There’s joy and melancholy and a lyrical connection to nature in The Eight Mountains, Felix van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch’s reverential adaptation of the best-selling 2016 novel by Paolo Cognetti, winner of Italy’s prestigious Premio Strega. What’s missing is conflict, plus a narrative drive that fully liberates the story from the page. While Luca Marinelli and Alessandro Borghi bring depth to protagonists who met as boys in a tiny mountain village that has a lifelong hold on them, the filmmakers’ over-reliance on binding voiceover passages is just one way in which the drama remains frustratingly literary.

Belgian writer-director van Groeningen, best known for his 2012 bluegrass-infused drama of love and sorrow, The Broken Circle Breakdown, here shares the reins with his actress partner, Vandermeersch. Clearly, something spoke to them in Cognetti’s novel about male friendship, generational friction, the building of lives and the power of landscape to shape personal evolution. They even learned Italian in order to better immerse themselves in the project.

The Eight Mountains

The Bottom Line

Poignant but too slender for its epic length.

But in stretching a relatively slim novel into a contemplative 2½ hour drama, The Eight Mountains is a film that continually seems to be inching toward cathartic moments that prove evanescent, climbing toward summits it seldom reaches, if you will. It’s a pleasurable enough watch — nicely acted and with a gentle rhythm tuned to the main characters’ searching paths as they drift in and out of each other’s lives over 30 years — though ultimately, it lacks weight.

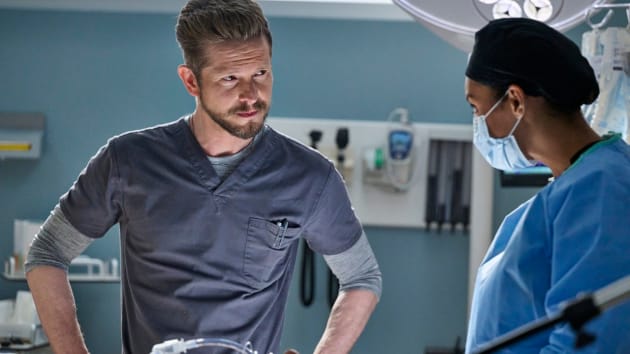

Intimately shot by Ruben Impens in the snug 4:3 aspect ratio, the film begins with the young Pietro (Lupo Barbiero), an only child about to turn 12, on vacation with his family from Turin in summer 1984 in a rustic village in the Italian Alps. He meets a boy of the same age, Bruno (Cristiano Sassella), who identifies himself as “the last child in the village,” which has shrunk in population from 183 to just 14 inhabitants. A road built for the purpose of bringing people there instead had the opposite effect.

Despite the differences between the citified son of a factory engineer and a schoolteacher and the unrefined cow-herder, whose father is constantly away working on construction sites abroad, the barriers between them instantly dissolve. For lonely Pietro, it’s a taste of freedom that seems almost as if he imagined it once he’s back in Turin.

But when he and his family return the following summer, Pietro and Bruno fall instantly back into their old friendship. The boys go hiking with Pietro’s father Giovanni (Filippo Timi), attempting to climb a glacier, and Bruno is impressed by the way Giovanni shares his knowledge, completely unlike his own taciturn father. Pietro’s mother (Elena Lietti) also helps Bruno with his schoolwork struggles. But when they offer to take him back to Turin and put him through high school, Bruno’s unseen father reacts angrily, whisking the boy off to learn construction work.

The two friends have no contact for 15 years, and Pietro grows moody and distant with his father, wounding him by accusing him of wasting his life. Only after Giovanni’s death does he return to the village (played in his 30s by Marinelli), discovering that his inheritance includes a parcel of land high up in the mountains with the ruins of a stone cabin, which Bruno (Borghi) has promised to rebuild.

That summer project, with Bruno bringing his construction know-how and Pietro providing labor, fortifies their bond. But it also opens Pietro’s eyes to the experiences he sacrificed by rejecting his father, who maintained contact with Bruno. In a touching thread, Pietro revisits a cairn on a mountain path where climbers sign a book nestled in the stones. He reads his father’s words of pride and happiness from their first hike there and then subsequent messages when Giovanni returned with Bruno in later years.

The divergent paths of the two friends keep pulling them apart — Bruno takes over his uncle’s mountain pasture, raising cattle and making cheese by traditional artisanal methods; he also meets a woman, Lara (Elisabetta Mazzullo), with whom he has a daughter. Pietro becomes a writer and goes traveling in Nepal, scaling other mountains and eventually forming a romantic attachment with Asmi (Surakshya Panta), a schoolteacher like his mother.

But Bruno’s financial troubles and the breakdown of his relationship with Lara draw Pietro back to try to help his friend, who berates himself for believing that a simple montanaro could run a business. Borghi is quite moving in those scenes, making Bruno bearish, angry and broken, and Marinelli (who drew attention in 2019’s Martin Eden) conveys the helplessness of being able to offer only temporary salves.

There are many affecting moments in the depiction of a sustaining friendship, nourished by nature and capable of withstanding long separations though inevitably insufficient to mend all of life’s difficulties. But van Groeningen and Vandermeersch have a tendency to fold some of the more dramatic turns into the story’s margins, making the film seem curiously underpowered, even as it deals with the pain of loss.

The use of Swedish singer-songwriter Daniel Norgren’s ambient score is effective, though the frequent neo-folky vocal tracks often feel like padding to provide emotional texture that should be more robustly woven into the storytelling.

In its reflections on love between men whose mutual understanding and place in the world are strengthened by natural settings, The Eight Mountains can’t help but recall Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy and First Cow. The new film has many admirable qualities, among them the serene beauty of the landscapes, but it needs more than that to help it withstand such comparisons.