The setting and subject of Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s second film couldn’t be more different from those of her first. But the contemporary drama The Mustang and the director’s interpretation of D.H. Lawrence’s century-old novel share a sensuous physicality, an appreciation for skin and muscle — how bodies move, how they spar, how they intertwine. In the 2019 film, the beautiful bodies belong to Matthias Schoenaerts and a wild horse; in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Emma Corrin and Jack O’Connell steam up the screen as kindred spirits ignited by carnal passion.

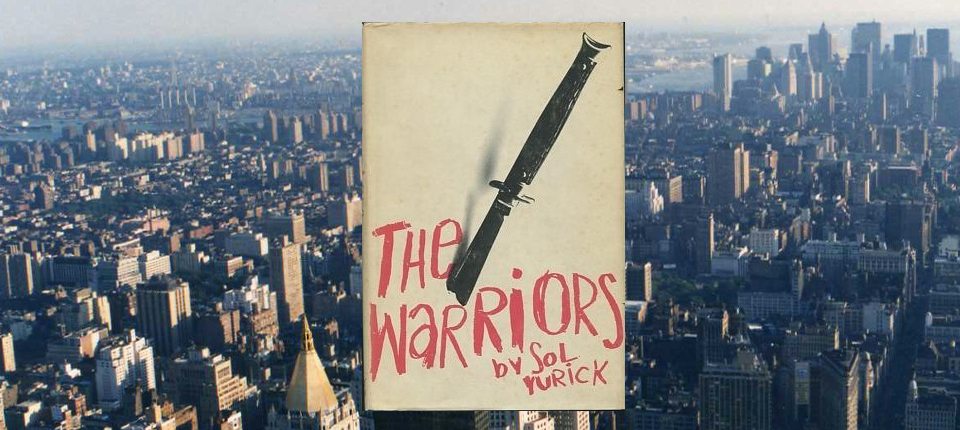

Lawrence was dismissed as a pornographer by many, and his oft-adapted 1928 novel, his last, was for years banned as obscene in several countries. Then it became part of the English-lit canon. Eventually it would be dissed by Susan Sontag as reactionary. Even in this telling, where the intelligence of Corrin’s character and her drive for honest experience form the narrative engine, placing the spotlight on the woman behind “milady,” there’s something old-fashioned about the all-encompassing romance — satisfyingly so.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

The Bottom Line

Sharp, streamlined and sensuous.

The movie, which Netflix will bring to theaters in November and to its streaming service the following month, is true to Lawrence’s idealization of sex and nature, in invigorating ways. Screenwriter David Magee, whose screenplay for Life of Pi sapped the magic from an entrancing novel, and whose Finding Neverland script veered between overstatement and inertia, finds his groove here with a smart streamlining of the source material that accentuates the positive while maintaining the book’s observations about class and, above all, sensuality.

Corrin, who uses they/them pronouns, is known for their turn as Princess Diana on The Crown, and brings an exultant modernity to their first major lead role in a film. That’s perfectly in sync with a story that unfolds at a moment when Edwardian mores are dying, and whose central characters are leaping into the new age. O’Connell embodies a more refined and cerebral version of the title character, gamekeeper Oliver Mellors, than seen in many previous adaptations. Together the actors create a relationship that’s tender and thoughtful as well as voluptuous — true to Lawrence’s idea of harmony between mind and body, “a proper reverence for sex, and a proper awe of the body’s strange experience.”

The movie opens during World War I, as newlyweds Constance Reid (Corrin) and Sir Clifford Chatterley (Matthew Duckett) prepare for his return to the front. In short order he’s back home, his battle injuries leaving him paralyzed from the waist down and turning his bride, who’s at first willing, into his only caretaker at Wragby, his estate in the Midlands. They had discussed children on their wedding night, and neither was particularly gung-ho, but now, with Clifford impotent and the matter of the family legacy brought into sharp relief, he suggests that she find someone else to impregnate her, and they’ll raise the child as theirs. Modern!

In frocks to die for (designed by Emma Fryer) and in her every gesture, the strikingly self-possessed Connie blends a bohemian sensibility with her new status as the wife of a wealthy man. She’s not blinded by comforts, though, and alarm bells ring loud and clear at the first signs of Clifford’s clingy, controlling nature (though in that regard he has nothing on the central character of Él, a 1953 Luis Buñuel film that screened in Telluride this year). Those signs revolve around the alarming words “I’d be lost without you,” what you might call a threat disguised as gratitude. Beyond that, just as his wife is embracing life with all that’s in her, he expresses a certain nihilism and, worse than that, a heartless capitalist impulse when it comes to modernizing his family’s mines, his eye on efficiency but with no particular regard for the miners.

The helmer, working again with The Mustang’s editor, Géraldine Mangenot, certainly stacks the deck; it’s clear from the get-go that Clifford is Not the One for Connie, however devoted she may be, however eagerly she types his novel and does her hopeful best to adjust to their situation. She assures her skeptical sister, Hilda (Faye Marsay), that her groom is progressive — and so he turns out to be, to a point, with his unorthodox suggestion for how to build a family. He, um, plants a seed, and the lustiness with which it blossoms once Lady Chatterley meets Mellors startles the characters but makes perfect sense.

O’Connell (Seberg) conveys how gun-shy the gamekeeper is, having returned from his stint as an army officer to a marriage in tatters. He lives a solitary life in his stone cottage on the estate, reading Joyce and breeding pheasants (symbolism not to be ignored). In a beautifully played scene, Connie holds a days-old chick in her hands and is overcome by emotion. From there, it’s off to the races, and frequent, rapturous rendezvous in the woods.

Too many sex scenes in contemporary movies feel gratuitous in narrative terms or rote; here, the director and her actors strike chords of intense, unabashed mutual discovery, and Benoît Delhomme’s kinetic camerawork, with its exhilarated forward momentum, is attuned to the sparks, whether the setting is the lush grounds of Wragby or the interiors of Karen Wakefield’s strong but unshowy production design. (The feature was shot in England, Wales and Italy.) The score by Isabella Summers (keyboardist with Florence and the Machine) enriches the love story with its rise and clash of strings and its melodic passages.

As to the people around Lady Chatterley, Mrs. Bolton, the caretaker who eventually relieves Connie of her nursemaid duties, still talks about her miner husband’s cruel death a quarter-century earlier, as if it were last month. She’s played by Joely Richardson, who portrayed Lady Chatterley in Ken Russell’s 1993 BBC miniseries. Here she’s subtle and moving as someone clinging to the past and, presumably, to social convention. When push comes to shove, though, Mrs. Bolton upends expectations, in contrast to Mrs. Flint (Ella Hunt), the schoolteacher who eagerly befriends Lady Chatterley but can’t get past notions of middle-class respectability when rumors about Connie and Mellors start circulating.

No less than love and sex, courage is at the core of this iteration of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Secretly, Connie and Mellors, each still married to someone else, forge a partnership of equals — beyond their class distinctions, beyond their roles as man and woman. It’s the most idealistic notion in the story. “Are you afraid?” Connie asks Mellors soon after they’ve begun. “I bloody well am,” he says, without a moment’s hesitation. Lady Chatterley has met her match.