viewer would have guessed, as Lucy Lawless reveals in Never Look Away, that Moth’s dramatic appearance matched the tumultuous events of her life. She had heavy, Goth eyeliner and spiky jet black hair, and multiple lovers wherever she went. As a cameraperson in the early 1990s, she covered wars from the Persian Gulf to Tbilisi, Georgia. A montage in the opening credit sequence shows just how violent that was, in scenes full of explosions and terrified civilians running down the streets. In 1992, she was shot by a sniper in Sarajevo, losing part of her jaw, yet she recovered and went on reporting almost until she died of cancer in 2010.

But for all the fireworks Moth lived through, Never Look Away is more a generic tribute to a fearless correspondent than a satisfying portrait of a uniquely troubled individual. “I never fully understood what was ticking inside of her,” says one of her colleagues, former CNN reporter Stefano Kotsonis, and the unsolved mystery of Moth’s personality leaves a hole in the documentary.

Never Look Away

The Bottom Line

Heartfelt but shallow.

Venue: Sundance Film Festival (World Cinema Documentary Competition)

Writers: Matthew Metcalfe, Tom Blackwell, Lucy Lawless, Whetham Allpress

Director: Lucy Lawless

1 hour 25 minutes

Lawless, directing her first film, takes her time and backs into the most revealing and distinct elements of the story. She begins with lovers and colleagues talking about Moth, interspersed with more video of war. We can assume that the footage was shot by Moth, but we’re left to guess whether some of it was not. One of the main talking heads is Jeff Russi, who began his affair with Moth when he was 17 and she was in her 30s, reporting for a local station in Houston after relocating from her native New Zealand. “We’d do acid every weekend,” Russi says. Videos and photos show Moth in her apartment, sitting smoking a pipe or dancing around in a caftan, the picture of someone seeking attention.

Comments from Kotsonis and other colleagues, including Christiane Amanpour, pay tribute to her courage and tenacity in getting the best, close-up images of danger, but their comments might apply to many reporters and photojournalists. “War was the ultimate drug,” Russi says. And as the familiar scenes of war fly by (edited fluidly but without much narrative clarity), the documentary inadvertently reminds us of how inured audiences might have become to such images. Nothing in the first 40 minutes of this under-90-minute film suggests what was so special or different about Moth or her work.

Eventually, the film lands on something: a terrifying sketch Moth drew as a child, black crayoned images of children in closets that evoke Edward Munch at his darkest. Three of Moth’s siblings appear, talking about how their parents beat them, but their brief remarks only raise more questions, leaving us to wonder what they didn’t or perhaps couldn’t bring themselves to say.

At last we hear, from Russi, how Moth invented herself, changing her name from Margaret Wilson to Margaret Gipsy Moth, dying her blonde hair black. All that information would have been useful in the film’s dragging first section. It sheds at least some light on her self-destructive impulses, including her long, obsessive affair with a French heroin addict.

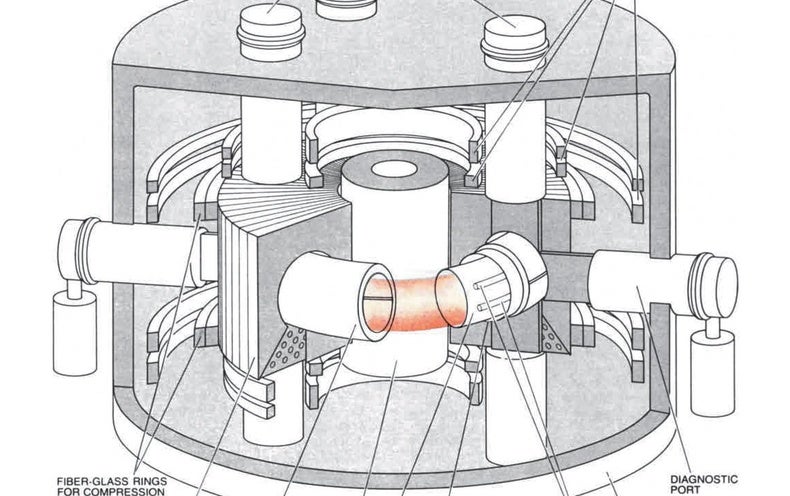

The documentary picks up when it arrives at the most dramatic and tragic moment of Moth’s life. Lawless’ design team created a diorama of “sniper alley,” the street where Moth was shot. It is an effective three-dimensional model because it is eerily empty, focused on the white van Moth was in with three colleagues, including Kotsonis. He recalls hearing her scream when she was shot and seeing her holding her hand to her face. He was not aware that she was actually holding her jaw in place and that she had lost part of her tongue.

The film becomes more dynamic then, but not for ghoulish reasons. Lawless finally shows more of Moth and who she was. There is video of her in the early stages of recovery, some of it hard to watch. Her face is stitched together and she is barely able to talk but is determined to go back to work. Another video shows her years later, after more surgeries improved her face. Her speech is still impaired, yet we understand her when she says, pointedly in the present tense, “I live life to the fullest.”

Other recent, fine films have tackled similar material and never gotten the attention they deserved, including the documentary about women photojournalists (Moth among them), No Ordinary Life and the drama A Private War (2018) with Rosamund Pike as Marie Colvin, killed while reporting in Syria. For all its heartfelt purpose, Never Look Away is a lesser addition to that category.