Over the holidays, while traveling out of state to visit family, I left my outsize houseplant collection in the hands of our pet sitter, a wildly talented cat whisperer but a less-than-expert caretaker of calathea. I feared the worst: that I would return to a home full of ex-flora, the floor covered in brown leaves, the terracotta pots empty and gaping where green life once flourished.

My fear led to more than a couple bona fide nightmares that week, but much to my relief, my babes all semi-survived, and I am slowly nursing them back to their former glory.

This deep love I feel for plants—and indeed for all kinds of more-than-human life—may seem strange to some. After all, a pothos can’t hug you back.

But such love is an increasingly common thread in contemporary nature writing. While one might argue (persuasively!) that love is what inspired the very first nature writers, the genre has engendered an increasingly complex way of thinking (and feeling) about nature in recent years.

For many, “love” for the natural world is no longer defined solely by one’s appreciation for it, but rather, by how one’s self and community has been defined and shaped by it, by a desire to protect and grieve for it, by an understanding that humans actually aren’t separate from nature at all—but in kinship with it.

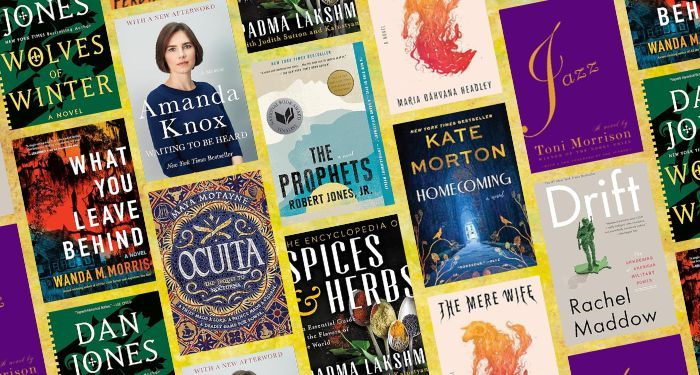

To read a number of nature-themed books forthcoming in the first half of 2024 is to be reminded of just how far and deep this love goes for many. Here is a list of some of my favorite titles out this year.

*

Erika Howsare, The Age of Deer: Trouble and Kinship with Our Wild Neighbors

(Catapult, January 2)

Deer, writes Erika Howsare, “occupy a middle zone between…domestication and wildness.” Unlike dogs, the colloquial best friends of man, they’re far from tame, but yet they live among people in suburbs and rural areas alike. They certainly live near Howsare, who opens her meditation on the connection between humans and deer with a story about observing a doe nursing her fawns.

From there she asks hard questions about how human development and ways of thinking about nature often determine whether deer live or die, and how they do both. Here, deer come to symbolize “the way we live with nature now” and perhaps how we will live with it in the future. But more than symbol, the deer is also depicted as our neighbor, our kin, the object of “a sacred bond.”

Miriam Darlington, Otter Country: An Unexpected Adventure in the Natural World

(Tin House, February 20)

In this charming book, Miriam Darlinton spends a year exploring the world of otters, speaking with scientists, writers, conservationists, and others—people who truly love these aquatic mammals. She learns about new scientific discoveries as well as the animals’ cultural importance, tracing myriad ways in which otter life is tightly connected to the world of humans.

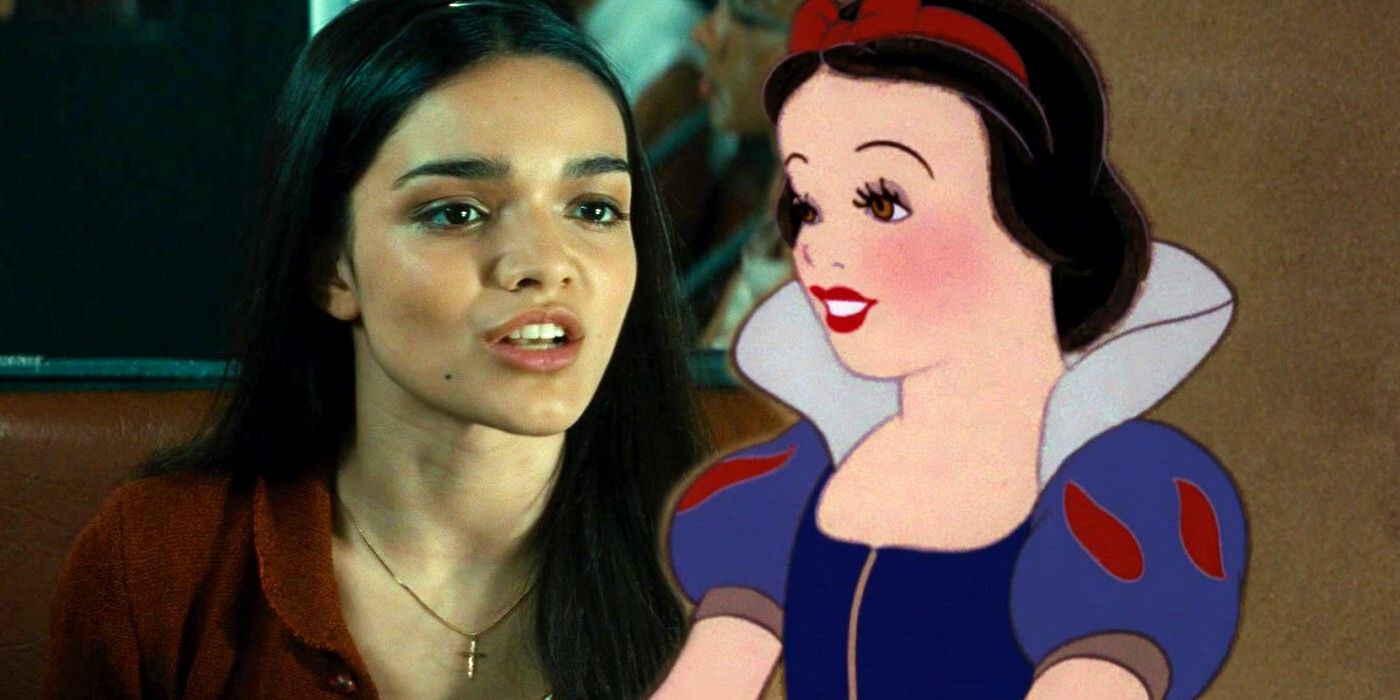

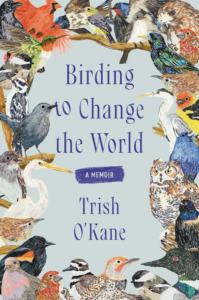

Trish O’Kane, Birding to Change the World

(Ecco, February 27)

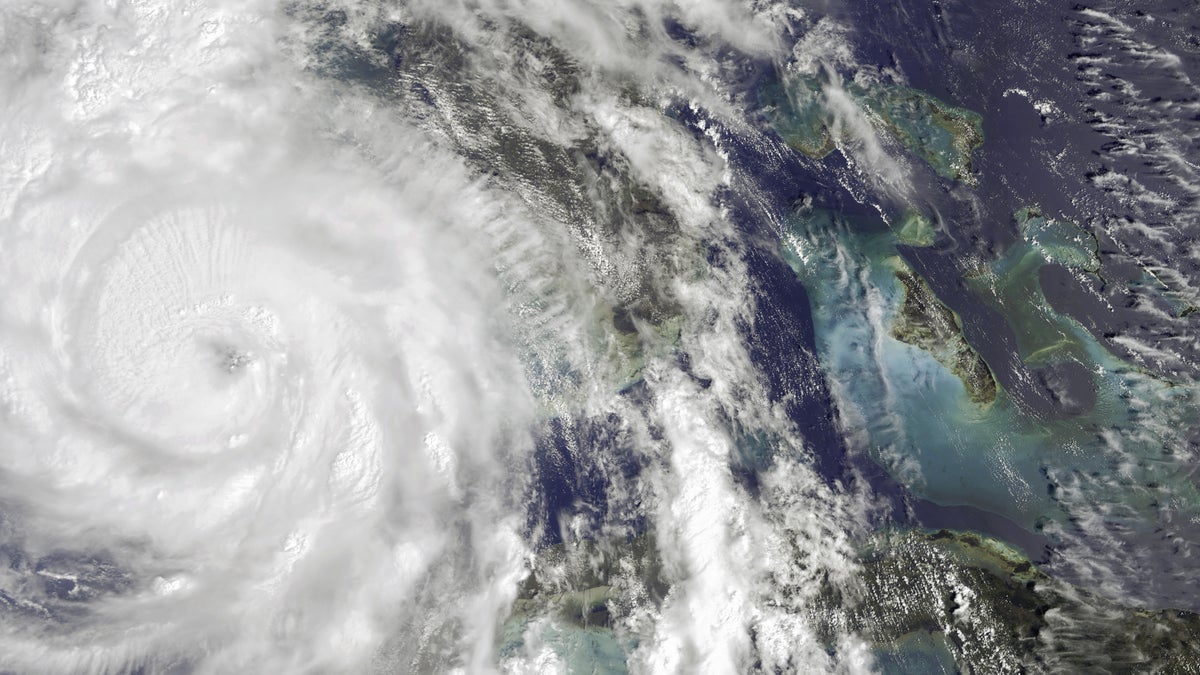

An investigative journalist, Trish O’Kane never thought much about the natural world. But then Hurricane Katrina destroyed her home in New Orleans, and she was left wondering how to move forward. The path she found was chirping and fluttering with birds. The city’s feathered residents cheered her spirit and gave her hope for the future.

After a move to the Midwest, she finds a flock of likeminded neighbors who come together to save a local park, a green space where human and avian parents both watch and raise their young. This is a love letter to birds—and to the people who love them.

Jessica J. Lee, Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging

(Catapult, March 12)

In fourteen essays filled with personal stories and social history, the award-winning memoirist and nature writer explores what it means to perceive of some plants as “out of place” in a world where imperialism and international travel have brought countless seeds (and people) to new homes, thousands of miles from where they originated. Lee evokes a centuries-long history of border crossings—by people and by plants—to throw into question what it means to really belong, love, and protect, and what our collective future might hold on a planet forever evolving in the wake of trans-continental migration.

Daniel Lewis, Twelve Trees: The Deep Roots of Our Future

(Avid Reader Press, March 12)

Recent studies reveal that groups of trees live almost like families, protecting and caring for each other. There is much to ponder about their existence beyond their stately presence. In Twelve Trees, Daniel Lewis travels the world to meet a dozen unique specimens with the aim to learn more about how trees live and communicate—and what their connected lives might tell us about how we live ours.

Brimming with awe for the overstory, the book is also a reminder that life unlike our own is not only mysterious—it’s precious.

Lydia Millet, We Loved It All: A Memory of Life

(W.W. Norton, April 2)

In this memoir-esque ode to the more-than-human world, the author asks hard questions about the present and the future: What does humanity owe other species, when our existence threatens theirs? What might our relationship to plants and animals look like if we were to better understand—and respect—their cognitive abilities, especially those so unlike our own?

“Our old home is gone,” Millet writes, in a lament about how the climate crisis has altered the planet. So, how do we celebrate and love what is left? In turns heartbreaking and inspiring, We Loved It All reminds us to hold every being dear at a time when we all need love more than ever.

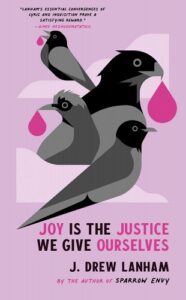

J Drew Lanham, Joy is the Justice We Give Ourselves

(Hub City Press, April 2)

This book stands out on the list because it contains poetry—a kind of environmental writing sometimes overlooked by fans of the genre. The poems (and the prose) collected here are rooted in lived experience and keen observation of the natural world. Throughout, the award-winning Sparrow Envy author and certified wildlife biologist finds profound connections between that which threatens wildlife and centuries-long systemic racism, charting a map from our brutal past, to our meta-crisis present, toward a hopeful and more equitable future for all living beings. It’s a deeply personal book that evokes joy and reflection by a writer whose generosity of spirit emanates from the page.

Zoë Schlanger, The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth

(Harper, May 7)

Poets have long understood the intelligence of plants, and now scientists are catching up. In this fascinating journey through contemporary botanical research, Zoë Schlanger explores how new studies are exploding old scientific understandings surrounding what plants are capable of and how they experience the world.

Here, plants are revealed to be beings of great talent and creativity, with the abilities to store memories and trick animals and humans who venture too close for their liking. They are, in other words, complex beings who need us far less than we need them.

Craig Foster, Amphibious Soul: Finding the Wild in a Tame World

(HarperOne, May 14)

In this touching memoir, Craig Foster leaves his exhausting life in the city for the slower pace of his place of birth, the Cape of Good Hope, where he takes daily dives into the sea. The ritual renews his sense of self and deepens his feelings of connection to the plants and animals around him. As the book unfolds, we watch his admiration grow into a way of living and thinking that’s more aligned with the natural world.

Amy Stewart, The Tree Collectors: Tales of Arboreal Obsession

(Random House, June 11)

In turns funny and poignant, The Tree Collectors is an empathetic look at the world of people who spend their lives in pursuit of priceless trees. Amy Stewart’s characteristic wit is on full display as she speaks with tree collectors from around the world. Such conversations reveal more than the ins and outs of an uncommon hobby, however; they show that the desire to collect trees stems from a desire to connect with others and envision a future in which trees and humans alike can thrive on a healed planet.

Adding to the book’s charm are Stewart’s own watercolors of the people she meets along the way.

Olivia Laing, The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise

(W.W. Norton, June 25)

At the dawn of the pandemic, with so many outdoor public spaces closed, The Lonely City author dreamed of wild escape and began to restore an eighteenth-century garden in Suffolk. Surrounded by centuries-old walls and overgrown with rare plants, the ancient garden became a private Eden—a privilege not lost on the author. Indeed, the garden inspired deep study into the history of land ownership and domesticating plants, an exploration of the “cost of building paradise.”

We see Laing’s research entwined with vignettes of her own restoration work, during which she ponders how to build “versions of Eden that weren’t founded on exclusion and exploitation.” Instead, she seeks ways of caring for the natural world that offers refuge to plants, animals, and humans alike.