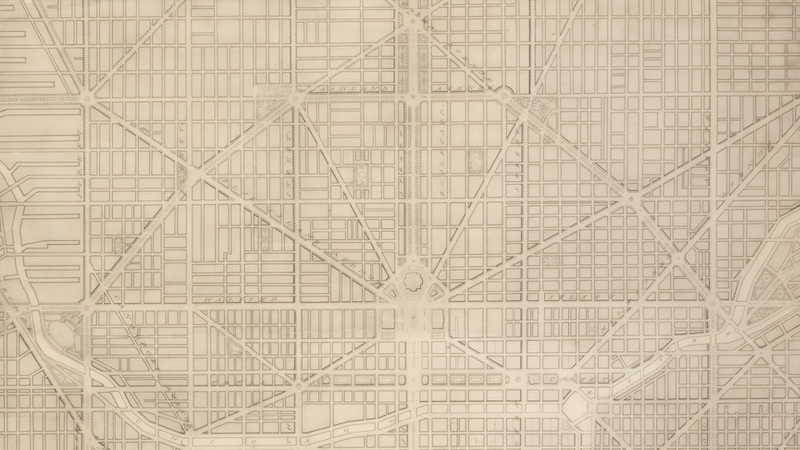

Three years after making his French filmmaking debut with The Truth — which, ironically, premiered in Venice — Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda is back in Cannes in a big way with the competition entry Broker, his first fully Korean film.

A master of the delicate family drama, Kore-eda’s last Cannes contender, 2018’s Shoplifters, won the Palme d’Or and went on to be nominated for an Oscar. Kore-eda describes Broker as a companion piece to Shoplifters, with the two films sharing a thematic interest in social outcasts who come together to form unconventional families.

The film features one of the starriest Korean ensembles of recent memory: The great Song Kang-ho (Parasite), Doona Bae (The Host), K-pop megastar turned actress Lee Ji-eun (also known by her stage name IU) and popular leading man Gang Dong-won (Peninsula).

Broker‘s story revolves around the anonymous adoption system — common in Korea and Japan — known as the baby box: a heated space, typically located outside hospitals or churches, where new mothers can leave unwanted babies to be safely adopted. Song and Gang play two down-and-out men who work for a baby box facility while secretly hustling on the side to sell some of the infants to Korean couples desperate for a child. Lee plays So-young, a desperate young mother who drops her newborn at the duo’s box, while a pair of police detectives, Bae and relative newcomer Lee Joo Young, surveil the facility in hopes of securing conclusive evidence to wrap up a long-running investigation. Brought together by chance thanks to the baby box, the five individuals embark on an unusual and unexpected journey across South Korea.

Produced and sold by South Korea’s CJ Entertainment, the film was picked up by Neon for North American distribution in one of the biggest pre-market deals of Cannes 2022.

Kore-eda, 59, widely considered the heir apparent to Japan’s great tradition of humanist cinema, spoke with THR in Tokyo ahead of Cannes about the making and subtle meanings of Broker.

What was the creative starting point for this film?

Well, in the process of researching my film Like Father, Like Son (the winner of Cannes’ Jury Prize in 2013 that centers on two children switched at birth), I was looking into adoption in Japan, and I came across this baby box operated by a hospital in Kumamoto, Japan. That was the very beginning of the idea. I began thinking that one day I would like to do a film that deals with this idea of the baby box. I also learned that in South Korea there were similar facilities and that the number of children given to them was much larger there. Later, around 2015, I got into talks with some South Korean actors about doing a film together one day, and that’s when I first began to think about putting the two ideas together.

Broker shares many themes with Shoplifters, particularly the notion of a group of social outcasts, even criminals, who come together to form an unconventional family for a time. What interested you about revisiting these themes, and in what ways did you want to take them in a new direction with Broker?

Well, actually, I developed the plot for Shoplifters and Broker at the same time, and I view the two films as siblings.

Back when I was doing my research for Like Father, Like Son, my understanding of parenthood was that women, when they have children, come to feel that they have become mothers almost automatically, whereas men seem to require a certain rationale for the new reality of fatherhood to really sink in.

This was my thinking back then and that’s how I was often discussing it, but then I was approached by a female friend who said to me, “No, it’s the same for women — not all women have this instant feeling of motherhood. The idea that maternity is something innate is a male prejudice.” I realized that, absolutely, this must be the case — and I felt really remorseful.

So with Shoplifters, you have the character Nobuyo (played by Sakura Ando), who, although she doesn’t have children of her own, tries to become a mother to the kids in that film. In Broker, you have So-young (Lee Ji-eun), who tries to protect her baby by abandoning it and choosing not to become a mother. Of course, there’s a hidden, very complex motivation behind that. But in any case, these two stories, exploring almost opposite sides of motherhood, came to me at the same time.

One of the other differences between the two is that in Shoplifters society’s intolerance is highlighted by the police and court system ultimately breaking up the ad hoc family, whereas in Broker, we are presented with a pair of police officers who ultimately become empathetic. What were your intentions with regards to this difference?

Well, you’re right, that is a crucial difference. In Broker, we have the detective Soo-jin played by Doona Bae, who says at the very beginning of the film, if you’re going to abandon your baby, you shouldn’t have it to begin with. And I think that is a sentiment that is shared by many in Japan and South Korea — this somewhat critical way of seeing mothers who give up their babies. So that’s where the character of Soo-jin starts. For me, one of the central movements of the film is following how much Soo-jin’s perspective can change as she goes on this journey. If the audience’s perspective can change along with her over the course of two hours, then I thought the film would be successful.

Forgive me in advance for this longwinded question… So, Broker, like your beautiful film After the Storm (2016) as well as Shoplifters (2018), builds dramatically towards a shared moment among the characters that has a very special quality — it’s the experience of a shared moment in time that can’t possibly last, but nonetheless is suffused with meaning for the time that it does. It’s something very delicate to try to capture in a film, and I’m not even sure what to call it, because it seems to be both a storytelling devise and an expression of values — or even a depiction of how people construct meaning together, in an existentialist sense. It’s those moments when time elongates and relationships deepen. In After the Storm it’s quite explicit, because that delicate moment is marked by the passing of the storm. But it’s also central to the dramatic movement of Shoplifters and Broker. I’m curious how you discovered this quality for your filmmaking.

Well, thank you for saying all that. With Broker, at which moment in the film did you experience this feeling the most?

I guess it builds gradually? It becomes palpable in the sequences where they are traveling in the van together, and then it sort of accumulates momentum until that scene when the characters are in the hotel room together, where Lee Ji-eun’s character, So-young, says those wonderful things to the other characters, expressing her appreciation of them by thanking them for being born. That’s where it crescendoed for me.

Well great, because that’s exactly the structure I tried to write (laughs). Certainly, that scene in the hotel is a very delicate, transient moment — and it’s a moment that is never going to happen again. That’s why it’s so important. I guess in every film, I want there to be a moment where life is celebrated. In this film, perhaps it’s just somewhat more explicitly shown.

It’s such a unique quality of your work, so I’m just curious how you discovered it. Is it a quality of experience that you recognized in your own life and tried to recreate, or did it come to you more intuitively? How did it become a part of your filmmaking?

I really don’t know…

(At this point in the interview, Kore-eda rubs his brow and pauses for a long, increasingly uncomfortable period of time).

Honestly, I rarely talk about my films in this way — especially discussing the qualities that are apparent across my different films. I would say that creating a scene like this is not something that’s so intentional — it’s not like I say to myself, yes, I’m going to capture this. Instead, it’s more like I have these characters and I’m on a journey with them, and I ask myself, what can I do while I have this time with them? In this way, I would say So-young is celebrating life on behalf of me. It’s kind of like Fellini. If you recall, all of the characters in his films, even if they’re not particularly good people, even if they are somewhat bad people who are kind of vulgar in some way, their lives are celebrated by their director. I love that spirit in his films. But I realize I’m now trying to get out of your question by discussing other directors… I’m just not sure what to say.

Okay, let’s talk about another great artist. Song Kang-ho is so wonderful in this film, as he so often is. What characteristics does he ever have as an actor that made you want to work with him, and what was your collaboration like?

I agree that he’s just incredible in every film that he does. The way he’s able to totally intertwines his characters’ good and evil traits is one thing I would highlight. And then there’s a lightness to all of his expression, which I find to be very appealing. It never becomes too heavy with him.

As for what it was like working together, on every take, it would feel as if he was doing it for the very first time, which simply amazed me. It’s really incredible to watch him work.

It’s hard to single out other performances, because the whole ensemble in this film is so fantastic. But what can you share about Lee Ji-eun, aka IU? She plays a rather gritty character, quite against her public persona as a pop star, yet she’s totally convincing.

During COVID, when I was staying home, a friend recommended I check out the Korean TV series, My Mister (2018), and I completely fell in love with Lee Ji-eun’s acting. It was simply superb. After that, she was the only actress I could imagine for this role. What’s especially remarkable about her is her voice and the way she’s able to express herself vocally. In Japanese, you have a word and the crisp meaning of that word — but she’s able to exude something additional that kind of seeps out from the language, even when there’s nothing to vocalize, in the pauses before and after words. She’s brings such a richness to the dialog. Obviously, all of the lines were things I wrote myself, but it would feel like I was listening to music or poetry, because of the surprising way she vocalizes everything.

The film presents a variety of points of views on the baby box adoption system. Some characters are quite critical of it, but on the flip side, the film demonstrates how a loving family can be made from almost any set of conditions if the people coming together around the child have the right intentions. Did you come away from your research and artistic interrogation of this topic with any particular view on this adoption system?

Well, it’s not that I gained a new perspective with regards to adoption from having made this film. But having done this research, looking at the various things that happen around these baby boxes and researching the lives of children who were given up for various reasons and grew up in these childcare facilities, I came to understand that these children grow up asking themselves a fundamental question, which is: Is it okay that I was born? Was I supposed to have been born? You know, coming into contact with that kind of hardship really makes you think deeply. I felt a strong sense of responsibility about how I was going to clearly express my thoughts in response to this — all of which led me to that scene in the hotel room. I was thinking, what do I want to say with this film to the people who grew up with this experience? I molded all of my thoughts around how I would express my answer to them, and I think that’s the strongest perspective that’s in the film.

You’ve written all your films yourself. What is your writing process is like?

Well, it’s almost like I’m writing as I shoot the film. Obviously, for this film, I had the initial draft, which I wrote during prep. But what happens after the two characters go to Seoul — what their actions would be, where the story would end — is something that I left totally open. I didn’t have a shooting script for that until the very last minute, after the crew came to me and said, we need to finalize this because we need to make sure that we can find a location for it.

As I was filming — thinking, what will Sang-hyeon (Song Kang-ho’s character) do, and how can I make So-young unhappy? — I kept searching for the answer and I rewote the screenplay many times. Each time, I would show it to Song Kang-ho and it was this constant to and fro between us, sharing ideas back and forth, until finally we landed on the ending. Obviously, making a film this way is physically very challenging and hard on everybody. But to be able to come together and collaborate in that way and to finally find an answer — there’s just no better or more fun style of filmmaking than that.

I’m curious about the title. It’s not “Mother” or “Adoption,” but Broker. What were you trying to signify with the title?

Until half-way through, I called the film by its tentative title Baby, Box, Broker — three words beginning with the letter B — and I thought the story was about connecting them. But as I was writing, I realized that [the film] had this structure where it’s the detective’s side, Soo-jin’s side, that ultimately wants the baby to be sold the most. The “broker” in the film changes as the story unfolds. When I understood that, I found that to be a really intriguing idea. And I thought by focusing on the word Broker, the title would become very simple and very strong. I really liked this structure where the person wanting to sell the baby inverts as the storytelling progresses.

You’re very much a regular at this festival — part of the Cannes family, as Thierry Frémaux would say. Do you have any special memories here?

It’s a special place and I’ve been there eight times, I think. I don’t know if I’m family, but I’m almost starting to feel slightly apologetic for being invited so many times. (Laughs) But when I go to Cannes, it makes me realize how truly beautiful filmmaking, which is my livelihood, is. The feeling of being connected to the world through cinema leads me to want to make another film. It’s a place where magic is cast. It has nothing to do with winning awards or not. It’s like you go there to be enchanted — and you return galvanized. That special encounter happens. Cannes is a place where you can re-encounter cinema. That’s what I think it is. But maybe I’m tying up this conversation too neatly!