This was a regular feature of my childhood, though it feels so long ago and far away, conceptually as well as literally, that I nearly forgot it ever happened: I’d go into town to the mall with my mom, and she’d drop me at the doors of the Borders or Barnes and Noble while she ran errands. I’d go inside and browse the shelves, and collect a pile of ten or so books that I thought looked interesting. Then I’d carry my stack around the aisles until I found an open armchair.

I’m sure some of the enormousness of the overstuffed Swiss-dotted armchairs is attributable to the fact that I was a child, but in my memory they were huge, with armrests to rival the size of the seat. The chairs were flanked by two side tables, usually already piled with books from previous sitters. I’d put my stack of books down, cozy up in the big armchair, and start reading.

I’d read ten or twenty pages or so of each book, depending on how much they grabbed me. If it wasn’t hitting, it went into the reject pile. If I liked it, especially if I could barely bring myself to stop in order to peruse the next book, I’d put it in a separate pile, the “beg mom to buy” pile. I always tried to winnow this to two or three books, so as not to press my luck. But all told, this would occupy me for a couple of hours. I spent a lot of time as a kid this way, and it was formative. Reading made me a reader, but so did having a place that allowed that experience to be pure, self-directed, and self-contained.

In the last several years, I’ve struggled with being “a reader.” Part of the problem is that I work online, and the onslaught of content to read online is constant. But if I look around, certain things that helped make reading to be a core part of my life have disappeared. One of them was being able to peruse the merchandise of a bookstore, comfortably, at my own pace.

In the time since the bookstores, I’ve worked retail at Best Buy and The Gap, and as a cashier at a local grocery chain (hey-o, Price Chopper). Over that time, I saw the rise of the concept of “customer contact.”

Shoppers may not know it, but essentially all corporate retail employees—in clothing stores, shoe stores, candle stores, makeup stores, everywhere—are coached to let no more than a very small amount of time go by between when a customer enters a store and when they are “contacted”—greeted, asked if they’re looking for anything in particular, invited to let the employees know if they need any help.

This is not really a customer service thing; it’s what the biz calls a “loss-prevention” (read: theft-prevention) thing. Customer contact tells the customer, very subtly, that they are seen, they are being watched. A customer who feels un-perceived will be more likely to steal than one who doesn’t. (This is why self-checkout engenders so much theft.) But businesses have adopted this customer contact practice as if there was nothing to lose on the other side of the equation.

Even as someone who has done countless “customer contacts” in my retail career, knowing everything there is to know about them, I still find them incredibly annoying. Contrary to the surface philosophy of customer contact, I don’t actually need an outright invitation to feel like I’m allowed to ask a paid employee of the store a question. As much as customer contacts may do for loss prevention, they also represent a loss of autonomy and trust, a lack of faith that I, the customer, may behave myself, that I may even (gasp!) make a purchase without a store employee looming over my shoulder.

By contrast, I can’t remember a single time a store employee ever bothered me while I was sitting in one of the grandma chairs at a bookstore. I wouldn’t be surprised to hear from a former bookstore employee that, at that time, in that situation, the philosophy of customer contact was the opposite: leave the customer the hell alone; they are busy, they are doing exactly what we want, they are finding something to buy. Why would we interrupt that? I was treated more like an adult, as a kid in retail stores, than I’ve ever been treated as an adult, while an adult, in a retail store.

I still like to go to bookstores because they were among my purest and best childhood experiences. But I can’t replicate the experience at all, because now, there is nowhere to fucking sit down. Not even so much as a two-legged stool. You want me to stand here as my legs fall asleep while I try to get far enough into this Kim Stanley Robinson book to see if it’s gonna connect? I’m supposed to just juggle ten potential books in my hands?

The closest I get to the chair experience now is downloading Kindle samples, which are free and let me get an idea if I’ll like the book or not. But there’s no sanctity to this activity; it’s just me squeezing in a few pages between articles and group chats and my own work. Worse, it’s virtually impossible to browse books online. How many reviews a book has or how highly a bunch of strangers rate is little more than random noise.

Virtually every book that has changed how I think has a 3.5 on Goodreads; I’ve hated most books that were a 4.5 or higher. Bestseller lists are useless, and can’t be scanned as quickly or effectively as you can scan a bookshelf. A bookstore quickly tells you a book is popular by putting it on a particular table, or facing it out on the shelf. I always skipped those tables back then, because I probably already knew about all those books; online, they are basically all you can see.

When I think fondly of bookstores, I’m not thinking of how smooth the cashier transaction was, how large or well-organized the shelves were, how many employees asked if they could help me find anything. I’m thinking of getting uninterrupted time to read.

The main thing that has come of buying books online, for me, is buying books I’ve only heard about, books it “sounds like” I will like. My bias is that I can’t read something that sucks, and nothing I can learn about a book’s metrics can tell me if I think it will suck–not topic keywords, plot, characters, fiction, nonfiction, setting. Most of the “readers also like” recommendations positioned next to books turn out to be like someone recommending that I go to Olive Garden because I said I loved going to Italy. The internet has tried, and it only fails. Not only is the entire recommendation and ratings system useless, it just underlines the fact that the only thing that really works for finding books I will actually read, is the bookstore chair.

As someone who’s been desperate to regain their reading momentum since 2017, the number one killer of “reading books ever” is “trying to read a book I don’t click with at all,” which has extremely high overlap with “books I buy sight unseen, online,” thus saddling me with the obligation to actually read it. What is it to “click” with a book?

I can’t really tell you, except to say with absolute certainty that it will happen, or not, if I can just get a chance to read a little of the book, before buying it. In fact, the only way I can keep any reading momentum at all is having carte blanche to read the first ten or twenty pages of a book, find out I hate it, throw it over my shoulder, and never think about it again. I’d forgotten this completely in the time that it took bookstore chairs to vanish.

It is obvious why bookstores eliminated chairs: They are far from efficient. A person who is sitting is yet another person who must be monitored, who isn’t actively buying anything. Chairs are a place for interlopers to park (specifically unhoused people, I’m sure, were particularly distasteful to the business consultants who evaluated the chairs and found them wanting). This isn’t your mom’s living room, I could see some MBA grad saying. But it mattered to me to even just go into a store and see other people in the chairs, absorbed in some book, working their way through their own stack. We were a cohort, however silent. It was a special thing to find an open chair.

The chairs probably got dirty and damaged easily, and needed replacing more often than most things in the store. Just one person pisses in it—some dude who had one too many at the Hooters downstairs; a baby—and that’s probably the end of that chair. The chairs encouraged people to take books off the shelves and leave them sitting on the table, where they then had to be reshelved, which I imagine is costly in terms of labor. I’m sure they were among the first things to disappear when costs needed cutting. Metrically speaking, the bookstore armchair only offends.

The specific failure of the data-driven times we live in is that it’s impossible to turn “how many books those chairs sold me on” into a P&L line item. Without those chairs, as a kid, I wouldn’t have been in that store. I’d have been roaming the halls, in the food court, maybe in the arcade where, for the price of a few tokens, I could at least sit down in the Jurassic Park game cabinet. Without those chairs, I might have decided books were less interesting than everything else a mall had to offer, and grown up to be a non-reader.

More to the point, it’s impossible to turn the good feelings I got from those chairs into a quantifiable profit. My home life with three siblings and constantly irritated parents was chaotic, and I had no space to myself, mentally or physically. In the bookstore I could just read, the one thing a reader of books wants to do, and no one would bother me.

In a time when retail stores are desperate for foot traffic and real live customers, this feels like such an easy W that I’m mystified no one’s doing it. How is it that public libraries, with barely the shavings of a municipal budget, manage to have seating, while I can’t get so much as a three-legged stool at the new neighborhood bookstore that stocks entirely based on what’s currently going viral on TikTok?

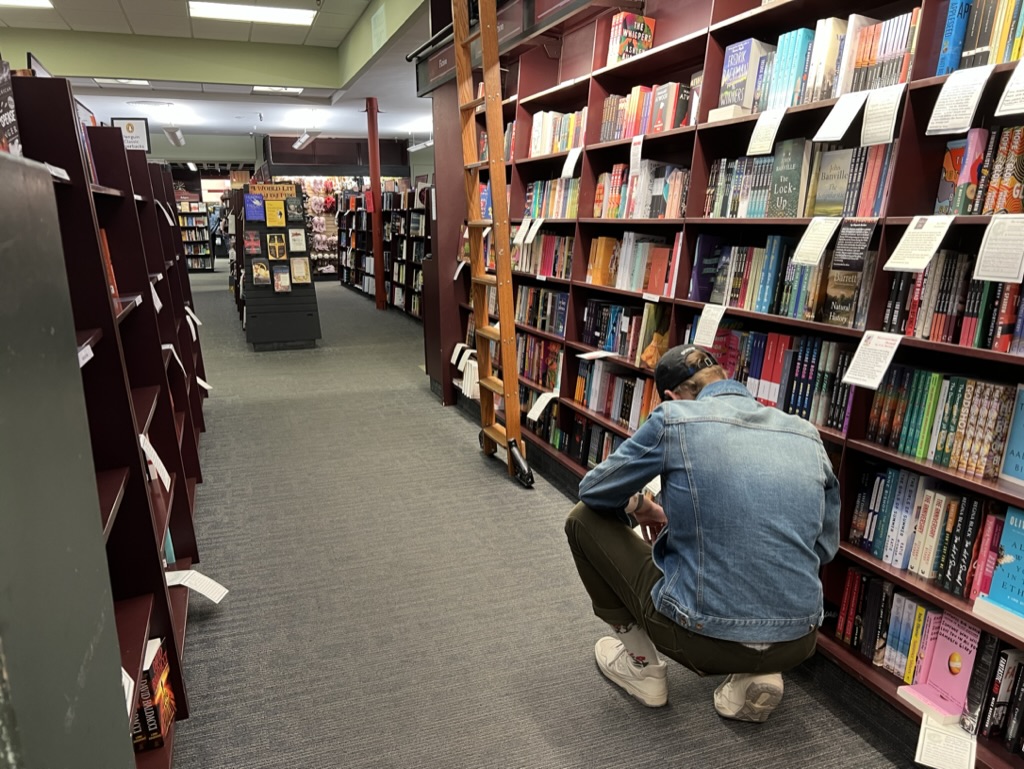

Do you know what people do now, in bookstores, when they want a moment of peace alone with a book? They crouch on the floor. Yes; they huddle like a small animal against a storm, pressing themselves up against the shelves, hoping not to get tripped over, while they try to see if a book is any good or not.

When I think fondly of bookstores, I’m not thinking of how smooth the cashier transaction was, how large or well-organized the shelves were, how many employees asked if they could help me find anything. I’m thinking of getting uninterrupted time to read. I’m thinking of finding a good book to buy, not as determined by its cover or author or marketing language on the back, not because it was on a particular table, not even because a store employee found it and sang its praises, but because I got to sit down and read it myself for a while, and come to my own conclusion on my own time.

I know I sound like Greg Kinnear in You’ve Got Mail lamenting the loss of the typewriter. But I don’t really want to reverse any tides. I just want to sit down and read where no one will bother me, and be alone with some books I haven’t decided to buy yet.