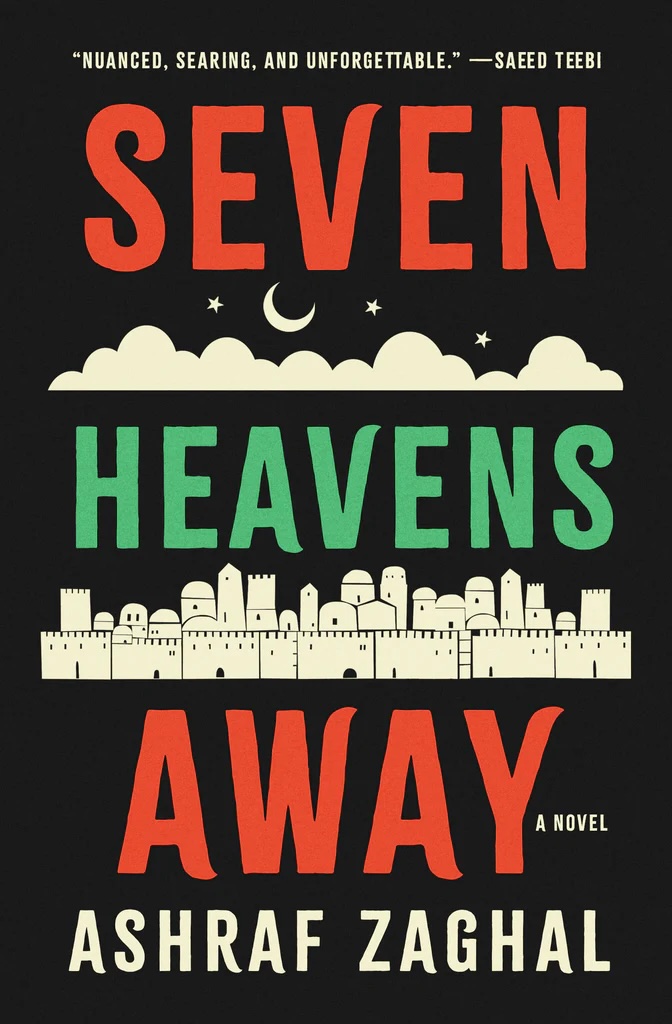

One of the finest Japanese independent films of the past few years is finally landing in U.S. cinemas this weekend. Second-time director Kei Chika-ura’s Great Absence, which debuted to strong reviews at the 2023 Toronto Film Festival and later won the best actor prize in San Sebastian for its star, Japanese screen icon Tatsuya Fuji (In the Realm of the Senses), opens in New York on Friday and Los Angeles on July 26, with a nationwide rollout to follow.

Great Absence centers on Takashi (Mirai Moriyama), an ambitious stage and screen actor, who is drawn back into the orbit of his estranged father (Fuji) by a jarring phone call from the police. His father’s second wife is missing and the old man, once an esteemed physics professor, appears to be suffering from the latter stages of acute dementia. Takashi, with his new wife (Yoko Maki) by his side, swiftly decamps to his father’s home on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, and there the film transitions into the mode of a beguiling and heartbreaking mystery, as the young man gradually grasps what has become of his long-absent father’s wife and life.

As the film’s official summary elegantly puts it: “At a certain point in life we often have to deal with a past that was thought to be forgotten, lost forever, and which instead resurfaces, with all the emotional awkwardness generated by unwanted absences, memory lapses, and the missing pieces of the puzzle of our existence.”

Acclaimed Japanese cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki (best known for his work with arthouse favorites Hirokazu Kore-eda and Naomi Kawase) shot Great Absence on 35mm film stock with mostly classic, fixed camera set-ups, lending the story’s elegant transitions from flashbacks to the present day all of the richness and gravitas of jumbled but vivid memory.

Ahead of Great Absence‘s U.S. premiere, The Hollywood Reporter connected with Chika-ura via Zoom to discuss the film’s deeply personal roots and its implicit commentary on the changing nature of marriage roles in Japan.

Tell me about the creative genesis of Great Absence.

Well, I have to go back to my debut feature, Complicity. It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2018, but since it was an independent film, I had some difficulty finding a distributor in Japan, so it didn’t release in my country until 2020. By that time, I had already written an entire script for my second feature and I was all ready to go into production. But then the world stopped because of COVID-19, and around the same time I received a phone call from the police in Fukuoka telling me that my father was being “protected.” They didn’t say he had been arrested; they said he was under protection. I was shocked and didn’t understand what this meant. What actually happened was that my father had placed a distress call, saying that he and his wife were being held hostage by a man with a gun. Of course, this wasn’t true. My father had begun to suffer from acute dementia — and I had no idea. I was totally surprised, because my father was a retired university professor, and although I didn’t like him so much, by all appearances he was a very reliable member of society. Everyone who lived around his house was really upset because a huge number of armed police officers had stormed the neighborhood in response to his emergency call. It was a big incident. I immediately boarded a bullet train and traveled from Tokyo to Fukuoka [on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu], and I then started making monthly trips to spend time with him. Reflecting on all of the paralyzing experiences of the pandemic, as well as my personal crisis with my father, I decided to abandon the project I was ready to shoot. I needed to write something that resonated with my current mindset as well as what the whole world was going through. It’s a fictional film, but it was very much inspired by my own experience with my father.

Was the film you abandoned something totally different? What was it like?

Yeah, it was very different. It was a genre film, a mystery movie. But Great Absence also has some mystery movie elements, so maybe I carried some of that over.

Aside from that inciting incident, in what ways did you draw on your own experience during the writing and creation of Great Absence?

One thing is the protagonist’s personality. He’s a very restrained person and doesn’t like to express his feelings — and that’s basically the way I am. When I first discussed the role of Takuya with Mirai Moriyama, he said he didn’t really understand what was going on in the film, because the character expresses no clear motivation and there’s no clear emotional movement. He wasn’t really sure how he would play the character. I told him that Takuya is basically based on my personality — and Moriyama started to observe and study me, and I think this helped him figured out how to inhabit the protagonist. Moriyama is a very unique actor in Japan. Aside from the many films he’s been in, he’s very well known as a stage actor and a contemporary dancer. But due to his extraordinary physicality, he’s often asked to play eccentric roles in Japanese films. So I was really excited to see him act in a very controlled, restrained way, and I think he gave an excellent performance.

In Japan and other countries with aging populations, coping with dementia, either firsthand or via a loved one, is becoming an increasingly universal experience. But as I watched the film, I wondered whether you might be striving towards a more general form of universality as well. The circumstances your character finds himself in are quite extreme (he’s been estranged from his dad for 20 years), but I found myself relating to the film’s central mystery nonetheless — that somewhat uncanny question of who your parents really are, or were, as people, and being forced to reassess the whole sweep of their lives as they approach the final chapter.

That’s a very interesting perspective. It calls to mind a scene in the film for me — the third confrontation between the father and son in the care facility. This is the scene where the father pleads with the son to forgive him. The son doesn’t want to, but eventually he gives in and says, “Okay, I forgive you.” Some viewers interpreted this as their reconciliation. For me, it wasn’t a reconciliation; it was an inversion of their relationship — of protector and protected. Shortly after this, in a very symbolic moment, the son gives his father his belt and helps him put it on. So, this film is a mystery — and it’s also about the roles of husbands and wives in Japan — but on an important level, it’s a story about a man becoming a grownup and growing beyond his father.

Was making this film part of that process for you?

Well, the reason I love cinema is all about my father. My father took me to the theater every weekend of my childhood. I grew up in West Berlin, before the fall of the wall in 1989, because that’s where my father was working. As I was growing up, my father always told me that the very first film I saw in the theater was Every Man for Himself by Jean Luc Godard.

Wow, that is not a kids’ movie…

(Laughs.) Yeah, I was just four or five years old, so I don’t remember it at all. But these were the kinds of films he would take me to, and he always reminded me that this was the first one I ever saw in a cinema. So this became a very important fact for me. But it was not a memory in my mind or heart. It only really existed in his mind — and by 2020 his mind was fading. So amidst this crisis, I thought that I needed to take the true meaning of this memory over — into my body. That’s a very abstract thought, but it’s the real reason I felt I had to make this film before I could go on to other projects.

Japanese screen icon Tatsuya Fuji in his award-winning performance as the deteriorating patriarch in ‘Great Absence.’

You mentioned that Great Absence is also a story about the changing nature of marriage in Japanese society.

Well, with the relationship between the father and his wife, Naomi, I’m portraying the older generation, where the woman stepped behind the man and her life was all about supporting her husband. My parents were exactly like that. With this story, I tried to free Naomi — to let her find her own way for the remainder of her life. But it’s not only about her personal journey, I also wanted to express my hope for a more ideal situation between Japanese men and women. The younger couple reflects the current situation for Japanese men and women. It’s flat, there’s no hierarchy, and they see and support each other.

So, I have to ask you about casting and collaborating with Tatsuya Fuji. He’s had such an amazing career. Why did want him for this part and how would you describe the nature of your collaboration?

Fuji is undoubtedly one of Japan’s legendary actors and I have a deep admiration for his work — especially the films he made with Nagisa Oshima in 1970s. Ever since I began making my first short films, I had the dream of creating a feature that could be considered one of Fuji’s signature works. And you know, for this film, he won the best actor award at the San Sebastian Film Festival last year. So I’m glad that I can say that I achieved one of my biggest dreams as a filmmaker. I didn’t cast him for this film. Rather, I made this entire film simply in order to work with him. I wanted to be a part of his history. And what’s it like to work with him? He’s always great. I don’t direct him on set at all. I do nothing. He’s just there. He shows up and he delivers — as you saw in the film. That’s our relationship. It’s all about mutual trust.

Kei Chika-ura