The Oscars are Sunday! For those of you haven’t managed to watch all of this year’s nominees (or even if you have and would like a refresher), we’ve put together a handy cheat sheet to help you stay super informed for the ceremony’s likely shots, underdogs, and inevitable twists and turns.

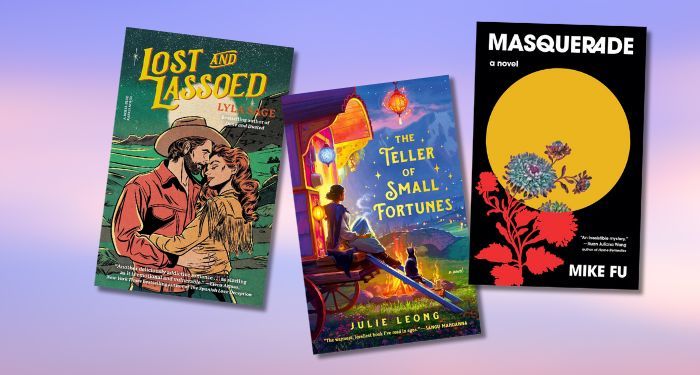

First, Ryan Coleman broke down all the literary adaptations nominated this year.

Next, here are our picks for last year’s best literary adaptations.

Now, on to the contenders:

Oppenheimer

Read Claire Tuna on STEM on film and Oppenheimer as a craft movie:

“Oppenheimer chafes when it uses scientific settings only as texture, when its digressions lean irrelevant, hagiographic, and intentionally showy. But when Oppenheimer lets us in on the work itself, when it lets us assess the goals, risks, and costs of the Manhattan Project, and with that knowledge, reach our own conclusions about the person in charge (that is, if are able to tune out the voices calling him things like “actually important” or “a prophet”)—that’s when the movie finds its groove.”

Read the rest here.

Read Alok A. Khorana on Oppenheimer and the Bhagavad Gita:

“Robert Oppenheimer was born to Jewish parents affiliated with the Ethical Culture movement, in which he would receive his schooling. At Harvard, he was drawn to the Hindu philosophical classics—seemingly more interested in these than even physics. In his thirties, on the faculty at Berkeley, his curiosity deepened. He studied Sanskrit weekly with a Sanskrit professor. It was here that he was first introduced to the Gita, which he thought “quite marvelous”; later he would call it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.”

Read the rest here.

Read Lauren Carroll Harris on two forgotten Oppenheimer films:

“The Day After Trinity (1981) and The Strangest Dream (2008) evacuate the mythical tropes of the tortured genius biopic that Hollywood loves to rehearse in films like The Imitation Game, Hawking, and A Beautiful Mind. Now enjoying a renaissance, the films are neither unforgiving nor hardline, but offer sharper moral clarity to the Oppenheimer dilemma, presenting a more complex (and condemning) portrait of the father of the atomic bomb: a patriot, philosopher-king, skilled public administrator, scientific collaborator with military and government, emotional naif, egotist, and polyglot.”

Read the rest here.

The Holdovers

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“It is a pentathlon of a film, a mesmerizing, near nonstop parade of achievements; not in a long time have I watched a film that succeeds so well in combining hysteria with pathos, nostalgia with cynicism, solemnity with irreverence. It’s the best holiday movie since Elf, that’s for sure. Hemingson‘s script manages to feel incredibly real while following a perfectly sculpted narrative arc; every quip, every line is its own quiet little masterpiece.”

Read the rest here.

Rutigliano also writes about how nobody’s doing it like Paul Giamatti.

“But if I am to invoke the Muse (in Homeric terms) at the start of this article, I would borrow the words of Robert Fitzgerald, who appealed, in 1961, “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of that man skilled in all ways of contending, the wanderer, harried for years on end.” I’m drawn to this version, in which the speaker asks the Muse to animate his own telling of the tale rather than impart it to him, and I find it a fitting entreaty for the purposes of this article, which is to give an account of a wonderful story I already know: that of the venerable and varied career of Paul Giamatti, the battered, wayfaring, under-sung hero of modern cinema, an actor who takes the portrayal of the everyman to extraordinary and in fact epic heights.”

Read the rest here.

Maestro

Read our review, from Frank Falisi:

“The film is maybe not about Leonard Bernstein at all, or it can be not about Leonard Bernstein. What if the biopic wasn’t a lesson in a life lived but a version of something, an acting out of feeling? Past all the conditions that familial estates, cultural institutions, or communal memories impose on individuals to render them idol or idle, Maestro is inoculated from the prison of good taste by having none. This is its real contradiction: it is both the question of a Bernstein biopic and the answer of having nothing (everything) to do with his life.”

Read the rest here.

Read Ben Rybeck on Bradley Cooper’s A Star is Born:

“See, there’s something rotten in this entire frame that even infects a good movie. Because Cooper’s A Star Is Born is good in all the ways that most good movies are good, which is to say, the acting is good, the dialogue is good, the cinematography is good. Good, compared to the other ones, which are bad. I mean, very bad. I’m on safe critical ground here, I think, except for the 1954 one, which lots of people consider a beloved classic but which I found interminable. Nevertheless, nobody seems to really watch the 1937 one anymore (except for articles like this), and the 1976 one has zero defenders I can find. That one, in particular, is plainly bad. Again, there’s a moment where she doesn’t know what a pepperoni pizza looks like!“

Read the rest here.

Past Lives

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“Truthfully, I’ve been struggling to write a review of Past Lives since I saw a preview a few weeks ago. It broached a very tender part of my soul and I’ve been having trouble going back there simply to write 1,500 words. Let this be an endorsement that Past Lives, which was written and directed by Celine Song, is an excellent film, a beautiful and moving film, a film which captures so perfectly the secret uncertainty of choosing a path and allowing it to define your life.”

Read the rest here.

Read Alyssa Songsiridej on Past Lives and its lack of regret:

“But the film does something much subtler and smarter than simply reiterating received ideas about the internal lives of immigrant women. The opening shot, in fact, seems to deliberately toy with the audience’s expectations: the three leads are shown at a distance in a New York City bar, while two people speculate via voiceover about their relationship to one other. Are the Asian people together, or the Asian woman and the white guy? What narrative can we, the viewers, shove these characters into, guided inevitably by the question of which love interest suits Nora best?”

Read the rest here.

Killers of the Flower Moon

Read Claire Tuna’s review from Cannes:

“A slow exploration of greed, power, corruption, and betrayal sets a tragic love story between DiCaprio’s ex-infantry Ernest Burkhart and Lily Gladstone’s wealthy Native American Mollie Kyle against a series of murders at the hands of Ernest’s powerful uncle William “Bill” Hale (Robert De Niro). In true Scorsese fashion, the legendary filmmaker manages to sneak in elements and themes that appear throughout his past work, especially his gangster films, yet his approach to storytelling still feels refreshing.”

Read the rest here.

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“Scorsese’s film, which is 3 hours and 26 minutes, is a gut-wrenching story told with ample thought and care—it is clearly invested in doing right by the Osage people of then and now. The Osage’s participation in the making of the film has been well-publicized, but it’s clear, when viewing the film, that Scorsese not only wants to get the historical details right without exploiting the Osage or their suffering but that he also wants to tell the story in the most respectful, collaborative way possible. In one scene in particular, Scorsese acknowledges a kind of lurid true-crime reportage that (he wants to make clear) this film is not. At the same time, in order to be its most respectful and compassionate version, the film might have focused less on Ernest. Scorsese likes an antihero, and a man who experiences such absurd self-denial that he can’t fully understand the impact of his being a serial killer annihilating his wife’s family for personal gain, is certainly that kind of protagonist. Scorsese is perhaps too curious about fleshing out Ernest’s feelings and conflicts instead of accepting that he is a walking contradiction, made into such by white supremacy.”

Read the rest here.

Poor Things

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“Poor Things‘ question of “nature vs. nurture” underscores the work of Victorian scientist Francis Galton, which keeps it in line with its Victorian setting. But Poor Things doesn’t have a historical setting like The Favourite does; the late Victorian world of Poor Things is a dream, a pastel, futuristic wonderland full of kooky and supercilious technologies and an architectural style that only can be described as “Antoni Gaudí on acid.” (At times, it’s “Gaudí on DALL-E.”) Except of course for the black-and-white sequences in Godwin’s laboratory-cum-home, which are heavily indebted to James Whale’s films Frankenstein (1931) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).“

Read the rest here.

Read Jonathan Russell Clark on Alasdair Gray and the novel Poor Things:

“My only concern, though, is that any cinematic version of Gray’s inimitable tales necessarily omits some of Gray’s most innovative techniques, which do more than simply adorn his narratives with postmodern festoons, but add realist weight to his sometimes bizarre stories and also provide comparative context to our own world, so that we can see how the absurd, grotesque, and downright filthy stuff that happens in Gray’s diegeses relate—are, in fact, meant to directly compare—to our own reality.”

Read the rest here.

Read Mazin Saleem on Alasdair Gray’s other novels:

“But it’s in the Babelesque story “The Axletree,” told in two halves bookending this five-story sequence, that Gray is at his epic best. Another Emperor features, this one hoping to solve the problem of imperial collapse by constructing a never-ending tower, the top of which, unfortunately, touches the heavens. With its Hebrew cosmology and deluging finale, the story shares much with Ted Chiang’s award-winning “The Tower of Babylon” from a decade later. But that simpler and smaller-scale story—notwithstanding its massive tower—doesn’t have half the poetry of Gray’s, with its finger-melting sky in “slender rippling rainbow” colors. Neither does it have the same scope; via the story of the tower, Gray condensed Western history in the time-trotting style of Jacob Bronowski or E H Gombrich. Yet he made sure the story was overdetermined enough not to be an easily dispatchable allegory. And just when the hand of its politics gets heavy, the story ends with one of the most awe-ful revelations in literature.”

Read the rest here.

Anatomy of a Fall

Read our review, from Julia Sirmons:

“Anatomy of a Fall, the new film by Justine Triet, is a riveting drama about the writer-as-suspect. It begins as a fairly straightforward murder mystery. Samuel, a writer and teacher, is found dead after falling from the attic of his house. At first, the fall seems to have been an accident, but the authorities find some suspicious blood spatter evidence that calls this into question. His wife Sandra, the only other person in the house at that time, is charged with his murder. Evidence comes out that suggests their marriage was not as happy as it seemed. Sandra’s skill and identity as a writer becomes a key issue in her trial, where the style of the fiction writer meets the language of the law.”

Read the rest at CrimeReads.

Barbie

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“Barbie combines the rules of the movie musical’s imaginary netherworld with the investments of a Beckett or a Ionesco play. We’ve all seen plays where human actors play unwieldy concepts like “the city of St. Louis” or “polio” or even real material things like “bullets.” That’s the variety of inquiry Barbie is; yes, it explores the complex figure of the Barbie Doll through cinematic conventions of faux-documentary, movie-musical, and traditional Hero’s Journey narrative, but it also is simply an unreal experiment, a highly symbolic exercise where theoretical entities get to speak for themselves, and where real people get to tell anthropomorphized theoretical entities what effects they have on the human experience. The whole movie is a mise-en-abyme-heavy dream sequence, a fantasy of a dialogue between real women and womankind’s evolving, go-getting golem plaything.”

Read the rest here.

Read Orlando Reade on Barbie and Paradise Lost:

“Like Milton’s Eden, Barbieland also contains the seeds of its own destruction: gender inequality. Ken exists in a state of perpetual anxiety, hoping only to please Barbie. In this, he resembles Milton’s Adam. When Eve is born, she falls in love with her own reflection in a pool of water. On first seeing Adam, she is unimpressed. Adam worries about her self-sufficiency and complains about his desire for her. Milton is said to have invented the word “self-esteem,” and that is exactly what Adam lacks. Fear of living without Eve compels him to eat the fruit. Both Ken and Adam suffer from patriarchal rage. When Barbie and Ken travel to the real world, the sight of Los Angeles leads Ken to recognize his own frustrations. He returns to Barbieland to establish the patriarchy there, and it falls to the Barbies to restore order.”

Read the rest here.

The Zone of Interest

Read Claire Tuna’s review from Cannes:

“Glazer succeeds at making a Holocaust film that is completely unlike any we have seen before. The violence and brutality occuring within the camps that are often depicted on screen isn’t portrayed in the film, which uses the Höss family’s indifference to what happens beyond the walls of their idyllic home as a way to communicate the full scope of their evilness. We see them throw parties, have picnics, and spend time tending to their sprawling garden, while the outside horrors continue to loom.”

Read the rest here.

American Fiction

Read our review, from Olivia Rutigliano:

“American Fiction represents existence as a cyclical process of alienation from and then rediscovery of the self; Monk is experiencing the former part while nearly everyone around him is experiencing the latter. There’s another part, too, which involves discovering how others see you and want you to be.”

Read the rest here.