In January 2016, I was an unpublished writer working on my first novel when I learned of an artist residency on a tiny island off the west coast of South Korea. Excited, I daydreamed of finishing my manuscript in my motherland, visiting family, and of course, eating an abundance of delicious food. As I dug deeper into the history of the island though, I unearthed troubling revelations. This artist residency had a rumored past as a concentration camp in the 1940s, under Japanese colonial rule. 선감학원 (Seongam Academy), as the camp was known, was established with the purpose of housing “vagrant” children. In reality, the children of political dissidents were abducted and forced into labor under horrific conditions of abuse. Spooked, I closed my residency application, afraid of what I’d soak in on those grounds. Coming from a family of women who have spoken to ghosts through their dreams, I know the permeability of our living world.

A few months later in April, I came across an Associated Press article that chilled me with recognition: “S. Korea covered up mass abuse, killings of ‘vagrants.’” But the article wasn’t about the Japanese in the 1940s, but rather, institutions created forty years later. I shuddered. The exposé revealed human rights atrocities at 36 “social welfare facilities” or “reformatory centers” in the years leading up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics. They found that these abuses, most notably at one of the largest facilities called 형제복지원 (the Brothers Home), were orchestrated and covered-up by the government for decades.

The 1988 Olympics occurred when I was a year old. Recent history—these institutions were in place during a time that was within reach, that could be felt in my body. Social welfare facility, reformatory institution, concentration camp: whatever the name, the facts remained the same, and it was incomprehensible to me.

I began to research these places of horror, driven by a need to understand. In the early 1980s, the South Korean government, which was a thinly veiled dictatorship, hoped to win the bid for the 1988 Olympics, seeing it as an opportunity to showcase South Korea’s rapid transformation from war-torn and impoverished into a “developed” country. The Olympics would herald international recognition and reputation. The price? Thousands of innocents, imprisoned without recourse to justice. The inmates, sometimes locked up for years, were most often from the margins of society: the houseless, the disabled, and orphaned were all forcibly removed in the government’s efforts to rectify their image. Others, too, were rounded up: street vendors, political dissidents, loitering teenagers who were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I began to research these places of horror, driven by a need to understand.

The levels of complicity were shocking. Police officers were often promoted based on the number of “vagrants” they captured, while the facility owners received government subsidies based on the number of prisoners they housed, which incentivized them to work together for mutual benefit. Once imprisoned, the inmates were forced to labor without compensation and often brutalized into submission in order to churn out financial profits. At the Brothers Home, inmates glued together shoes, sewed blankets and dress shirts, and assembled ball point pens. These products were distributed not only within the borders of Korea, but sent abroad to Japan and Europe. It’s unclear if the companies who hired these facilities knew the conditions under which their products had been made.

The parallels between the abuses at Seongam Academy, perpetuated by the Japanese, and the ones at the Brothers Home, perpetuated by Koreans in power four decades later, was uncanny, unconscionable. What did it mean that Korea’s dictators reenacted the oppression of our colonizers?

Humanity’s brutality gutted me, and I wanted to look away. I forced myself to keep researching, and soon, I became obsessed. I read as many articles I could find and pored over photographs: a truck crammed with children, a boy in a blue shirt jumping off the back, unaware of what lies ahead. A crowded room of girls in beige sweats, bent over sewing machines. Boys in striped tracksuits gluing soles onto leather sandals in a dark room.

Strikingly enough, the reenactment of the country’s oppression happened on a microcosmic level as well. Within the institution, inmates were encouraged to betray one another for personal benefit. Those who exhibited allegiance to the leaders rose through the ranks, becoming guards with access to tools of violence, which were then used to control their peers. The limits of our humanity fascinated me—how could a person who had endured such abuse then justify their behavior and complicity as abuser?

How could a person who had endured such abuse then justify their behavior and complicity as abuser?

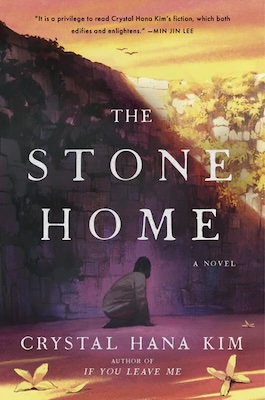

A year later, I began writing what would become The Stone Home. I wrote not to find clean answers, but to wrestle with the unknowability of ourselves. I wanted to understand our darkest impulses. If I were imprisoned, how would I behave? What lengths would I go to protect myself, or someone I loved? Under what circumstance, if any, would I betray my peers?

As I tried different narrators and approaches into the story, I found myself stuck. I set aside my scattered pages, unsure of how to continue. I had gathered information, but I couldn’t imagine myself into the body of my characters. I needed to learn more.

On a rainy afternoon on April 23, 2018, two years after I had first read about the Brothers Home, I arrived at the Seoul National Assembly. On the sidewalk outside the government building’s gates, I found a makeshift hut next to a wall of posterboards. The images: a room full of boys kneeling beside bunk beds, children shoveling dirt and hauling wood, and infuriatingly, images of the director of the Brothers Home receiving an award for his efforts at social reform. There, a man greeted me in a bright yellow zip-up jacket. He had dark hair streaked with gray and wore glasses spotted with rain: Han Jong-Sun, a survivor, an activist, and the man I had been looking for.

Accompanied by my aunt, who acted as my cultural and linguistic interpreter, we went to a nearby tea shop, and then later, to a restaurant. Over many hours, Mr. Han described his life before captivity, how he was caught when he was 9 years old, the grueling days within the Home, the violence which he both endured and witnessed. He detailed the hopelessness he felt, the competitive tensions amongst the prisoners, and the community he forged with a few friends. The despair that consumed him as an adult, physically released if still not mentally uncaged. It was only when he began advocating, despite fear of retribution from those in power, that he found purpose. Since 2012, Mr. Han had been protesting, demanding apology from the government for their crimes.

While Mr. Han spoke candidly, I also felt his guardedness: What would I do with this information he shared? Why, when so many people were unwilling to look, did I want to write about this ugly period of our history? As somebody who had survived the horrors of one of these institutions, trust had to be gained.

He detailed the hopelessness he felt, the competitive tensions amongst the prisoners, and the community he forged with a few friends.

We spoke for hours. He asked me to consider: what if I had been a kid walking along a beach on holiday and I was taken by cops, simply because I didn’t have my identification papers? This happened time and again, so much so that my aunt exclaimed in sudden recognition. In her youth, there was a saying adults used to scare children into obedience: If you’re out late at night, the men will get you. She had always thought it was a figurative spook, a made-up story.

Though I wanted to write about our Korean history, I knew that similar institutions had targeted Indigenous Australians, First Nations children in Canada, and Black Americans. Migrant children are being imprisoned at the border of the United States right now, as I type these words. I spoke to Mr. Han about how this repetition and refraction of history is what propelled me to write. There were questions I wanted to untangle: What does it mean that state-sanctioned violence happens across cultures? Whose stories are silenced, and how does that erasure contribute to future crimes against humanity? How do we create change?

At the end of our conversation, Han Jong Sun wished me luck and asked that I treat this subject matter with care and respect. He asked me to not only witness, but to act.

Mr. Han’s directive fueled me. I crafted an institution that was modeled on what I’d learned of Seongam Academy and the Brothers Home, buttressed with layers of fictionalization. I wanted to represent the abuses that occurred, but I didn’t want to speak for the survivors. Fiction has the ability to carry you into the body of another, to allow you to feel and taste and move and experience. Fiction can ask you to witness by subsuming you into the life of another. This was my hope for my novel, and the force behind my characters. We have fierce, protective Eunju as our narrator, and she works hard to protect her resourceful, underestimated mother Kyungoh. Stubborn Sangchul is our second narrator, imprisoned alongside his idealistic older brother Youngchul. Grief-struck Narae opens the book in 2011, and insists on excavating the truth to the very end.

I wanted to represent the abuses that occurred, but I didn’t want to speak for the survivors.

As I wrote, I realized that I had been fixated on the injustices of these institutions, but equally important, as Mr. Han had taught me, was survival through community. Looking back at my research, I lingered on a story of a group of girls who escaped the Brothers Home by working together in secret. I incorporated this coming-together, this solidarity among the imprisoned. Without each other, we cannot survive. Without each other, we cannot create a more hopeful future.

My wish for the readers of The Stone Home is that they can feel this thread of optimism and connection. I want it to buoy them, as it did me. I also hope, reader, that you don’t look away from the hard parts. It is only by knowing our past that we can guard against the future.