With 13 features made since 2007, and six in the past four years, French DJ-turned-director Quentin Dupieux is clearly no slacker. Not only has he helmed all these films — he’s also written, shot and edited them, as well as composed many of their scores.

Starting with his surreal deadpan début, Rubber, and up through last year’s Yannick and Daaaaali!, Dupieux has had an impressively prolific run, gradually improving with each new movie while honing a style and tone that are completely his own.

The Second Act

The Bottom Line

It doesn’t get more meta than this.

Venue: Cannes Film Festival (Out of Competition, Opening Night Film)

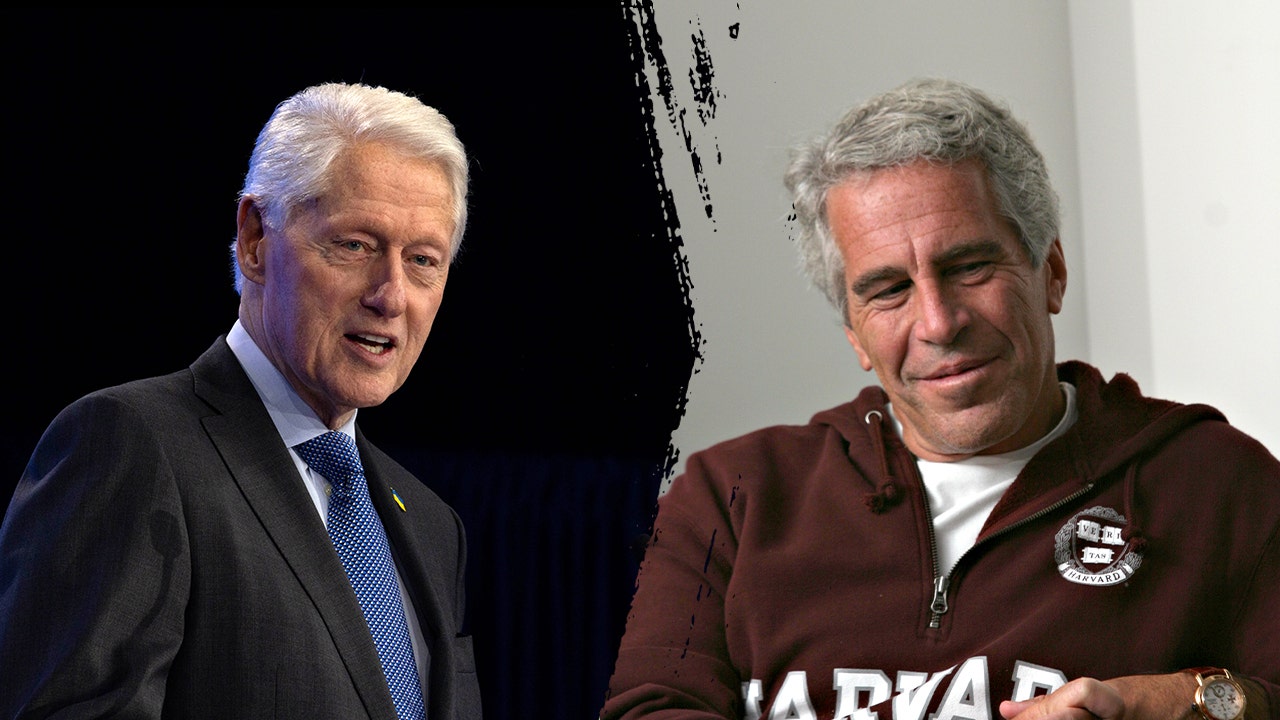

Cast: Léa Seydoux, Vincent Lindon, Louis Garrel, Raphaël Quenard, Manuel Guillot

Director, screenwriter: Quentin Dupieux

1 hour 22 minutes

If, however, there’s one drawback to this incessant activity, it’s that his films all have very short running times because they tend to lack classic denouements. They’re well-executed, high-concept affairs blending comedy, sci-fi, horror and other genres in fun ways, but they often play out like long second acts without real endings.

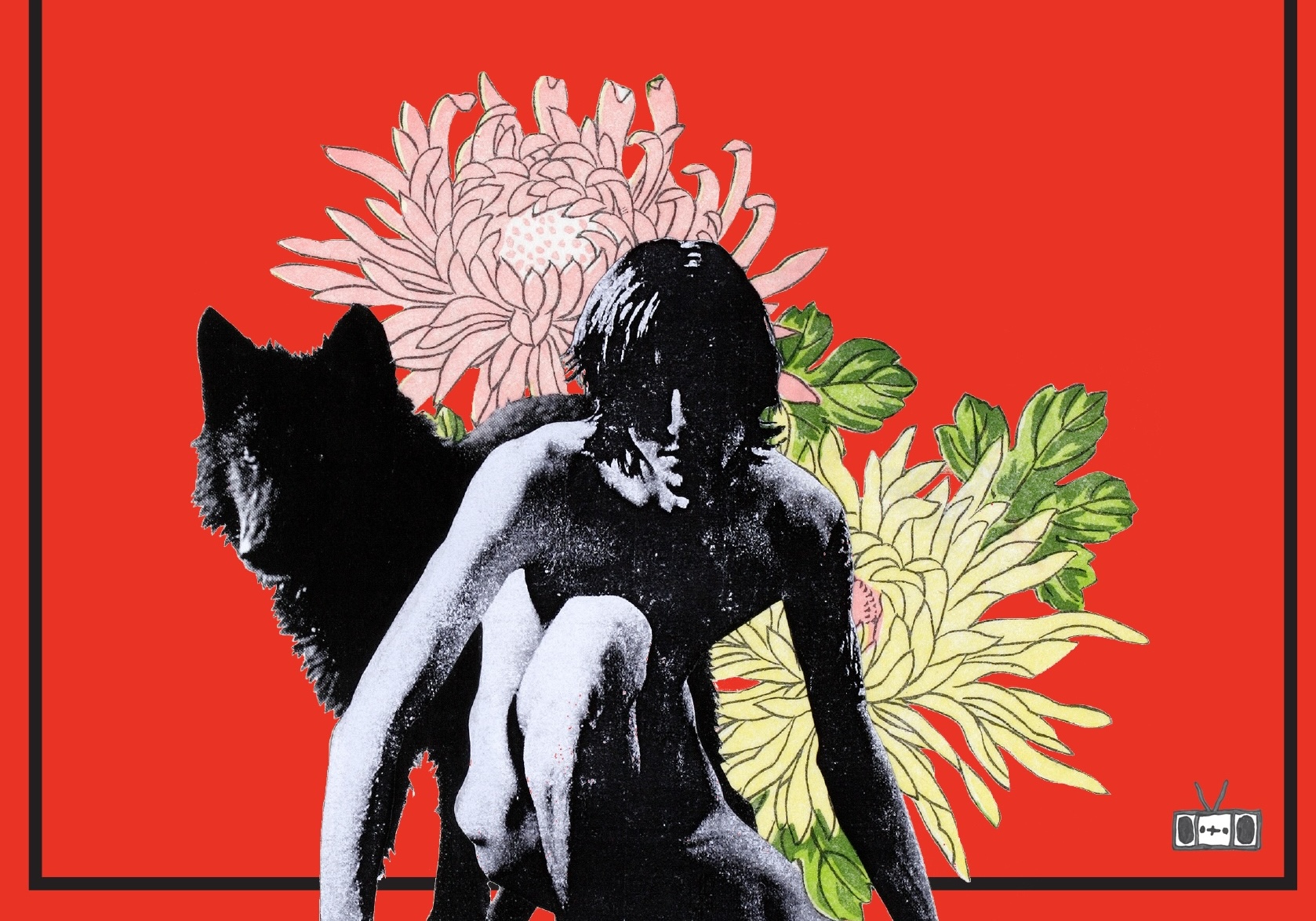

Dupieux was perhaps aware of this flaw when he decided to call his latest feature The Second Act (Le Deuxième acte), although whether he was being ironic or not is unclear. What’s certain is that this is his first work to tackle his own profession head-on, in a Pirandello-esque movie-within-a-movie that plays out like a twisted and uproarious take on François Truffaut’s behind-the-scenes favorite, Day for Night.

Like Truffaut, Dupieux lampoons the infallible egos of some of France’s most famous actors, revealing the sparks that fly when those egos come crashing together on set. But he also addresses more contemporary subjects like the emergence of AI as a tool of cost cutting, and the belated arrival of cancel culture and the #MeToo movement within the French movie industry.

With regards to the latter, rumors that accusations against certain renowned actors, producers and directors could come out in the French press have turned The Second Act into more of a meta affair than Dupieux probably had ever intended — especially since a few of the scenes in his movie address these very issues. This, perhaps ironically as well, may garner the film even more attention when it opens this year’s Cannes Film Festival, along with a near-simultaneous release on French screens.

Dupieux pulls the rug out from under us in the first major scene, which entails an extremely long walk-and-talk between Willy (Raphaël Quenard) and David (Louis Garrel), two friends strolling across the quiet countryside and discussing a girl named Florence (Léa Seydoux) that David wants to set Willy up with. But wait a minute: Willy keeps on looking at the camera, and David keeps telling him to stop saying inappropriate things.

Willy and David are not, in fact, two old friends, but rather actors playing them in a movie. The same goes for Florence and her father, Guillaume (Vincent Lindon), who can barely get through their own scene before losing faith not only in the sappy romance they’re making, but in movies in general. That is, until he gets a call from his agent telling him that Paul Thomas Anderson wants to cast him in his latest feature.

PTA quickly becomes a running gag in The Second Act — a symbol of the sway certain Hollywood directors still hold over French actors, especially those frustrated with their own industry. Other names are dropped as well, including Mel Gibson’s during one hilarious tirade by Willy, while the four French stars seem to be playing only slightly exaggerated versions of themselves: Seydoux is the spoiled starlet unsure of her own talent; Garrel the seductive wiseass who hides his ego behind good manners; Lindon the seasoned veteran with no patience for amateurs; and Quenard the obnoxiously funny newcomer whose working-class origins and diction separate him from the pack.

They all eventually meet up at a roadside restaurant called The Second Act, where they argue some more, oscillating between their characters in the movie being made and the actors they play in the movie about the movie being made. At some point, a nervous waiter (Manuel Guillot) steps in to serve them wine, and his inability to pour out a glass without spilling it all over the place becomes another gag that soon turns horrifically sour.

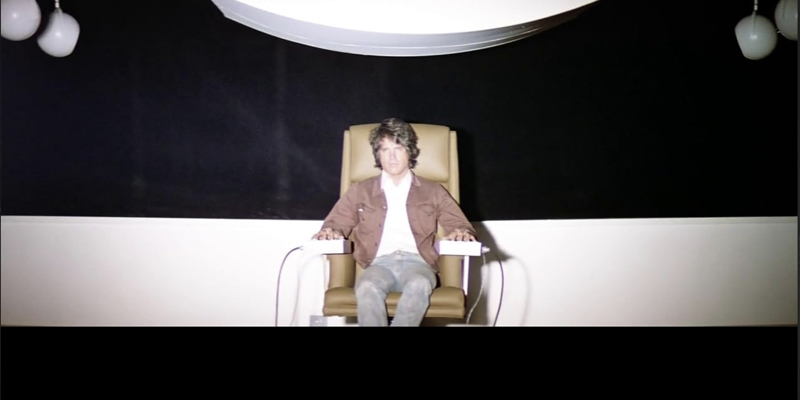

Or has it? Dupieux fools us yet again, with a new twist that has the actors transforming into another set of actors who aren’t playing themselves anymore. There’s also a director, in the form of an AI avatar on a laptop, who shows up to robotically comment on their work, deducting pay from those cast members who didn’t perform adequately enough.

Is this the future of moviemaking? And even more so: Is it necessarily worse than a bunch of narcissistic French stars having panic attacks and ego trips on set? Dupieux doesn’t give us his answer, and like his other films, this one ends without much of a real ending.

What’s different this time around is how his actors — including the charismatic Quenard, who also headlined Yannick — say some very cancel-worthy things that may or may not be the director’s own thoughts, and which in any case are quickly lost in the arthouse metaverse that he’s concocted here. The medium clearly counts more than the message for the former French Touch DJ: It’s cinema as a massive turntable where you can remix, scratch and sample concepts to create your own special sound.

In that sense, The Second Act is probably his strongest film yet, and certainly the first that could stir up any controversy. Not only is the script cleverly written, but the cinematography, including four epically long tracking shots, and the editing, which times all the jokes perfectly, are well-mastered. The fact that Dupieux did all of this by himself definitely merits some kudos.

The director also shows a real knack for making some of France’s biggest current talents funnier than they’ve been before, especially the often dour Seydoux, who delivers one of the film’s most laugh-out-loud moments during a phone call with her mother. There’s perhaps nothing Dupieux can’t do at this point, except, perhaps, try and make a plain old ordinary movie — not that he’d ever want to.