Nope, Jordan Peele’s latest offering, slinks and slithers from the clutches of snap judgement. It avoids the comfort of tidy conclusions, too. This elusive third feature from the director of Get Out and Us peacocks its ambitions (and budget) while indulging in narrative tangents and detours. It is sprawling and vigorous. Depending on your appetite for the heady and sonorous, it will either feel frustratingly perplexing or strike you as a work of unquestionable genius.

This is, undoubtedly, Peele’s effect. Since his canonical social thriller Get Out, the director has proven himself unafraid of his own imagination. His films are grand in scope, enigmatic in meaning and rarely boring. Their cool frames are buttressed by the director’s enthusiastic, genre-fan eye. Peele loves a good time, and his films are like Gatsby-esque soirées for enjoyment-starved audiences.

Nope

The Bottom Line

As fun as it is ambitious.

Even when parts of it don’t gel, Nope is a rapturous watch. This film, about a pair of sibling horse wranglers who encounter an uncanny force on their ranch, covers a wide range of themes: Hollywood’s obsession with and addiction to spectacle, the United States’ inurement to violence, the siren call of capitalism, the legacy of the Black cowboy and the myth of the American West. Aided by a strong cast, led impressively by Daniel Kaluuya, Keke Palmer, Steven Yeun and Brandon Perea, Peele plunges us into a cavernous, twisted reality.

Agua Dulce is a serene tract of Southern California, where large, billowy clouds appear to caress the tips of sandy, burnt-orange mountains. It’s also home to Otis Haywood Jr. (Kaluuya), or O.J. for short, and his father (Keith David). The two men spend their days caring for their stable of mares and stallions and running Haywood Hollywood Horses, the oldest Black-owned horse training service in the industry. After his father dies in a strange accident, O.J., a quiet wrangler, reunites with his estranged sister Emerald (Palmer), or Em, to inherit the business.

Nope opens with a brief introduction of the senior Haywood’s death before moving on to the sibling reunion. With their father gone, O.J. and Em must take over existing contracts. Whereas his dad dressed the part of a cowboy, O.J. prefers a more unassuming outfit of plain shirts, jeans and a Carhartt cap. And unlike his sister, he possesses no charisma or desire to be seen. On the set of one production, the introverted O.J. stands close to his horse, eyes glued to the floor, waiting for Em. Kaluuya does wonders with a character who primarily communicates through stares. His penetrating eyes are impressive in their emotional range, and his looks begin to feel like a secret language.

Em arrives to the shoot late, but her energy is infectious. She loves the spotlight and hungers for easy routes to fame. Most of the on-set crew are immediately taken by her boisterous energy, her toothy grin and talk-show-host delivery of fun facts: Did you know that the Haywoods are the direct descendants of the unnamed Black jockey in Eadweard Muybridge’s 1878 The Race Horse, the first film ever made? Now you do.

Behind Em stands a tortured O.J., gripping the reigns of his horse. In a later scene, he admonishes Em for her style, for promoting her multihyphenate career (actor-singer-stuntperson). Em reminds him that running the ranch is her side gig, not her dream. The Haywood siblings’ relationship bears obvious scars of past wounds, but Peele shortchanges audiences when it comes to why. Their suspicious communication style establishes their inability to work as a team, but the characters themselves would have benefited from greater depth and dimension. Kaluuya and an equally impressive Palmer wring as much as they can from O.J. and Em, but they needed another scene or two to burrow into the precipitating events of their fractured relationship.

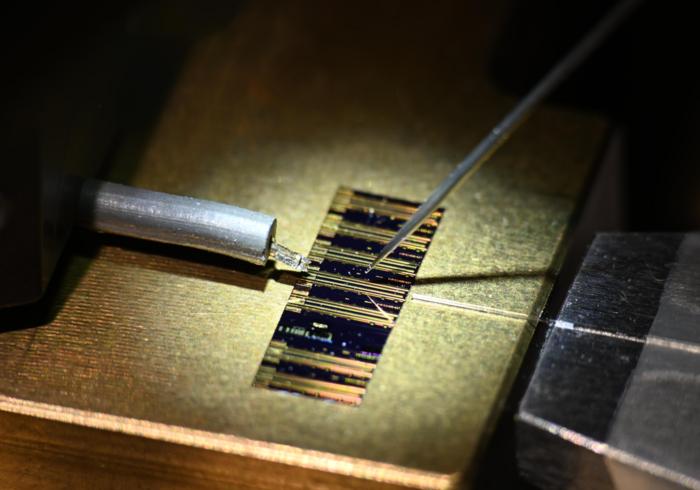

What Peele prioritizes, and excels at, is showing the eerie occurrences on the Haywood Ranch and the Gold Rush-themed park a short drive away. The latter is run by Ricky “Jupe” Park (Yeun), a former child star who witnessed a traumatic event on the set of his show. Instead of wallowing in the past, Jupe, like any successful American, has found ways to monetize his pain. His path from being exploited by the industry to exploiting himself is a fascinating thread of Nope, which functions most confidently as an allegorical tale about Hollywood and its thirst for spectacle — a kind of contemporary riff on Sodom and Gomorrah.

When O.J. and Em begin piecing together why strange things have been happening on their ranch, their instinct is to make money off it. In their attempts to “capture the impossible,” they meet Angel Torres (Brandon Perea), a recently heartbroken employee at a big-box electronics chain. (Watching the three work together, brainstorming and testing strategies, may bring to mind the teamwork of the characters played by Sidney Poitier, Henry Belafonte and Ruby Dee in the 1972 film Buck and the Preacher, which inverted Hollywood’s tradition of the Western by casting Black actors in the main roles.) A late, and unlikely, addition to this rag-tag crew is Antlers Host (Michael Wincott), a cantankerous and revered cinematographer. Although their individual motivations seem different, each of them is driven by a desire for money, fame or some combination of both.

Peele has assembled a first-rate cast, and the results are electric. Whatever shortcomings the screenplay may have in fleshing out their characters, Kaluuya, Palmer, Perea, Yeun and Wincott deliver memorable turns, successfully balancing Nope’s comedic notes with its more haunting, suspenseful overall mood. Hoyte van Hoytema’s engulfing cinematography and Michael Abels’ pulsating score help sustain the film right up through its transfixing end. It won’t be to everyone’s taste, but Nope offers up a glutton’s feast for Peele disciples and fans of brainy sci-fi thrillers, ushering the director into an intriguing new phase of cinema that’s as rhapsodic as it is demanding.