Like most art lovers, the prolific filmmaker Lasse Hallström had never heard of the prolific painter Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) until recently. Af Klint was disregarded, discouraged, sidelined and overlooked during her lifetime, but except for a four-year period, she never stopped creating. She took painting beyond representational still lifes and landscapes and into the uncharted sphere of abstraction, several years before Wassily Kandinsky would claim the mantle of that innovative leap. Her work sat in storage for 20 years after her death, per her instructions, and none of it is for sale.

What a (market-free) discovery of the groundbreaking artist it’s been, beginning with the landmark 2013 exhibit that wowed museumgoers in Stockholm before traveling to seven other European cities and New York. Halina Dyrschka’s 2019 film Beyond the Visible, the first feature-length documentary about af Klint, explores the breadth and depth of her legacy from a revisionist art history perspective that’s nothing short of galvanic. In Hilma, Hallström delves into the fiery and sometimes messy personal story as well as celebrating, in fittingly enthralled, immersive fashion, the singular fusion of nature and spiritual mystery that drove her.

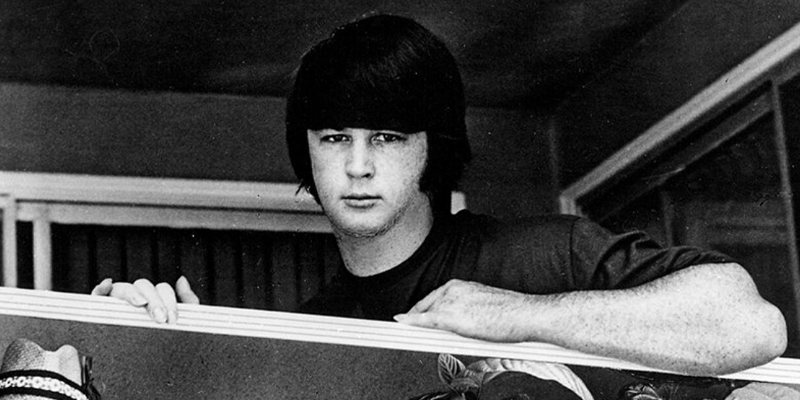

Hilma

The Bottom Line

Spirited and sensuous.

Venue: Palm Springs International Film Festival (Modern Masters)

Cast: Lena Olin, Tora Hallström, Catherine Chalk, Jazzy de Lisser, Lily Cole, Rebecca Calder, Maeve Dermody, Anna Björk, Martin Wallström, Tom Wlaschiha

Director-screenwriter: Lasse Hallström

1 hour 54 minutes

The English-language drama (Hallström couldn’t find the funding for a movie about his fellow Swede in their native language), which had its North American premiere at the Palm Springs festival, is set for an April stateside release by Juno Films, and looks destined for a warm art house welcome.

I can’t pinpoint when I first became aware of af Klint’s work — maybe it was the mood-setting shoutout in Olivier Assayas’ Personal Shopper — but I do recall the feeling of recognition sparked by her vibrant abstract images, a reconnection, over the click-click-click of deadlines, with a language of transcendent timelessness. Writer-director Hallström was pointed af Klint’s way by his wife, the actor Lena Olin, and the film they’ve made together is a family enterprise, at its center an impressive debut lead performance by the couple’s daughter, Tora Hallström. (It’s a promising reinvention, too; as a teenager, she made two brief appearances in her father’s features, but until Hilma, she’d been working in the world of finance.)

Playing the title character over a period of decades, Tora Hallström embodies the perennial outsider looking in, whether in her family, at school, in society or, crucially, in the realm — and big business — of fine art. (Refreshingly, her aging is subtly signaled, rather than emphasized in the hyper-visual manner of many films, but at key narrative junctures the passage of years could be clearer.) Tora brings an earthy physicality to the role, along with an apt headstrong energy. The movie is bookended by potent scenes of Olin as the elder Hilma, being turned away, as she has been throughout her life, by men of status and money. She’s a “witch” to them, beyond comprehension, and though there’s profound fatigue in her eyes, there’s also an undimmed hunger as she takes in the simple beauty of trees lining a city street.

Hallström traces Hilma’s birth as a convention-defying artist to the childhood death of her beloved younger sister (Emmi Tjernström). Together they explored the island Adelsö, where their naval family possessed ancestral land, if not a great deal of money, and an aristocratic name. For Hilma, their investigations of the natural world and her paintings of flowers and seashells are a matter of science, not ornamentation. “Art is a tool in my research,” she tells the skeptical committee of men who interview her for admission to the art academy, where female students must use a separate entrance in the back of the building.

She’s determined to create a map of the world that encompasses the physical and the unseen. Her alertness to both realities has vivid, kinetic life in the movie, thanks to Ragna Jorming’s expressive camerawork, Jon Ekstrand’s stirring score, the sensitive pulse of Dino Jonsäter’s editing and the rich, heightened palette of Catharina Nyqvist Ehrnrooth’s production design and Flore Vauvillé’s costumes. All of this is orchestrated with heart and soul by Hallström, and, notably, without a hint of sentimentality. The accent is on firsthand experience, revelation and invention, and the inner strength of a woman who stays true to herself.

The director’s screenplay devotes a substantial amount of time to De Fem (The Five), the group that Hilma forms with four other women she meets in art school: the medium Sigrid Hedman (Maeve Dermody), Cornelia Cederberg (Rebecca Calder), Mathilda Nilsson (Lily Cole) and Anna Cassel (Catherine Chalk). Together they study Theosophy and spiritualism, fashionable at the time rather than outré, as they are today. Hallström treats these fields of inquiry with respect and a sense of wonder. The women experiment with automatic writing via a planchette, and they make art collectively, with Hilma at the helm, guided by spirits. Anna, who has ample family money, bankrolls Hilma’s projects — matters of great urgency for her and, she’s certain, for the world. In what might be a matter of conjecture, Anna is not just Hilma’s benefactor but also her lover, their sensual connection subtly conveyed in one of their first scenes together, a visit to the dressmakers where the interiors’ mix of opulence and utility seems to glow from within.

When Hilma’s mother (Anna Björk), as tentative as her daughter is rebellious, needs a nurse, Anna pays for that too, only to find that the woman hired, Thomasine (Jazzy de Lisser), is replacing her in Hilma’s affections. To the credit of Hallström and the two lead performances, Hilma embraces complexity and has no use for pedestals or hero worship. Still, though, the ups and downs of Anna and Hilma’s relationship, the jealousies and stops and starts, grow repetitive and tiresome midway through the film. That these sequences are meant to convey not just Hilma’s demanding willfulness but also her artistic stasis is clear, but the story’s true engine, Hilma’s creativity, feels lost in the melodrama.

For all her self-confidence, Hilma succumbs with painful extravagance to the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner. A brilliant historical figure, played by a perfectly supercilious Tom Wlaschiha, he’s the occultist she holds above all others, even after she entreats him to support her art and he responds with prescriptive notions about what art is and why her work doesn’t qualify.

But it’s not all mansplaining for Hilma; in a wonderfully awkward encounter with Edvard Munch (Paulius Markevicius) at an exhibit of his paintings, he offers encouragement, however general, and however much it’s inspired by her reaction to one of his canvases. Relying on others’ generosity, Hilma creates a kind of utopia, an island atelier where she can make large-scale paintings for the temple she envisions. Guided by spirits, hindered by the art-world establishment, she finds a way to triumph, albeit at great cost, and Hilma embraces the nitty-gritty along with the rapture.

![[Oops! Corrected Link] Read Harder 2025 Halfway Check-In Survey [Oops! Corrected Link] Read Harder 2025 Halfway Check-In Survey](https://s2982.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/read-harder-2025-check-in-survey.jpg.optimal.jpg)