[This story contains major spoilers from The Brutalist.]

Joe Alwyn first read the script for Brady Corbet‘s 3.5-hour epic The Brutalist five years ago.

The pair met for coffee in New York. “I was such a such a fan of Brady and such a fan of the script,” the British actor tells The Hollywood Reporter. “It was this big, rigorous, detailed, old-fashioned epic.”

He was immediately game, though it would take another few years before the post-war piece landed on our screens. “Good for [Brady] for fighting tooth and nail to get it made,” Alwyn says.

The Brutalist has set the pace this award season, earning seven Golden Globe nominations and plenty of Oscar buzz. Corbet and his cast have built a masterpiece of cinema; with a built-in intermission and a sub-$10 million budget, critics have lauded Corbet for his achievement, and Alwyn is among one of his biggest fans.

The architecture-themed immigrant drama, penned by Corbet and his partner Mona Fastvold, stars Adrien Brody as fictional Hungarian Jewish architect László Tóth, who flees Europe after World War II to build a new life in America. He falls into the circle of a wealthy businessman, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) and his children, Harry Lee (Alwyn) and Maggie (Stacy Martin). The elder Van Buren commissions an enormous community center from László, whose wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) is finally able to join him in the States thanks to help from Pearce’s lawyer friends.

Pearce and Alwyn’s dynamic is fraught with tension: a son desperate to find a place in his family and earn love from his father, who brazenly overlooks him. They live in a vast home and look down upon the immigrants now in their lives, despite the welcoming facade. “He has enough power and the money around him, but probably not enough love,” Alwyn says to THR about his character. “I was interested in what that does to you, and how that can stunt you.”

At one point, it is implied Harry has his way with László’s young niece (Raffey Cassidy), though this escapes retribution. The family’s unraveling comes when Jones’ character confronts Van Buren about raping her husband. Harry’s denial is furious and while a struggle to remove Erzsébet from their home ensues, his father disappears.

Below, Alwyn unpacks the opaque ending to The Brutalist and dives into Corbet’s “economical” filmmaking. He discusses how his director managed to make this movie on an $8 million budget (“It’s like the price of some episodes of TV these days!), the unanswerable quality of capitalist American families like the Trumps and why this film should set an example for the industry: “It doesn’t have to fit a cookie cutter shape and it doesn’t have to be a $100 million, $50 million, $20 million production. If you tell a story with intent and imagination and you assemble a good group of people, then those things can really work.”

***

Congratulations on a fantastic performance, Joe. I’m really intrigued as to how you got on board The Brutalist.

I read it in 2019 I think, and I asked if I could meet Brady, and I saw that the part [of Harry] wasn’t cast, and I had a coffee with him in New York. Firstly, this is pre-COVID, which is another world away. And we chatted for ages and got on. But it wasn’t all set up at that point. So it was this moving thing. And then I think it came together and fell apart in various shapes over the next few years. I think all of us at some point weren’t in it. My part was going to be a little older, and then eventually, by the time it changed shape again post-COVID, I was very happy to get the call up.

I was such a fan of Brady and such a fan of the script. It was this big, rigorous, detailed, old-fashioned epic. I just hadn’t read anything like it before and it felt very complete, even on the page, and very special on the page. You never know how anything’s gonna turn out, but I think he did such a fantastic job. I’m so happy to be a part of it.

It’s such a unique film. The script, the built-in intermission. It feels like something cinema hasn’t really seen before.

Or hasn’t seen for a while. It does feel like a big, old-fashioned film, and there was some more modern references I felt when reading it, like There Will Be Blood, obviously. Even Foxcatcher I was reminded of a little bit. The fact it’s shot in VistaVision and 70mm and as you say, an intermission, it feels very refreshing. And good for [Brady] for fighting tooth and nail to get it made. I think he was trying to do it for so many years. And then the shoot itself was in 33 days and the budget was, I don’t know, $7-8 million? Not a lot for what it is when you see the scope of it.

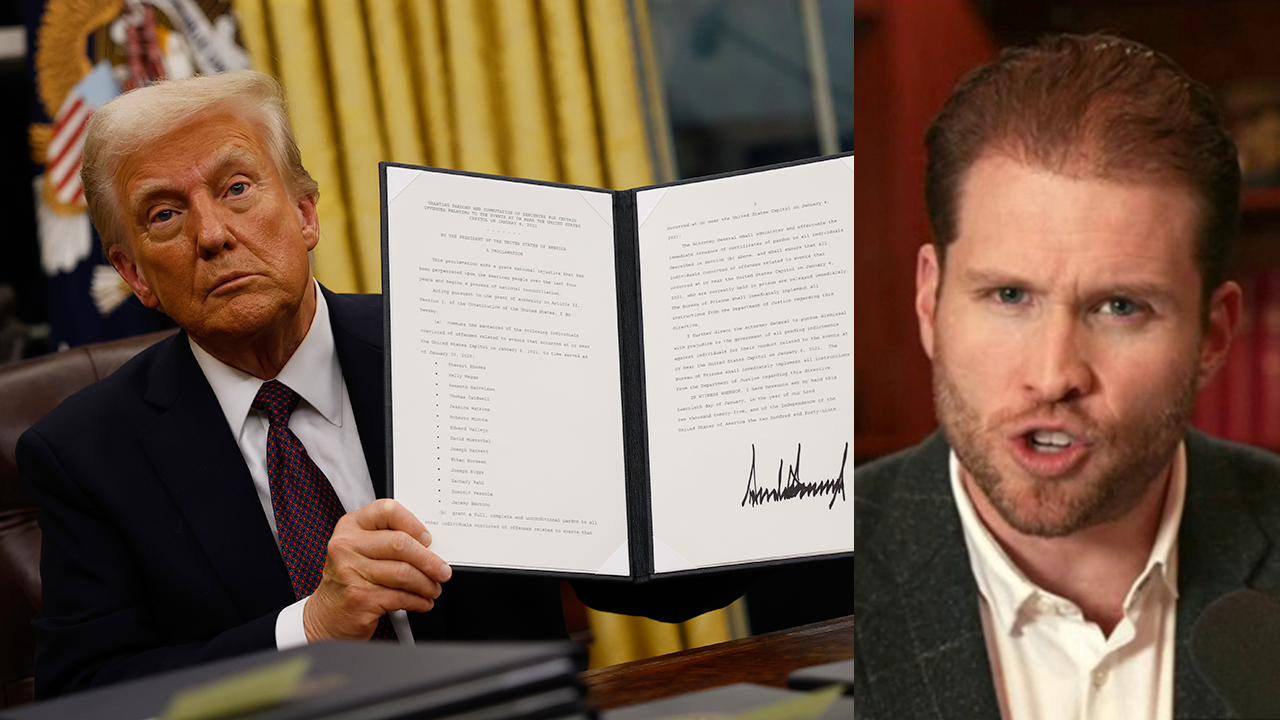

Adrien Brody and Joe Alwyn as László Tóth and Harry Lee Van Buren in The Brutalist.

a24

I was so shocked when I found out about the budget. In hindsight, there were small moves Brady made that showed how he really worked around that budget and got creative.

It’s like the price of some episodes of TV these days! I think he’d obviously had it in his mind for so long that he knew exactly what he wanted to do and how he needed to shoot it, just in terms of the time constraints. And so when we got on set, he shot it almost as he edited it. I don’t mean he was editing it at night, but what you see is what was pieced together on the day. He was very economical. Everything’s in one take, which looks great, but it also saves time — you don’t have to do lots of coverage and turnarounds. So he knew he was up against the clock, but also perhaps that some of those restrictions favored his creative sensibility for the film. It never felt madly rushed on set.

How difficult is that for you as an actor, those one takes? Juicy or daunting?

It’s a bit of both. I really liked it. I’ve done some of them before but a few times, at least in my scenes, Brady had them in this film. There’s a pressure because you know that if something is off in the tape, then it’s going to be there. But at the same time, because they’re quite long, they feel like little pieces of theater and that’s quite nice to do. You’re not fragmenting things, you’re not chopping and changing. You’re not going over each other’s shoulder, and it’s not taking all day to shoot a two-minute scene. Once you get into the rhythm of the shape of the scene, you can just go again and again and again. So you do — if there’s the time you get to do it — four or five takes.

I think the most challenging one, just geographically and practically, was at the end when Felicity’s character comes to accuse Guy of what he’s done because that moves all throughout the house. But it’s fun doing a six, seven-minute take like that, and it takes you around different spaces and through different intensities of performance. I really loved [Corbet’s] way of working.

It’s so good. It’s a portrait of a marriage in lots of ways, this film, and this inherent otherness of immigrants. There’s an insurmountable hurdle for them. But of course, it’s also about architecture, the force of capitalism. What resonates with you?

It at least opens up the door of conversation about so many things. It’s so huge in its scope and also so personal and intimate in its storytelling. But as you say, the ideas of being an immigrant coming to America, the American dream, art versus commerce. Those are the big ones that jump out.

I was really interested in those big, American, capitalist families and thinking about Harry — where he fits into that, where he’s grown up with too much of one thing and not of enough of the other. He has enough power and the money around him with his father, but probably not enough love and not the right kind of love. I was interested in what that does to you, and how that can stunt you, and how he’s searching for his identity in his family, in this big organization and structure. And he’s constantly searching for his dad’s approval. It makes me angry, the invincibility of families like that. Obviously, there is a degree of comeuppance at the end. But you see it often. You see it with the Trumps. You see it in Succession. You see it all over the place. The unanswerable quality to people and the [fact] that with enough money and legal teams at your disposal, you can dispose of who you want.

Had you worked with Guy or Adrien before The Brutalist?

I worked with Guy twice before on a couple of things. It was really nice seeing him and having him be my dad. That was lovely. With Adrien, I hadn’t [worked with him] but was obviously very aware of his work. Having that familiarity with another actor or director or someone in the crew always helps. I think it’s a really interesting relationship between Harry and Harrison.

We get these little glimpses of it that tell us so much about the dynamic there, but we don’t see it in full. Brady and Mona let us fill in the gaps.

Yeah, [Harry’s] constantly put down, if you think about it, here and there, with snide little comments by his dad. And obviously Harrison’s relationship with László comes about because Harry is trying to surprise his dad and do something nice for him by building this library, which then goes wrong at the beginning and Harry gets the blame for that. So I think he’s initially got a chip on his shoulder about this architect who’s suddenly come into his life and been taking under his dad’s wing in a way that Harry never has. But it was amazing working with Guy again, and I’ve always noticed, the last two times as well, his level of focus and the way he interrogates the scene. It’s so impressive to watch. He picks everything apart in such a smart way, but then just throws it away in the doing of it.

Alwyn and Guy Pearce play father and son in The Brutalist.

a24

I have to ask: that ending is a little murky, isn’t it, where we witness this entire unraveling of the whole family when Erzsébet comes to confront Harrison, who then goes missing. Is there something more concrete there that audiences have so far missed?

I had a text from a friend asking me the same thing yesterday. I think in the script it’s probably clearer than is shown on screen. There is a line, maybe it’s even buried somewhere in the film, when they’re searching for him and someone says, ‘We found something.’ I don’t remember if it was explicit as, ‘We found a body,’ but I think the implication is that he’s killed himself. But I quite like that it’s opaque, and you don’t end on a shot of him in this monument, dead. But yeah, I’m pretty sure that’s what [the ending is].

That is extremely helpful. I was worried I hadn’t picked up on something.

A couple of people have actually asked me about the moment between Harry and Erzsébet at the end, when he takes her out of the house. His reaction is so big to the accusations against his dad and a few people have said, is that because he has experienced something similar in the past? And it’s not something that I gave a huge amount of thought to while shooting it, but I found that an interesting commentary. It does make sense, I think, and it’s kind of threaded throughout, but it was never there in the script. Brady never said anything about it. There’s a mixture of anger and shock and shame, but perhaps there’s some kind of buried trauma there as well.

Have you been surprised by the reaction to the film? Critics have loved it. And now The Brutalist is the recipient of so much awards buzz.

Yeah. I think you just never know how anything’s gonna do. And I think Brady has said this, it’s a film that ticks so many boxes of what isn’t made these days, given what it’s about, given the length, given the subject matter. It’s not an easy sell in some ways. And so whilst it felt like a really lovely thing to be involved in and a great script and a great experience shooting it, you just don’t know how that’s going to land. And so to see it be met so warmly is, yeah, it’s always such a bonus. But going to Venice [Film Festival], it didn’t have a distributor, so I think everyone just didn’t know what was going to happen to it.

What kind of roles are you going for at the moment? Is there anything you really want to do that you haven’t done?

I don’t think about it in a bullet point list or too forensically, but I suppose I want to try and not repeat myself too much. I’d love to play against type more and more, whatever that means from the outside in. The Brutalist was a good example of that, a big, old-fashioned American character where you’re learning a Hitchcock, transatlantic accent and everything’s slightly larger than life. But no, I think I’m just trying to find interesting, exciting people to work with and see what parts come with them. And challenge myself and be a part of things that speak to me and punch me in the gut — in the right way.

Is there anyone you haven’t worked with that you’d love to?

So many people. I assume you’d like answers? [Laughs.]

Yes please!

Director-wise I’m thinking, even from the crop of films this year, I’d love to work with Rob Eggers. I’m a big fan of his. I haven’t seen Nosferatu yet but I can’t wait. I’ve met him a few times in the past, and yeah, I really like him as a person. I think he’s such a talented filmmaker. I’d love to work with him. But there’s so many people.

There has been such a wealth of great films this year. What have you enjoyed, and what kind of place do you think the industry is in more generally?

There’s still so much I need to see. I liked Anora, I thought Mikey Madison was amazing. And Sean Baker, I’ve always liked his films.

I’m never very good at answering that [second] question, because I never really know, to be honest. Not to turn everything back to The Brutalist, but if you make a film with such ambition like that, like Brady has done for the budget that he did, and if people do like it — fingers crossed they do — then I do think it’s good. It’s a good sign for cinema that people want stories like that. It doesn’t have to fit a cookie cutter shape and it doesn’t have to be a $100 million, $50 million, $20 million production. If you tell a story with intent and imagination and you assemble a good group of people, then those things can really work.

The Brutalist is now playing in U.S. theaters.