Brie Olootu pumps gas at an Exxon Mobil gas station on June 09, 2022 in Houston, Texas. Gas prices are breaching record highs as demand increases and supply fails to keep up.

Brandon Bell | Getty Images

WASHINGTON — As the White House publicly promotes falling gas prices, behind the scenes, officials worry prices could rise again as they keep looking for ways to get more oil on the market.

The White House used a drop in the average price of gas to below $4 last week to talk up President Joe Biden’s response to record-high oil prices and push back on Republicans who blamed him for the earlier price spike.

But oil traders, industry executives and former administration officials warn that prices could easily rise again as many of the issues that contributed to the spike in early summer are still a factor, like limited refinery capacity and uncertainty around Russia’s war in Ukraine. Industry experts said the White House has had a limited impact on the recent decline in prices, pointing instead to fears of a recession as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, a slight pullback in consumer demand due to earlier high prices, and an uptick in global production.

“The Federal Reserve right now is the main domestic actor on oil prices with higher interest rate hikes. The specter of recession is certainly in the oil market,” said Daniel Yergin, vice chairman at S&P Global and author of “The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations.”

Administration officials have pointed to a Treasury Department analysis showing that Biden’s decision to release 180 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserves contributed from 13 to 31 cents to the more than $1 drop in gas prices since their highs in June, with similar releases by other countries adding up to 11 cents more to the decline.

Gas prices are displayed at an Exxon gas station on July 29, 2022 in Houston, Texas.

Brandon Bell | Getty Images

But there is no indication that Biden’s other efforts, like publicly shaming oil and gas companies over their record profits, calling an emergency meeting with CEOs and threatening to pull unused drilling permits, have had any effect on price or production, according to industry experts. While oil production has increased, it has done so at a pace similar to what was expected before Russia invaded Ukraine.

“There hasn’t really been a policy that we can point you to that has helped the situation. When the executives met with the White House over the last few months, their primary message was don’t make it worse,” said Geoff Moody, vice president for government relations for the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers. “There were a lot of things that they were considering that they have not done that would have really exacerbated the situation. So to the extent that they want to take credit for anything, I would say it is by not interfering.”

Although gas prices have dropped from earlier this summer, they are still close to pre-pandemic highs. A gallon of gas is around 75 cents higher than it was at this time last year and more than a dollar above where it was in 2019 before the pandemic caused demand to tumble and oil producers and refiners to slash production.

While touting the recent decline, administration officials acknowledge that prices could rise again, though they expect prices to fall slightly more as demand typically drops in the fall. “This is a global market. Anything could happen, especially as it relates to what’s going on in Russia and Ukraine,” one administration official said.

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm pointed to a report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration that forecast prices dropping to $3.78 a gallon in the fourth quarter, saying during an interview on CNN last Sunday (Aug. 14), “We hope that that’s true, but, again, it can be impacted by what’s happening globally.”

One step the administration is looking to take to encourage oil companies to increase production is to guarantee that they will be able to sell their oil to the U.S. government at a fixed price as it begins to restock some of the barrels Biden sold off from the Strategic Petroleum Reserves.

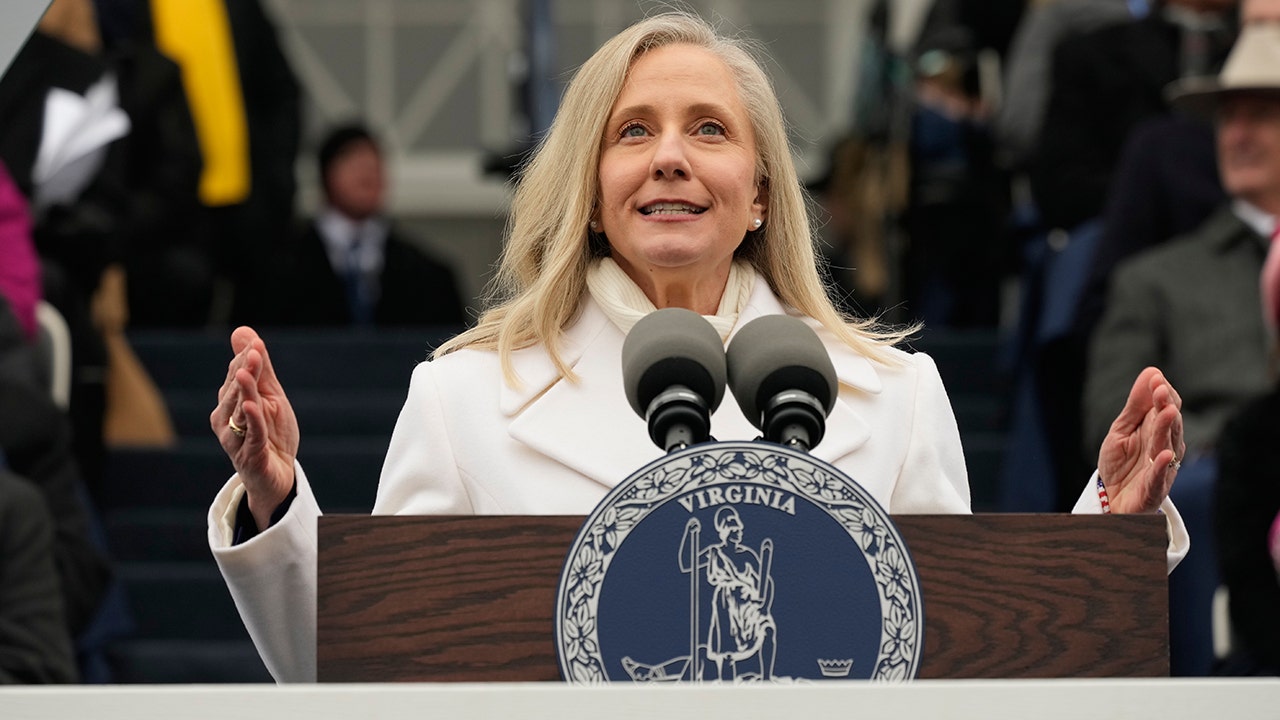

U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm speaks during a press briefing at the White House in Washington, April 8, 2021.

Kevin Lamarque | Reuters

In the past, the federal government has paid the market rate when the oil is delivered, which could be more or less than the price when the contract was signed. The official said offering a fixed price now could take away some of the risk for oil companies investing in new drilling operations that could take months or years to get up and running.

The administration has also been trying to hammer out a deal with other European and Asian allies to impose a price cap on Russian oil to bring down gas prices and cut into the Kremlin’s revenue. The countries agreed to the price cap during the G7 meeting in June with the goal of putting it in place by the end of the year. But industry analysts have warned it could backfire and drive prices higher if Russia lowers production as a result, creating an artificial shortage.

One fundamental issue is a lack of refineries to process oil into gasoline after five closed during the pandemic when demand for gas tumbled. And, next year, a Lyondell refinery in Houston producing more than 200,000 barrels per day is scheduled to close.

Another fundamental issue that remains is the tension between Biden’s climate goals centered on transitioning away from the use of fossil fuels and the need for oil companies to ramp up production to meet consumers’ continued demand.

The White House has been in regular conversations with refiners to try to identify ways to help keep production online and bring back shuttered refineries, said the administration official. In one sign of progress, PBF Energy restarted production recently on a refinery in New Jersey that would add 50,000 barrels a day in capacity, the official said.

“We are trying to unstick those issues just like we do in other areas of our supply chain, whether it comes to ports or baby formula,” the official said. “Even though these are private transactions, the government can play a role in trying to unstick any roadblocks if it’s in the public interest.”