A few years back, Mona Awad found herself in the grips of a skincare addiction. Hauling her laptop with her wherever she went, she watched video after video about Retinol and exfoliants, spellbound by the soothing voices and gently glowing faces of the skinfluencers on her screen. And she bought; she bought; she bought, whatever it was they were selling, whatever the price. This endless diet of Youtube tutorials and impulse buys left her “totally enchanted, but also suspicious and filled with dread,” Awad told me by phone from her home in Boston. “Which is always a good sign for me and means that I’m probably going to write a novel about it.”

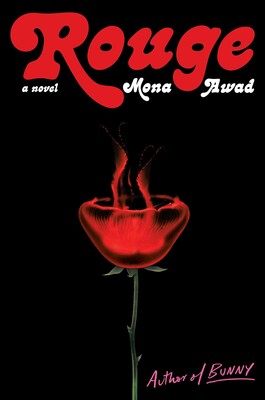

That’s exactly what she did. Rouge, Awad’s fourth novel, captures all the false hope and real self-hatred propagated by a beauty industry whose chokehold on women’s souls only tightens with each passing year. The story’s protagonist, Belle, has learned from a tender age that girlhood (and especially mixed-race girlhood) means loathing one’s own reflection. Her chief instructor in this lesson is her mother, a glamorous but frosty woman who models with her obsessive skincare routine the expensive, endless swim against the tide of wrinkles and sagging that will soon be Belle’s inheritance. When her mom dies under suspicious circumstances, a now-grown Belle begins to investigate the regimens and lotions that kept her mother’s skin preternaturally fresh. The literal cult that Belle discovers behind the scenes is equal parts dangerous and tempting. Who wouldn’t want to look forever young (and perhaps just a little bit whiter)? What wouldn’t one give?

Like Awad’s previous works Bunny, All’s Well, and 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, this latest novel is interested in the calamities and ecstasies we reap when we pursue our desires with desperation. Amidst its fairytale horrors, though (and believe me, Awad pulls no punches in the high Gothic intensity of the cabal’s beauty rituals), Rouge also tenderly explores grief, the psychic damage wrought by Eurocentric beauty standards, and the fierce, fraught love between mothers and daughters.

Chelsea Davis: Rouge is not just a story about the beauty industry writ large; it’s about skincare in particular. What drew you to writing about skin instead of hair or lips or body image more broadly?

Mona Awad: There’s just something so insidious about skin, and so intimate, and so horror. It’s this very, very, delicate protective covering of all this stuff on the inside. What does our obsession with the exterior, the surface, suggest about that interior? When you’re fixating so much on the surface of something seemingly so superficial as skincare, what are you avoiding?

I think a lot of what’s lurking behind skincare is anxiety about death. I started watching the videos and I was like, “Death is the thing we’re not talking about. We’re all on the edge of the abyss, putting our creams on.”

CD: There’s this beautifully jarring pair of sentences early in the novel that gets at exactly that—the way we run away from our own mortality towards an obsession with appearance. Belle is at the reception for her mother’s funeral, and says, “After the funeral. I’m hiding in Mother’s bathroom watching a skincare video about necks.” She’s in mourning, a state of extreme distress where she could be leaning on the people immediately around her for support. But she’s instead drawn like a moth to a flame to this skincare influencer she’s never met, on a screen.

MA: The fact that we are becoming more and more isolated makes us more vulnerable to whatever visual messaging we’re engaging with online or on our screens. That emphasis on the self will have consequences for our ability to connect with each other and see past ourselves. In Belle’s case, her loneliness makes her a target, the perfect candidate for La Maison de Méduse.

CD: Rouge is both a kind of fairytale in its own right and a meta-commentary on the genre. You also wrote a dissertation on fairytales, and your novel Bunny had elements of them. What about fairytales has such an abiding appeal for you?

The fact that we are becoming more and more isolated makes us more vulnerable to whatever visual messaging we’re engaging with on our screens.

MA: They are transformation stories at their core. They present the possibility of change, often to people who are powerless and wouldn’t have the means to change otherwise. And maybe the fairy tale indulges that longing for change—and then shows the shadow side, too. The fairy tales that are the most exciting to me will often present the wonder of transformation, but also the horror of it, the consequences.

The other aspect of fairytales that I love is that they present situations to us that I think are emotionally and psychologically resonant to a modern reader in a very real way—parent-child conflicts, issues with siblings, anxiety around sex and partnership, life changes—but they use a magical language of symbols to explore it. And I think part of why fairytales remain among the stories we keep coming back to across the centuries is because those motifs are so mysterious at their core. They’re elastic enough that you could cast them in a really sinister light, or you could cast them in a wondrous light. They will always ultimately elude being completely contained by any one meaning. And that is incredibly exciting as a writer. For instance, the mirror is highly mysterious in “Snow White,” and I was drawn to exploring its potential meaning in a story.

CD: It seems like another element of “Snow White” that your novel pulls in heavily is color. Both the original Grimm’s story and the Disney cartoon adaptation are characterized by a very strong palette of primary colors—red, yellow, blue, white, black. Red is flagged in your novel’s title, of course, and black and red are ubiquitous in the Maison de Méduse. Why was it important to you to inject this particular story with such a strong sense of color?

MA: Red, black, and white are the colors of folklore. And so emphasizing that color palette felt important to signal to the reader that we’re entering that kind of world. Also, in fairytales, red has a couple of different meanings, but certainly one of them is danger. So it’s a bit of a warning—but it’s also a lure, because it’s visually so attractive and it’s what’s right beneath the surface. The book might, at first glance, be interested in skin, but ultimately it’s interested in something deeper and more vital.

CD: What about that third color you mentioned as being crucial to Rouge: white? When people join the Maison de Méduse cult, they gain skin that is not just smooth and youthful, but specifically white.

MA: Snow White has such an interesting history in that sense. There are variants from all over the world. And in the Grimm version, Snow White’s whiteness is really more metaphorical; they never explicitly say that she is white-skinned. It’s the Disney version that gives us “skin as white as snow.” That was really interesting to me, that history of how Snow White becomes unequivocally, unambiguously white. And of course the object of such envy.

So Rouge became a story also about how beauty and whiteness are tied together in a very problematic way. That connection exists in the real-world beauty industry, too. As somebody who is of mixed ethnicity, an ethnicity that I share with Belle, I’ve always been really sensitive to that subtext—the idea of “brightening,” which is just a breath away from “lightening.” So race was definitely an aspect of beauty culture and the beauty industry that I wanted to have inform Belle’s own insecurity about her face and her skin.

CD: In pursuing whiteness and eternal youth through the cult, Belle ends up getting a lot more than she bargained for. That monkey’s paw plot structure is a common one across your novels: your protagonist gains something they want desperately, but at devastating cost. That “something” is a thin body, in 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl; in Bunny, it’s creative success. What do you find exciting about the Faustian bargain as a narrative setup?

MA: It’s my favorite dilemma because it’s at the heart of all fairytales. There’s a desire; there is a longing. Usually the person who has the longing is an underdog of some kind, and is not able to acquire the thing that they want. The Little Mermaid is a great example.

Fairytales are transformation stories at their core. They present the possibility of change, often to people who are powerless.

That careful-what-you-wish-for story connects us all because we all long for something that we think would make everything better. And I’m so interested in exploring that longing and of what it feels like to attain it—the wonder of attaining it, but also the really deep dread that might arise when it is not all that we hoped for. Because the longing is always a disguise for some other longing. Belle might long for great skin—but what does she really want? Connection with her mother; feeling accepted in the world that she finds herself in.

CD: Yes, that mother-daughter dyad is really at the dead center of Rouge. I was wondering whether the process of writing this novel clarified or complexified your understanding of your relationship with your own mother.

MA: In some ways it did. I was really interested in the dynamic in which a mother knows she is going down a destructive path, but can’t keep herself from doing so. And her daughter is watching her go down this path, and wants to follow. The mother doesn’t want her daughter to experience the damage that she’s already experienced herself. But it’s already too late.

And the mother’s navigation of that in Rouge, the ways that she tries and fails to protect her daughter from the irreversible damage she herself has undergone—for me, just thinking about my own mother, and thinking about my mother’s relationship to her mother, that was really meaningful to explore that in the story. It helped me understand just how difficult that might be. You don’t want to harm someone by doing harm to yourself, but you still might, against all your good intentions. That’s just the nature of parent-child relationships.

CD: A young daughter is like a mirror, in that sense. She’s taking in everything you do.

MA: Yes, that’s right. Including the beautiful things, too. I really wanted to do justice to each of these two characters, the mother and the daughter. To present the truth of both experiences, even as we’re looking at the world of the story through the daughter’s eyes.

CD: Both the mother and daughter eventually succumb to the same shady skincare cabal, and both experience, as a result of those spa treatments, gradual memory loss. A significant stretch of the novel is narrated by Belle as she’s experiencing this and other forms of cognitive impairment. What it was like to write a story through the perspective of someone whose memory is deteriorating?

MA: I’m fascinated by altered states of consciousness. I love reading stories where the character’s mind is altered in a way that’s reflected in how they’re telling us the story, because we can see things that they can’t. That’s a great pleasure for the reader, to know things that the main character does not.

It was both fun and scary to write Belle in such a state. I teach a class on horror, and of course, there are many possession stories in that genre. So the idea that what’s on the outside might be seeping inside and changing Belle, altering her consciousness, is a nightmare. And the worst part of the nightmare is that she’s not fully aware that it’s happening to her. That’s the most terrifying part of possession: if you’re truly possessed, you don’t know it. I wanted to explore what that might feel like.

But beyond the supernatural element at play, Belle’s changing mind was also a way of exploring a real-life fear that I have. Memory loss is something that could happen to any of us any time; you could somehow lose your grip on your understanding of who you are.

CD: It sounds like you often write directly into your fears.

MA: Yeah, I do. That’s where the heat is. For me, it’s the engine of creativity—fear and longing, together. I love asking the question, “what if?” I can make my own horror novel just sitting in the dark by myself. I’ll really scare myself in the process, but I’ll probably have fun, too.

CD: On the flip side, since you’re often writing about your own anxieties, do you find that there’s any personal catharsis at the end of the process of writing a novel like this? For example, are you in a different place with regard to skincare and beauty after writing Rouge than you were beforehand?

MA: Ultimately, there is catharsis whenever I feel like I’ve written a scene that is really meant to be in the story. But then there is a feeling of great loss when it’s all over because I’ve lived inside of this world for two or three years. I’ve completely inhabited it. It’s been the place that I go in my mind. And when it’s finished, there’s no place to go. And so I have to go through a real period of grieving, actually, when it’s over.

Rouge was particularly hard to let go of, in terms of how it changed my view of skincare. I mean, when I first finished the book, I had no desire to watch skincare videos ever again. [Laughs.] And then I wrote a piece about my skincare addiction for a Canadian magazine called The Walrus, and so I had to revisit some of those videos. And when I started watching again, I got hooked again. I bought all these products that I can’t afford, that I won’t use, that I definitely don’t need. So it truly was an addiction. I thought I was going to be so above it. But I’m not above anything.

CD: I mean, you’re not alone. In the age of Instagram, and casual filler, and twenty-year-olds getting into Retinol, it’s easy to feel like our culture’s obsession with appearance is only getting more inescapable. Do you, or Rouge, hold out any kind of hope for ways out of the trap?

MA: Without giving too much away, I think that the novel does offer ways to find connection in isolation, either through mutual trauma or sharing trauma, which is something that I think can be very meaningful. And in fact, social media might be a way to do that—already is, for many people. But that connection can also happen through art, through sharing stories. Being both the reader and the audience, both the teller of the story and the listener. I think that is the way forward. Or at least that’s my hope.