It’s been over seven-and-a-half years since acclaimed filmmaker Jeff Nichols last had a film in movie theaters, and with tonight’s release of The Bikeriders, the interminable wait for his sixth feature is now over. In the aftermath of his two 2016 releases, Midnight Special and Loving, Nichols knew he needed to take a step back and rejuvenate himself, creatively. However, through no fault of his own, his breather became far more prolonged than intended due to a variety of unforeseen circumstances including 2019’s Disney-Fox merger, 2020’s pandemic and 2023’s double strike.

In the case of the Disney-Fox merger that was completed in 2019, it effectively ended Nichols’ four years’ worth of development on his Alien Nation film. The Arkansas native had already been working on an original sci-fi film, but at the urging of 20th Century Fox, he agreed to retrofit his script for the sake of using a recognizable IP as a springboard. Ultimately, the project, at least in that form, wasn’t meant to be despite completing prep and casting.

In 2022, the Take Shelter and Mud filmmaker then pivoted to his long-gestating idea to adapt Danny Lyon’s 1967 photojournalistic book, The Bikeriders, which chronicles a Chicago-area motorcycle club in the mid-1960s. Nichols was initially turned onto the book by his older brother, Ben Nichols, at least two decades ago. Ben is the frontman for the Memphisian rock band Lucero, and in 2005, he channeled his own love for Lyon’s book into a song called “Bikeriders.” In turn, the song would serve as a frequent reminder for Jeff to do his own fictionalized take, one that would also include the love story of Kathy (Jodie Comer) and Benny (Austin Butler).

“We were both inspired by [Danny Lyon’s The Bikeriders] in our own respective mediums, but I’ve been listening to that song since it came out in 2005. I just had it in a playlist, and every once in a while, it would come up on shuffle. And I’d be like, ‘Man, I’ve got to write that biker movie,”” Nichols tells The Hollywood Reporter.

By late 2022, Nichols had assembled a tremendous ensemble that boasted the likes of Comer, Butler, Tom Hardy, Michael Shannon, Mike Faist, Norman Reedus, Boyd Holbrook and Damon Herriman. However, another potential snag emerged when Butler’s preceding film, Dune: Part Two, expected him to shave his head to play the hairless baddie, Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. So Nichols respectfully issued a plea to Butler, and while Butler credits Denis Villeneuve and his team of producers for accommodating the request with a bald cap, Nichols praises Butler for ultimately protecting his film.

“We had a conversation, and I was like, ‘Look, man, you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do. It’s Dune: Part Two. Dune was one of my favorite movies of 2021. But our character really doesn’t work with a shaved head,’” Nichols recalls. “And, fortunately, he fought for that for us. It’s not like I got on the phone with Denis Villeneuve and was like, ‘Hey, please don’t shave his head.’ Austin worked it out for us, and I love him for that.”

Nichols then shot the film in late 2022, targeting a fall 2023 festival run that eventually turned into an Aug. 31 premiere at the 50th Telluride Film Festival. From there, 20th Century positioned the crime drama for a December release in the midst of awards season. However, the industry’s double strike then upended that release plan due to not having the star-studded cast available for advanced promotion. In November, Focus Features, who put out Nichols’ 2016 drama Loving, then came in and acquired the film’s distribution rights from New Regency, opting instead for a summer 2024 release and a robust promotional campaign.

Despite these never-ending obstacles en route to his sixth feature, Nichols remains rather zen about the dynamic turn of events, namely due to his wife’s assessment of the situation.

“I live in Texas. I don’t live in L.A., and when I talked to my wife about it, she was like, ‘Nobody gives a shit about this,’” Nichols says. “Everybody in the industry is all concerned about dating and everything else, but she was like, ‘The rest of the country doesn’t care about that. They’ll go see it when they go see it.’ So I had to adopt that philosophy.”

As for the future of his Alien Nation project, the original, non-IP version of his script is currently at Paramount where he hopes to finally make the $100 million project.

“I’m trying to [get it made] right now. It’s a big movie, though. It’s an expensive movie, and the truth is, when you want to work at those budget levels, you just have to turn over control to that system,” Nichols says. “And that system is strange. That system is complicated, and sadly, it operates a lot of times out of fear. Nobody wants to get fired, nobody wants to mess up. It’s a tremendous amount of money that they could spend on something like that, and I don’t have control over it.”

Nichols adds that he’s more than willing to compromise if it means working at a bigger scale for the first time, something he’s always envisioned doing someday. It’s not his ideal scenario, but his strong belief in his story means he’s open and ready.

“I can maybe make it for under $100 million; we can pull levers like that, but it’s going to have to be made in that system. And I don’t want to work in that system. That’s not my desire,” Nichols admits. “I don’t want to have to jump through these hoops, but I want to work in scope. I want to work in scale. I always have. So I want to try my hand at it, and I think I have a story that warrants it. We’ll see if the universe aligns in order for me to make it. I don’t know. But I’m not scared of it because I know what the story is. If they’ll just let me make the story, then things will be alright.”

Below, during a recent conversation with THR, Nichols also discusses how valuable Ben Nichols was as a sounding board for The Bikeriders, before addressing the potential connectivity of his Arkansas-based stories.

Well, I hate to make you account for the gap again, but for the uninitiated, the eight years that passed between films were a byproduct of four years developing Alien Nation, the Disney-Fox merger, the pandemic and the double strike?

Yeah, you got it. That was it. I’m not really a filmmaker who strategically thinks about their career. I put all my eggs in one basket, and when one doesn’t work out, it takes me a little while to get started on the next one. I don’t write multiple things at once. But I was pretty clear when I finished Loving. I was on that tour and people asked me what was next, and there’s this quote from Mark Twain that said, “Creatively, you have to fill up the well.” It actually gets empty. You can drain it, creatively. And, in 2016, I felt like the well was empty. I had to go do some work to fill it up. So I’m slowly starting to collect a group of scripts now, and hopefully, if the world stays stitched together, I’ll get to keep making movies over the next five, ten years.

Actor Mike Faist as Danny Lyon and director Jeff Nichols on the set of The Bikeriders

Kyle Kaplan/Focus Features

Whenever I interview your friend David Gordon Green, we talk about how many movies he’s made since your last movie in 2016, and last October, we both anticipated the end of the streak at five. Well, six weeks later, The Bikeriders was delayed again. After yet another obstacle, did you start to think the universe was working against you?

I don’t really know what good that would do. You just keep thinking about how to get the thing out into the world. I remember when I made Shotgun Stories, I had it on my laptop, which was just this MacBook Pro, and there was a moment where I thought, “This movie may never exist anywhere outside of this computer. It could literally die on the vine.” So you can get really lost in that kind of fear because, as we well know, making a movie is a fricking miracle. Getting a movie released is impossible, and so you just have to keep your eye on the end goal, which is getting this thing out to the public. None of us want to work in obscurity. We want these films to be seen.

So you’re staring down the barrel of, “Okay, well, do we go to Telluride? Do we accept that? If we don’t accept that, then we’re already conceding defeat in terms of this film’s release in the year of 2023. And who knows, maybe the strike could end in two weeks.” There was that real moment at the end of August, beginning of September, where people were saying, “Nope, they’re about to solve this thing.” So that’s the atmosphere in which we made the decision to go to Telluride, and fortunately enough, we got invited to Telluride in the first place.

But then we had this drop-dead date on the calendar, and it was like, “If this thing’s not resolved by now, then there’s just no way we can responsibly release this film. It’s too great of an investment. It’s too much of a risk. You have a cast like this, and you’re not going to let them go out and promote it? That’s like walking into a firing squad. That’s a bad idea.” So, ultimately, we came up with this solution, and now I’m really excited about it. I love the fact that it’s coming out in the summer. We can have people ride up on bikes and do all this other stuff. I live in Texas. I don’t live in L.A., and when I talked to my wife about it, she was like, “Nobody gives a shit about this.” Everybody in the industry is all concerned about dating and everything else, but she was like, “The rest of the country doesn’t care about that. They’ll go see it when they go see it.” So I had to adopt that philosophy.

Assuming that you and your brother (Ben Nichols) discovered Danny Lyon’s book, The Bikeriders, at the same time, did he go off and write the Lucero song while you let a movie idea percolate?

Yeah, that’s it exactly. He found the book at Barnes & Noble and I found it in his apartment. We were both captivated with it, so I would eventually write the movie, but he wrote the song first. So we were both inspired by it in our own respective mediums, but I’ve been listening to that song since it came out in 2005. I just had it in a playlist, and every once in a while, it would come up on shuffle. And I’d be like, “Man, I’ve got to write that biker movie.” So I love his song, and we have it over the end credits. There’s something about it. It has a feeling that I love dipping myself into, and so he was a great person to talk to about it, because he was obviously inspired by these stories in his own right.

So I would call him late at night as I was working on the script and say, “I’m thinking about this, and I’m thinking about maybe fictionalizing this. What do you think about the name of the Vandals? Is that a good fictional motorcycle club name?” And he’d say, “Well, there’s a punk rock band called The Vandals.” And I was like, “Yeah, I know, but I think we can get away with it. I don’t think there are any motorcycle gangs [with that name]. And Kathy is definitely going to be the narrator. What if I broke her narration into three separate timelines? That way, we get three separate Kathys, and I change her personality subtly between these three timelines.” And he was like, “That all sounds like a good idea.” So Ben is the one I would always check things against in terms of cheesiness. (Laughs.) He’d tell me if I was going too far.

Austin Butler as Benny in Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders

Kyle Kaplan/Focus Features

You recreated several photos from the book, such as that iconic bridge shot of Benny (Austin Butler). Did you scout a comparable bridge that was convenient to your primary shooting location?

Yeah, it was comparable. We shot in Cincinnati, which is right on the Ohio River, and that original photograph was taken in Louisville. It’s the same river, but a different bridge built in the same era. And as we were driving around scouting all these other locations, we were just like, “Man, that is the bridge. That looks just like the bridge. We’ve got to get that in the movie.” And it wasn’t actually scripted that way. I knew I wanted Benny leaning over the pool table; that was baked into the script, but I didn’t know we would be able to find a bridge like that. So I had this epiphany as we were starting to storyboard and break down that chase sequence. We had to be very specific about it because it’s a period piece, and you can’t just go shoot a motorcycle chase scene. You’ve got to really be specific about your wedges, and the chase sequence was scripted to begin in town and end in this rural area. So it was like, “What if the bridge that he goes over connects the town part from the rural part? Ah, that makes total sense.” So that bridge was just sitting there, and that was just fortune smiling down on me.

Director Jeff Nichols and actor Austin Butler on the set of The Bikeriders

Kyle Kaplan/Focus Features

I brought up some misfortune moments ago, but you did have some more good luck as Austin Butler agreed to not go bald for Dune: Part Two, which filmed right before The Bikeriders. Did your head start to spin when the idea of Austin in a wig was floated?

It wasn’t in the ether very long. It was like, “Oh, they want him to shave his head.” So we had a conversation, and I was like, “Look, man, you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do. It’s Dune: Part Two. Dune was one of my favorite movies of 2021. But our character really doesn’t work with a shaved head.” (Laughs.) And, fortunately, he fought for that for us. It’s not like I got on the phone with Denis Villeneuve and was like, “Hey, please don’t shave his head.” Austin worked it out for us, and I love him for that.

Your films all take place in the South or the Midwest, and they all follow blue-collar people, as well. This question is likely a byproduct of this current shared cinematic universe era, but have you ever imagined any connections between your films? Could the Hayes brothers from Shotgun Stories ever cross paths with Ellis from Mud?

They could, yeah. But it’s such a strange question because all these characters are such specific products of the place that they come from. So the only two you could overlap, really, would be the Hayes Brothers with Ellis, because they’re both from Southeast Arkansas. There’s similarities to the Lovings, but they’re in Virginia. Take Shelter, by benefit of a bad producer that I didn’t like, had to be shot outside of Cleveland, so [Arkansas] became Ohio, and those worlds don’t overlap. If you’re going to really commit to regional specificity, then you’ve got to really commit to it, and that means they don’t get to cross paths. They don’t get to cross oceans of time. They are where they are because that’s who they are.

You always want an ensemble that’s filled with great actors, but are Mike Shannon and Paul Sparks also a matter of superstition at this point?

Shannon, maybe, but not Sparks. I think Paul Sparks is one of the greatest actors going, and we need more Paul Sparks movies. I would love to see him in the lead role of a bigger film. I don’t know if it’ll happen or when it’ll happen, but I sure hope it does happen. But Mike is different. He is not just a collaborator; he has become family to me. I owe my career to Michael Shannon. I learned how to direct from directing Michael Shannon. So, from the outside, it can feel kind of cute, but it’s not. I love that guy, and I want him in movies because he’s the greatest actor in the world. And if you’re a director and you have access to the greatest actor in the world, it makes sense that you would call him all the time.

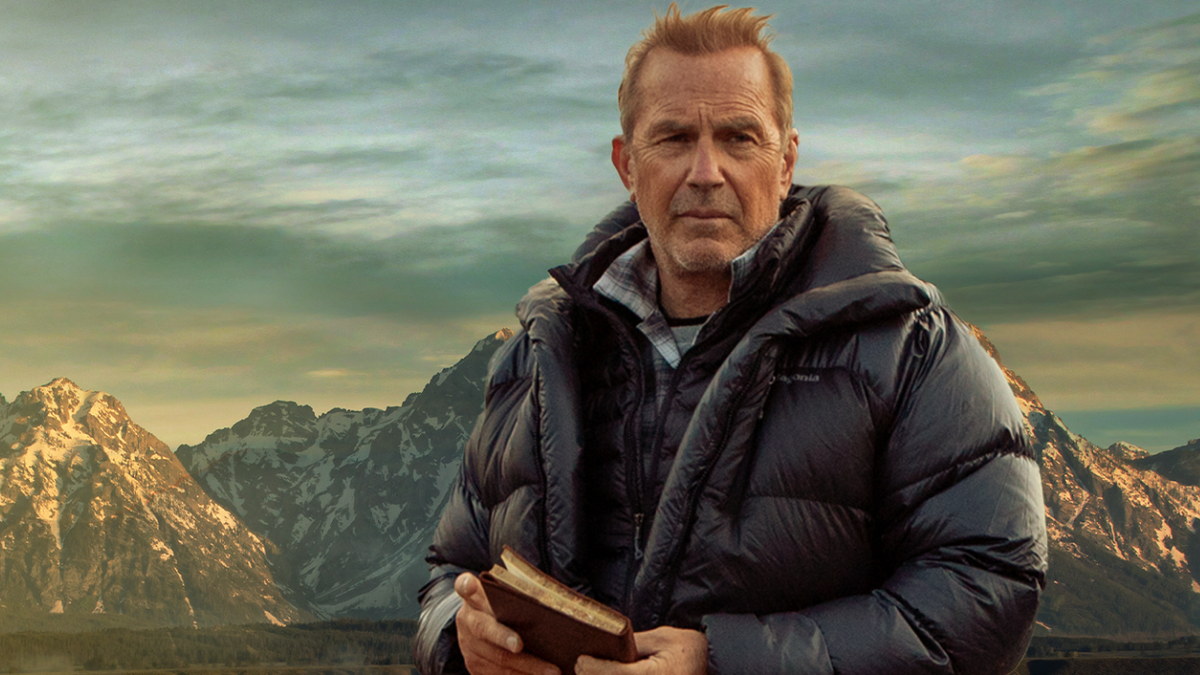

Austin Butler stars as Benny in Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders

Courtesy of Focus Features

To me, The Bikeriders ultimately says that a man expressing his emotions is not emasculating. It’s the culture that has conditioned men to think that it’s emasculating. So I appreciate that point at a time when arguments are being made to restore the outdated dynamics of years past.

There’s a tension in masculinity. It’s complex. There’s a duality to it. We should recognize that there are parts of masculinity that are undeniable and attractive, but there are also parts of it that are aggressive and violent. Everybody uses that word toxic. But that tension is really what The Bikeriders is talking about. You can actually hold these two things at once in the same space, and boy, isn’t that frustrating? Isn’t that challenging?

Take a motorcycle, just as an example. A motorcycle is beautiful. You want to get on it, you want to ride it, but it can kill you. There’s a tension there. It holds both things at once, but we’re drawn to it. And so The Bikeriders very clearly became about this piece of human behavior where we’re drawn to things that are dangerous for us and that we know are dangerous for us. Why? Why do we do that? Because we do, and I think it has something to do with trying to find an identity for ourselves.

In this day and age, more than ever, people want to be unique. They want to have their own identity, whether that’s defined through sex or race or sexual orientation or anything else. “This is me. This is who I am. I’m not a monolith. I’m not part of anything. I’m unique.” And maybe, just maybe, by being associated with things that are dangerous and things that could hurt you, that gives you a leg up in the identity battle and in defining yourself to the world. Maybe that’s what’s going on. To be honest, the movie really doesn’t set out to answer that question; it just sets out to pose it.

Between Alien Nation and A Quiet Place: Day One not working out, do you think that closes the book on you and franchise storytelling? Can you make a Jeff Nichols movie in that environment?

I hope so, because I’m trying to right now. The script that came out of the Alien Nation processes is at Paramount right now. It’s under a different title, an original title, because it was an original script that I wrote [before retrofitting it as Alien Nation]. So I would love to make it, but it’s a big movie, though. It’s an expensive movie, and the truth is, when you want to work at those budget levels, you just have to turn over control to that system. And that system is strange. That system is complicated, and sadly, it operates a lot of times out of fear. Nobody wants to get fired, nobody wants to mess up. It’s a tremendous amount of money that they could spend on something like that, and I don’t have control over it.

On Take Shelter, for instance, we wanted $2 million to make that film, but nobody wanted to give it to us, so we made it for $650K. You just pull these levers to make the thing happen, but I can’t do that with this sci-fi film. I can maybe make it for under $100 million; we can pull levers like that, but it’s going to have to be made in that system. And I don’t want to work in that system. That’s not my desire. I don’t want to have to jump through these hoops, but I want to work in scope. I want to work in scale. I always have. Even if you look at Shotgun Stories, that’s an independent film that cost my family $50K to make, but the emotional scale of that film felt big to me. Even the look, shooting in 35 millimeter and shooting in scope. So I want to try my hand at it, and I think I have a story that warrants it. We’ll see if the universe aligns in order for me to make it. I don’t know. But I’m not scared of it because I know what the story is. If they’ll just let me make the story, then things will be alright.

***

The Bikeriders is now playing in movie theaters.