Our ancestors’ big break came 66 million years ago, on the worst day in Earth’s history. An asteroid slammed into our planet, set off tsunamis and volcanoes and wildfires, and darkened the skies for years. The disaster was the end of the dinosaurs (aside from birds) but a new beginning for mammals—or at least the mammals that survived. In our cover article, paleontologist Steve Brusatte fills out this origin story with fascinating new details about the mammals that thrived in the Before Times and a deeper understanding of how some survived into the After.

Childhood development is one of the richest and most productive fields of research today—there’s just so much happening from birth through the first several years of life. The brain expands rapidly and builds a million connections per second, as children learn languages and social connections and how to explore the world. As childhood-learning researcher and physician Dana Suskind and writer and Scientific American contributing editor Lydia Denworth explain, research has identified two crucial factors that encourage healthy cognitive development: protection from stress and nurturing interactions with caregivers. The work they share has urgent implications for policies that help children thrive.

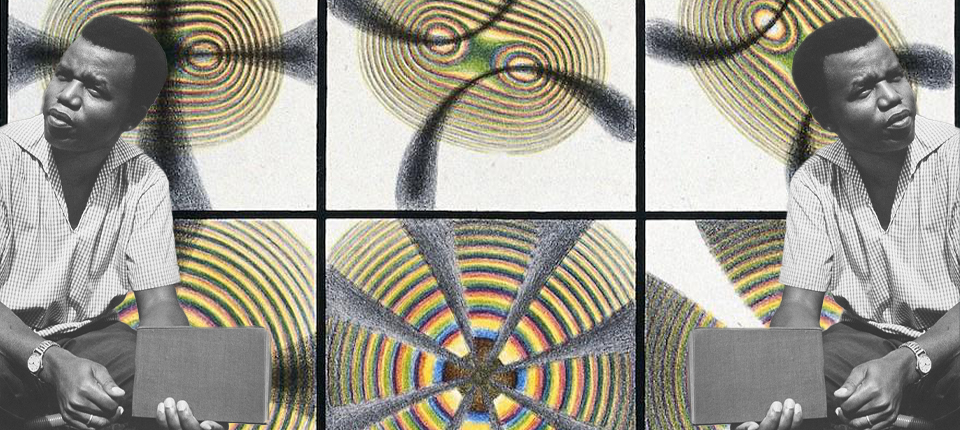

Going deeper into how the brain learns to understand the world, neuroscientist György Buzsáki presents an “inside-out” theory of brain functioning. The classic “outside-in” conception holds that the brain starts as a blank slate and gets inscribed by perceptions and experience. But the brain has its own ideas about how to organize, generalize and respond to external stimulation. Studies in people and animals and AI research show how the brain’s internal algorithms can be used to shape our experiences, plan ahead and learn efficiently.

Powerful flares called fast radio bursts erupt with as much energy in an instant as our sun emits in a month. Astronomers aren’t sure what causes the flashes, but they made a lot of progress when an especially energetic fast radio burst in 2020 was traced back to a magnetar, an enormous remnant of a supernova. Not all fast radio bursts seem to come from magnetars, though, and some may be repeaters rather than single explosions. It’s a hot area of astronomy, as science writer Adam Mann describes, and it’s poised to get hotter—fast radio bursts might help reveal what matter they traveled through from their origins to our telescopes.

A fundamental injustice of modern times is that privileged people live longer, healthier lives than people who face discrimination, disempowerment and systemic bias. Our special package on health equity explains what we know about disparities in our health systems and, more important, how to fix them. Heart disease, the leading killer worldwide, is even more deadly in disadvantaged groups. The world’s oldest pandemic, tuberculosis, has been largely eliminated in the wealthy world but persists in poverty. Mental health care should be a right, not a privilege. And you will meet people who are finding solutions to health inequalities across the globe and who are drawing still relevant lessons from the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

All of us at Scientific American thank Curtis Brainard, our managing editor, for leading the health equity package in this issue and so many other innovations and projects. Curtis joined our publication in 2014 as the blogs editor and soon began overseeing all our online content. He became managing editor in 2017 and acting editor in chief in 2019 and got us through the beginning of the COVID pandemic. Curtis is leaving Scientific American (reluctantly, he says) for a sweet new job in Paris, and we all wish him well, but gosh, we’re going to miss him!