In the 2018 Korean drama My Mister, Lee Sun-kyun stars as a man who seems to have it all – a stable career, the respect of his colleagues and a loving family – but is in actuality burdened by the pressures of providing for his loved ones and employees while navigating an extortion scheme and suspicions of a workplace affair. Beset with a melancholic disposition, at one point he stumbles on some train tracks and contemplates remaining there. It’s a fleeting thought but a poignant moment in the critically acclaimed series, which won Best Drama at the Baeksang Arts Awards and was a highlight in Lee’s notable career.

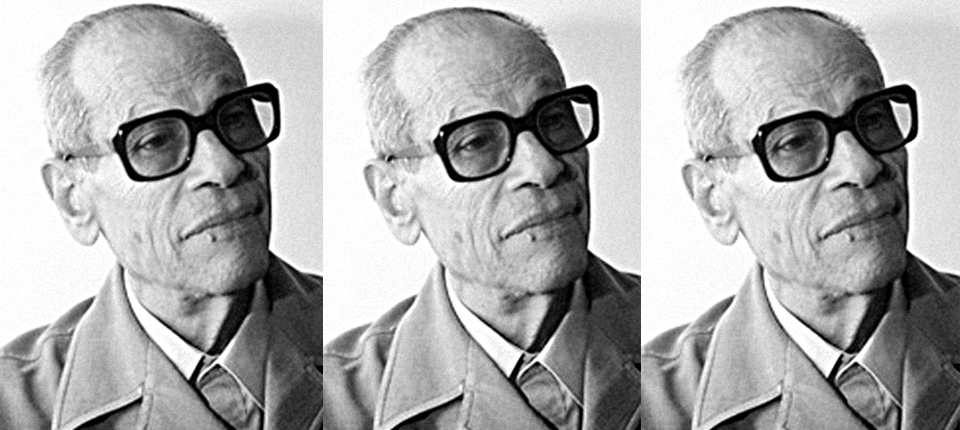

That Lee – one of Korea’s most popular actors who earned worldwide mainstream recognition through Parasite – would be involved in any sort of real-life scandal was nearly unthinkable. He had been married (to actress Jeon Hye-jin) almost as long as he’d been famous, with two sons and a wholesome reputation – exactly in line with what Korean society demands of its celebrities. But in October, news broke that he was under investigation for recreational drug use, which is illegal in Korea. Over the past two months, he submitted to police questioning three times as every detail of the case, which grew to include leaked conversations with an escort and a counterclaim from Lee that he was deceived into taking illegal drugs and was being blackmailed, was breathlessly dissected in the news and on social media. And three days after he was released from his third interrogation – which lasted 19 hours ending on Christmas Eve – Lee was found dead in his car in an apparent suicide.

His death has put a spotlight on Korea’s current political and social climate, with potential ramifications for the country’s status as a global soft superpower. In April, conservative president Yoon Suk Yeol, who was elected in May 2022 and has been compared by his opponents to Donald Trump, declared a “war on drugs,” whose usage already is highly stigmatized in Korean culture. While police booked a record-high 17,152 people on drug-related offenses in 2023 – up 38.5 percent from the year before – it was the accused entertainers who naturally drew the most attention, often at the encouragement of or at least enablement by law enforcement officials. Lee was being investigated as part of a probe of eight individuals, but his was the name leading the headlines.

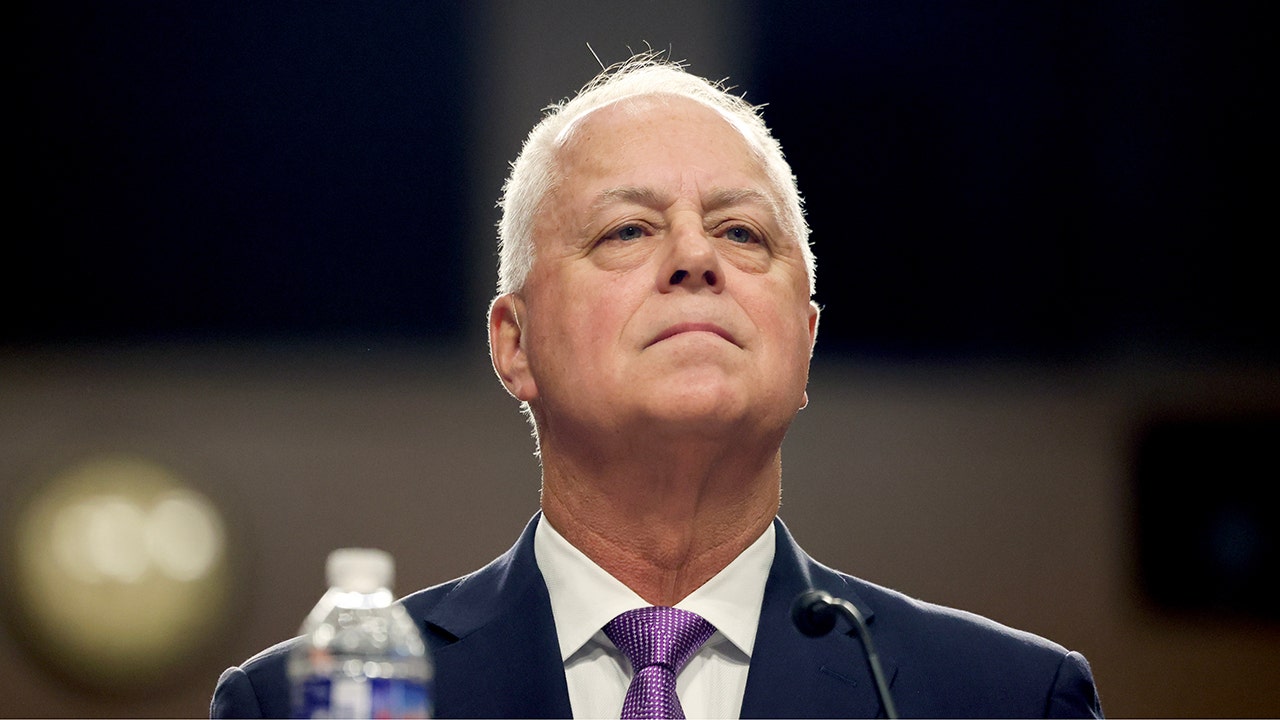

Each time he was summoned to the police station he stood on the photo line, a Korean convention in which a suspect or person of interest faces cameras and questions from the press before or after going inside. “The practice, with no legal grounding, has caused a public stir of late over the prosecution allegedly making use of it in order to embarrass and shame the suspects,” wrote The Korea Times adviser Park Moo-jong in a 2019 op-ed arguing that the procedure violated human rights. “Having suspects, especially big shots in society, stand at the photo line is not any different from leaking unconfirmed facts about suspected crimes that may help people have preconceptions.” After Lee’s death, police officials revealed that he had requested his third interrogation not be open to the press, and that the request was rejected.

In addition to heavy potential criminal penalties (ranging from six months to 14 years in prison), drug use also carries professional and social consequences in Korea. In the entertainment world, even mere accusations of untoward actions have caused the removal of K-pop idols from their groups, their existence never to be acknowledged again. As soon as news of Lee’s scandal broke in October, he withdrew from the drama series he had just begun to film.

That Lee would presumably take such a drastic measure in response to alleged marijuana and ketamine usage (as well as marital infidelity) may be hard to comprehend for people from a country where the former substance (although still disproportionately prosecuted among Black and brown Americans) is legal in many states and even made light of as part of “stoner culture,” and where celebrity affairs are generally treated as garden variety scandovals. But Korea has the highest per-capita suicide rate among developed countries (24.6 per 100,000 people), and its public figures are not immune: Former president Roh Moo-hyun killed himself in 2009 after accusations of bribery threatened to tarnish his legacy, while a number of K-pop artists have taken their own lives after public and private battles with depression, harassment and living under a high-pressure spotlight.

What’s unique about the shocking tragedy of Lee Sun-kyun is that it could pose a particular kind of reckoning for the myriad political and social factors that led to his death. Given his stature in the Korean entertainment industry and the Korean entertainment industry’s growing stature on the international stage, his fate could have a chilling effect on the perception of South Korea as a cultural and artistic mecca to be envied – and to do business with.

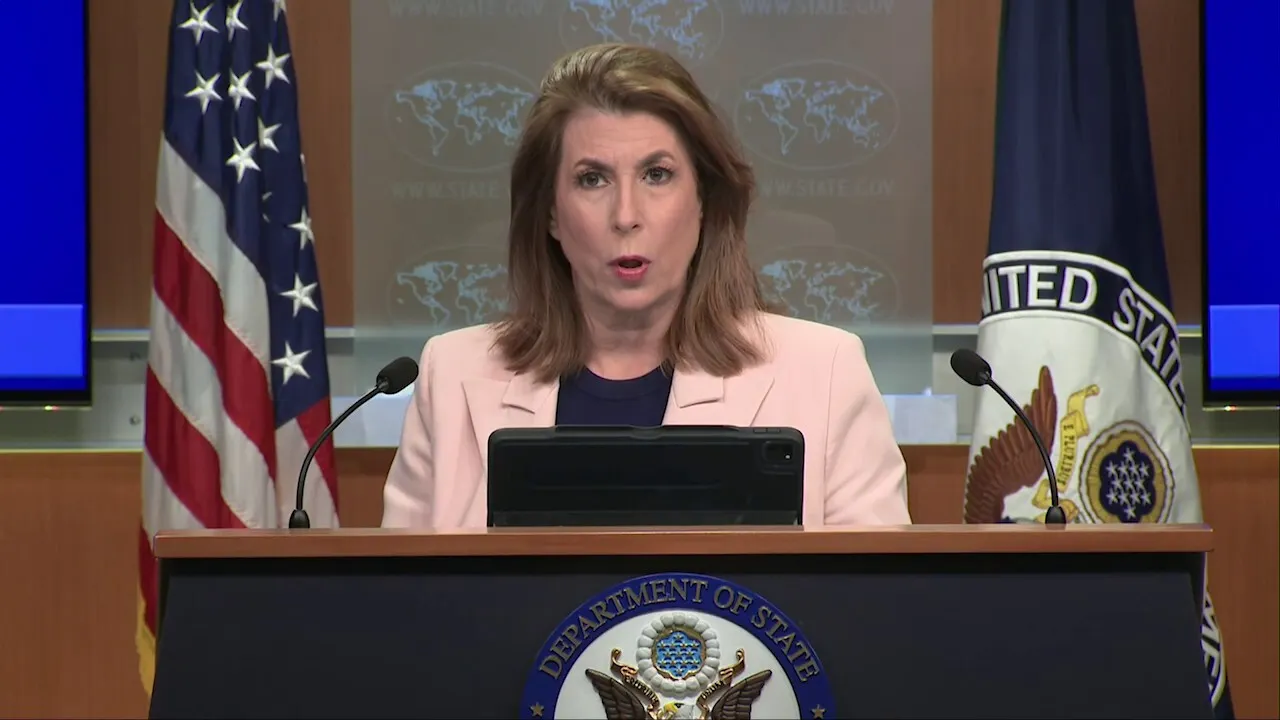

In April, President Yoon made a state visit to the U.S., where he met with top Netflix executives, including co-CEO Ted Sarandos. There, Netflix unveiled a plan to spend $2.5 billion to produce Korean content over the next four years. Disney, Apple and Amazon also have made sizeable investments in Korean content, with Lee himself starring in Apple TV+’s first Korean-language original series in 2021. In Hollywood, it takes a lot to bench an actor – think pre-Iron Man Robert Downey Jr.-levels of addiction or a Jonathan Majors assault conviction. (Meanwhile, if you’re Ezra Miller, your franchise job is still safe.) But when actor Yoo Ah-in (best known on the international film scene for starring opposite Steven Yeun in 2018’s Burning) tested positive for multiple drugs earlier this year, Netflix had to recast him for the second season of its supernatural drama Hellbound and pull back the 2023 releases of two more Korean projects he was set to star in, The Match and Goodbye Earth, which to date still are not available on the platform. The idea that a project could be derailed by an actor breaking a morality clause, and that accusations of doing so could lead to fatal consequences, could give Hollywood studios pause before doing further business with Korea.

But there are flickers of indications that Lee’s case could lead to some type of reform, prompted by scrutiny both abroad and at home. In the days since his death, international outlets including The New York Times, the BBC and CNN have published commentaries on Korea’s stringent drug policies as well as how law enforcement, the media and the public treat celebrities. Domestically, the Korean police found themselves having to defend their handling of Lee, particularly the lack of privacy he was afforded. And rather than being regarded as a pariah, to which Lee perhaps thought he would be consigned, the actor’s private memorial service was attended by A-list colleagues – including Parasite director Bong Joon-ho and Squid Game star Lee Jung-jae – while fans posted tributes to him outside the funeral home and online.

During Lee’s harrowing final two months of life, there was one other person who could perhaps relate. In October K-pop megastar G-Dragon was booked by police two days after Lee and also was subject to multiple drug tests, interrogations and trips to the photo line. But police closed his case earlier this month, citing insufficient evidence. In response, the iconoclastic artist announced he was spending 300 million won ($230,000) to launch a foundation to help fight drug abuse and treat addiction. It’s both a defiant move by G-Dragon and also a socially significant one, reminiscent of the late Matthew Perry’s work to destigmatize substance addiction by placing the emphasis on reframing the condition as a disease and aiding the afflicted.

If such efforts succeed, they could help reconcile Korea’s social mores with its cultural ambitions, creating a more stable terrain for its international commercial prospects and an environment where, if a talent finds himself in a situation like Lee Sun-kyun did, he could hope for a better outcome.

If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention hotline at 1-800-273-8255.

.jpg)