“It’s the economy, stupid,” has been the unofficial mantra of all U.S. presidents seeking reelection since the 1990s and that immortal phrase from the ragin’ cajun himself, James Carville. But Joe Biden may be the first incumbent to test that theory, as poll after poll finds that, despite the economy firing on all cylinders, Americans are steadfastly pessimistic about it.

In other words, it’s shaping up to be not the economy, stupid, in 2024. So what is it? Maybe it’s inflation after all.

Price hikes are still top of mind for voters despite peaking 18 months ago—in a March YouGov poll, Americans named it as the top issue facing the country, while inflation worries just sent business owners’ optimism to its lowest point in a decade. And while iIt’s long been known that consumers hate rising prices, but the depths of that hate—and just how differently regular voters think when compared to economists—becomes clear in a new Brookings Institution paper that aims to answer the questions posed in its title: “Why Do We Dislike Inflation?”

Its findings reveal that normal people are not like economists when it comes to this issue.

The real reaction to inflation

Ask an economist about the post-pandemic recovery, and they will cite some combination of COVID-induced shortages and supply-chain snarls, mass business closures and layoffs, hefty government spending to encourage a fast economic recovery and get more people back to work, and several years of ultra-low interest rates, although left- and right-leaning economists disagree on whether the government made the right choices.

Normal people, though, see “the economy” as a collection of different factors, only the worst of which are the government’s fault. Specifically, when it comes to inflation, people blame the government; when it comes to their wage increases, people believe they’ve been earned.

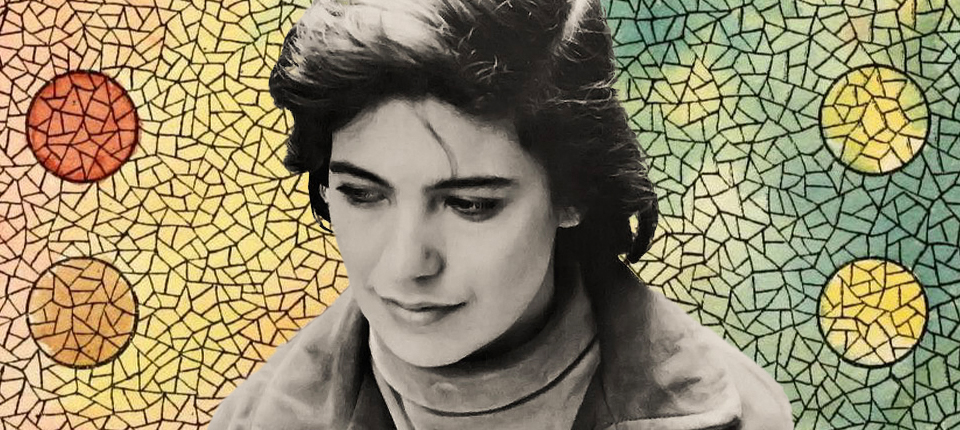

“[I]ndividuals rarely ascribe the raises they receive during inflationary periods to adjustments for inflation. Rather, they attribute these increases to job performance or career progression,” writes study author Stefanie Stantcheva, a professor of political economy at Harvard University.

Nearly half of the respondents to the survey reported getting a pay increase—but when they were asked about the reasons for the increase, people were more than twice as likely to credit their own on-the-job performance than inflation. (Among the highest-paid respondents, those making $125,000 or more, the difference was nearly three times.)

“When workers get pay increases, they think it’s their own work; when they see inflation, they think that’s bad policy,” Dean Baker, co-founder and senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, told Fortune. “As an economist, it’s annoying.”

Baker noted that this latest paper confirms and updates research dating back to the 1990s, when Robert Shiller found people angry about inflation, pessimistic about their ability to make up inflation gains with pay raises, and mistrustful of concepts that economists take for granted.

Both Baker and Shiller are worth listening to, for similar but different reasons. Baker has been blogging about economics, and media coverage of it, for decades now at Beat The Press, advocating a generally progressive viewpoint but also regularly questioning political economy, especially the employment of copyright. He was one of the few economists to spot the housing bubble before it burst in late 2007. Shiller, a Nobel laureate, also spotted the 2000s housing bubble and his name graces one of the housing market’s key indexes, the Case-Shiller.

What is inflation, anyway?

What’s more troubling is that only half of the respondents to Stantcheva’s study could correctly define inflation as a general increase in the price of goods. (A sample incorrect definition: “The hiking of prices of consumer goods to offset the country’s debt due to elites over spending and throwing money away.)

Respondents were also hazy on other economic concepts, such as the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Balancing the two is the job of the Federal Reserve, whose mandate requires it to balance “maximum employment” and “stable prices.” The Fed painstakingly tries to reconcile these two opposite forces, knowing that a tight job market can lead to slightly higher inflation (since workers have more bargaining power to demand higher pay, which can get passed on to consumers), while focusing on ultra-low inflation can keep the economy underperforming.

While most respondents in Stantcheva’s survey said there was a relationship between unemployment and inflation, only one in four correctly identified the trade-off between high inflation and low unemployment.

When respondents were asked an open-ended question about the cause of inflation, the top answer was “Biden and the administration,” followed by “greed,” “monetary policy” and “fiscal policy.” There is a partisan divide in these answers, with Democrats much more likely to answer “greed” while Republicans were prone to point to “Biden and the administration.” Respondents making under $40,000 a year were twice as likely to blame Biden as those making $125,000 and over.

Nearly no one discussed COVID-19 as a reason for inflation, although some people said “supply and demand” was a cause.

In general, inflation, or rising prices, happens when there is too much demand in relation to supply–and when that happens in several industries, like oil and gas, transportation, food, and manufacturing, higher prices can be reflected nearly across the board, according to a Harvard Business Review report. A drop in supply can also be caused by significant disruptions to resources, like labor and energy, used to fuel the economy—such as the drop in oil production and disruption in global food supplies after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, or a year before that, the shortfall in manufacturing of semiconductor chips and the hiccups in shipping that characterized global reopening. Many economists have cited these global “supply shocks” as a key reason inflation soared to 40-year highs.

Another school of thought, famously given definition by a quote from another Nobel laureate, Milton Friedman: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” In May 2023, Fortune’s Shawn Tully reported on a relation of this theory from the generally Friedmanite “money doctor” Steve Hanke, who said the “monetary bathtub” had simply grown too full during the pandemic. Inflation can also occur when worker wages are rising fast and companies pass on those wages in the form of higher prices.

When it comes to the job market, though, there are clear links to policy decisions made by Congress and the states during and after the pandemic, said Elise Gould, senior economist at the Economics Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank. After employers laid off tens of millions of workers in 2020, Congress and many states “provided more adequate unemployment benefits, and disproportionately supported those low-wage workers who lost their jobs,” she told Fortune. “They could stay afloat and were less desperate, and businesses had to work harder to attract them,” leading to today’s tight labor market. Stimulus checks to people and businesses and funding for local government also contributed, as did minimum-wage hikes in 13 states that index wages to inflation.

But among the general public, Gould said, “there’s a disconnect. I don’t think people always see how things happen in the same way [as economists].”

That’s bad news for the Biden camp, since—despite the rate of inflation falling to just one-third of its peak two years ago, Americans seem more worried about it than ever. One in four respondents to an Economist/YouGov poll in March cited “inflation/prices” as the top issue facing the nation, a higher portion than the one in five who gave the same answer 18 months ago. Perhaps reelection depends on the 10% of respondents to Stantcheva’s survey who blamed “the system.”

“No one, just the prices,” said one survey taker when asked who they were angry at. “Can’t tell if it’s the stores or the government.”