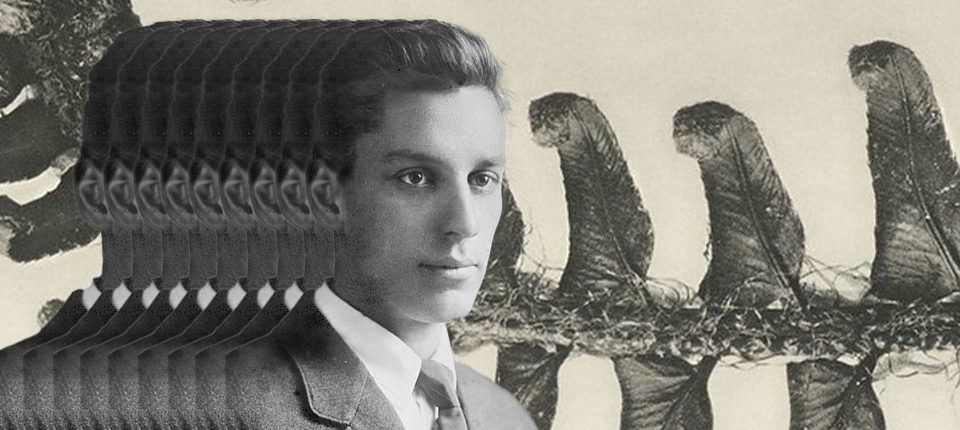

The poetic title, Afternoons of Solitude (Tardes de Soledad), might evoke tranquility and relaxation, maybe a few lazy hours in a hammock with a book. But don’t be deceived. Albert Serra’s transfixing portrait of 27-year-old Peruvian bullfighter Andrés Roca Rey, and of the hotly contentious Spanish tradition in which he has emerged as a star, never downplays the visceral brutality of what’s essentially blood sport as performance art. Anyone with a low threshold for cruelty to animals will find this a harrowing watch, but for those with the stomach for it, the doc is a unique study of discipline, bravado, laser focus and showmanship.

Serra, known for stripped-down slow-cinema narratives that can be both seductive and distancing, had something of an international breakthrough with 2022’s Pacifiction. This nonfiction detour evinces many qualities familiar from his dramatic features, among them the atmospheric, quasi-dream state; the long takes, usually from a fixed angle; the repetitions; the contemplative silences; the embrace of moral ambiguity. The picture screens in the New York Film Festival following its world premiere in competition at San Sebastian, where it won the festival’s top honor, the Golden Shell.

Afternoons of Solitude

The Bottom Line

A work of barbaric beauty.

Venue: New York Film Festival (Spotlight)

Director: Albert Serra

2 hours 3 minutes

Working again with cinematographer Artur Tort, Serra creates an immersive experience that effectively draws us in close to the stacked face-off between man and beast while casually considering — strictly through observation — the psyche of a taciturn subject. The film instantly positions itself as one of the most unflinching depictions of bullfighting ever made, admittedly a limited canon.

Pedro Almodóvar playfully explored the erotic allure of the torero and the intersection of sex and violence in 1986’s Matador, while Francesco Rosi weighed the spectacle of the corrida against its primal savagery in 1965’s The Moment of Truth. But the 1957 screen adaptation of The Sun Also Rises, by literature’s most famous bullfighting aficionado, Ernest Hemingway, was widely dismissed as a Hollywood blunder, including by its author. Hemingway’s 1932 book on the subject, Death in the Afternoon, may have partly inspired Serra’s title.

Animal welfare protestors have brought declining popularity to the traditional Spanish-style bullfight, but it remains legal in most of the country, as well as Portugal, Southern France, Mexico and much of South America. Its defenders insist that the corrida is not a sport, but an ancient ceremony rooted in proud national heritage — more fiesta than bloodbath. Serra ostensibly takes no position on the controversial nature of his subject, but the sharp detail of Tort’s images, with their blazing colors and graphic violence, seems destined to stir ongoing arguments.

The movie opens in what appears to be an arena holding pen with a tight shot of a bull, a magnificent creature with a gleaming black coat. Pacing in a state of agitation, its flanks heave with every breath and its mouth drips with saliva. As is perhaps suggested by the darkening mood of Marc Verdaguer and Ferran Font’s score, this is the only time in Afternoons of Solitude when we see one of the animals not charging at a matador in the ring or being lanced, speared with barbed darts called banderillas and ultimately felled by a sword embedded deep between its shoulder blades.

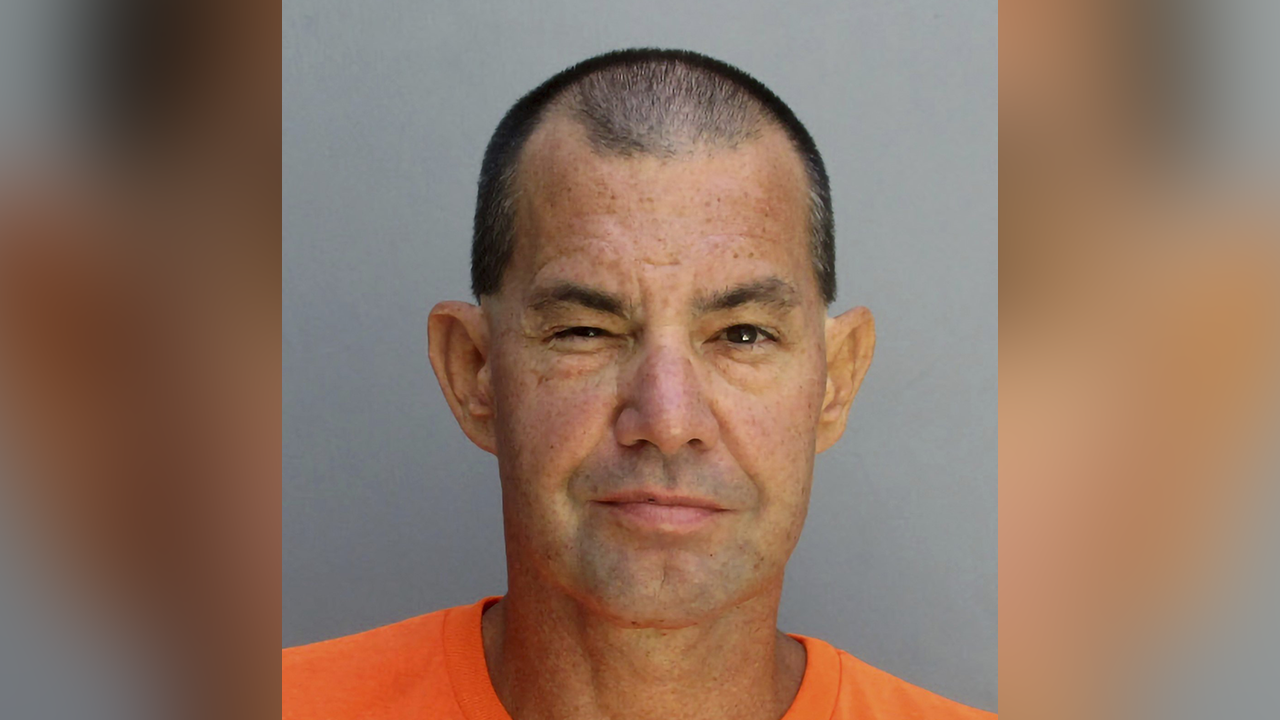

In one of the traveling sequences that regularly punctuate the doc, Roca Rey is introduced sweating profusely in a car on his way to an event in dazzling matador regalia. He remains mostly silent as his entourage, known as a cuadrilla, showers him with praise and encouragement. The amount of time these guys spend marveling at his gigantic set of balls indicates how intertwined bullfighting is with swaggering machismo.

The film incorporates extended footage from major bullfighting events in cities including Madrid, Seville and Bilbao. We watch Roca Rey perform pre-fight religious rituals like kissing rosary beads before stringing them around his neck or touching a portrait of a weeping Madonna and making the sign of the cross multiple times.

Serra also shows us the elaborate process of getting into traditional attire, known as traje de luces, or suit of lights, for its sequins, jewels and threads of gold and silver. I’ll confess that seeing Roca Rey squeeze himself into sheer stockings pulled all the way up to his chest, and then being assisted by a dresser to yank the decorative pants called taleguilla as high and tight as corsetry, all I could think was, “What if he gets anxious and needs to pee before entering the ring?”

It’s tough to watch a bull, riled up by banderilleros waving their cloaks, ram the armored sides of a horse carrying a lance-wielding picador, or the reddest of red blood spreading down the animal’s coat as the pronged darts are embedded like flags in its neck and shoulders. Even tougher is watching Roca Rey execute the final deadly thrust of his sword after further tiring the wounded bull with repeated runs at his cape.

But there’s a mesmerizing grace to the savage spectacle that can’t be denied, particularly in the way that the animals’ movements are echoed by those of the matador. He’s alternately balletic and feral, often snorting as much as the bull.

There’s an almost insane glint in Roca Rey’s eyes during the climactic stretch of the bullfight, and he never lessens his intensity, even in the rare moments when he turns his face to the roaring crowd in the stands to drink in the adulation. We see him being gored more than once, and in the most hair-raising instance he’s pinned against a barricade by a huge pair of horns. But the torero never loses his nerve, going back for more when others would likely be looking for medical attention.

Of course, none of this can ever justify the horror of watching an agonized bull collapse, defeated, still breathing with its tongue hanging out as a puntillero shoves a dagger through its spinal cord if it survives the sword. It’s shocking to witness the spirit of a mighty beast being systematically broken, and haunting to see the light going out in its eyes. Mercifully, we’re spared the sight of ears being cut off as trophies, though seeing the half-dead animals roped by the horns and dragged out of the bullring by a team of horses, leaving a trail of blood, is a picture not easily forgotten.

Serra lets those images speak for themselves, often accompanied by unsettling shifts in the score. There’s no commentary, no talking heads, no textual information, no reflection on his triumphs even from Roca Rey, whose face, for the most part, remains a stoic mask. Any thoughts about the violence we’re seeing are strictly our own, never fed to us by the filmmaker. That makes Afternoons of Solitude, in its uncompromising way, a doc as muscular and ferocious as the poor creatures being ritualistically slaughtered in those bullrings.