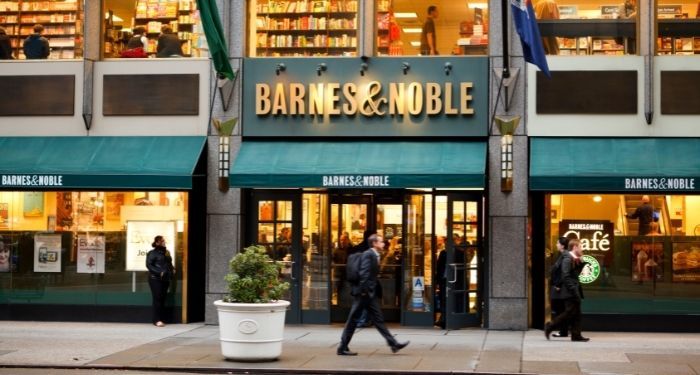

A slow-motion crisis is unfolding in the commercial real estate market, thanks to the double-whammy of higher interest rates and lower demand for office space following the Covid-19 pandemic.

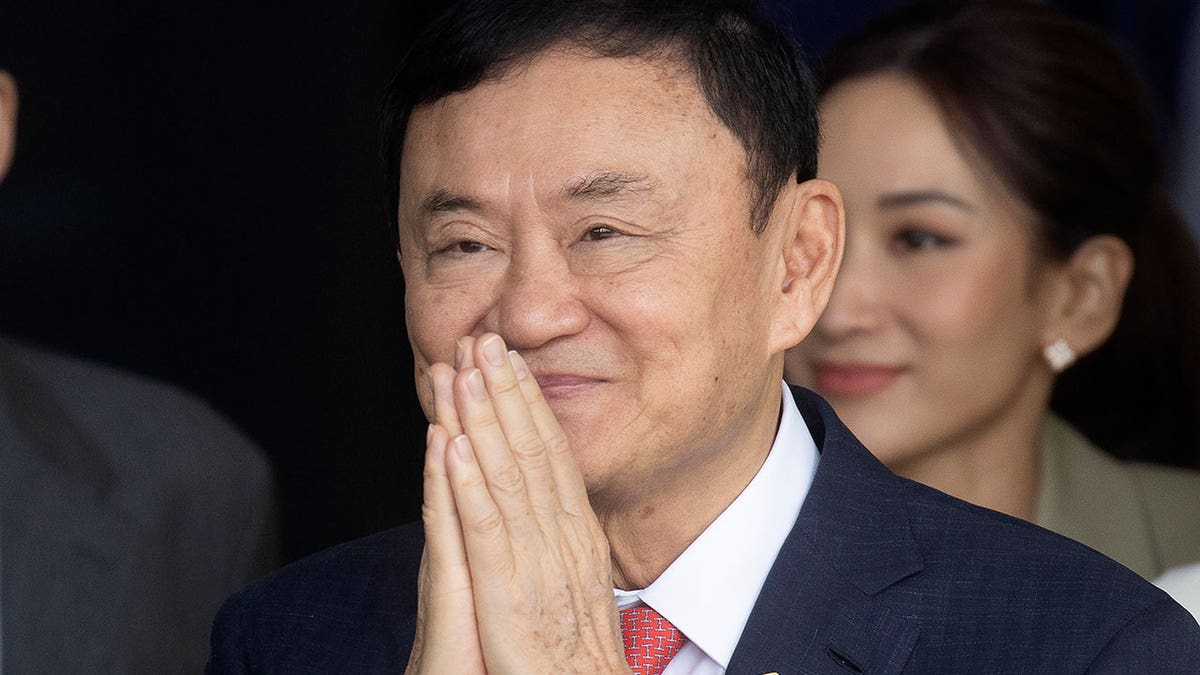

John Fish, who is head of the construction firm Suffolk, chair of the Real Estate Roundtable think tank and former chairman of the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, joined the What Goes Up podcast to discuss the issues facing the sector.

Below are some highlights of the conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity. Click here to listen to the full podcast.

Q. Can you talk to us about why this rise in interest rates that we’ve experienced is so dangerous to this sector?

A. When you talk about these large structures, especially in New York City, you get all these buildings out there, almost a hundred million square feet of vacant office spaces. It’s staggering. And you say to yourself, well, right now we’re in a situation where those buildings are about 45%, 55%, 65% occupied, depending where they are. And all of a sudden, the cost of capital to support those buildings has almost doubled. So you’ve got a double whammy. You’ve got occupancy down, so the value is down, there’s less income coming in, and the cost of capital has gone up exponentially. So you’ve got a situation where timing has really impacted the development industry substantially.

The biggest problem right now is because of that, the capital markets nationally have frozen. And the reason why they’ve frozen is because nobody understands value. We can’t evaluate price discovery because very few assets have traded during this period of time. Nobody understands where bottom is. Therefore, until we achieve some sense of price discovery, we’ll never work ourselves through that.

Now, what I would say to you is light at the end of the tunnel came just a little bit ago, back in June when the OCC, the FDIC and others in the federal government provided policy guidance to the industry as a whole. And that policy guidance I think is very, very important for a couple reasons. One, it shows the government with a sense of leadership on this issue because it’s this issue that people don’t want to touch because it really can be carcinogenic at the end of the day. It also provides a sense of direction and support for the lending community and the borrowers as well. And by doing such, what happens now is the clarity.

Basically what they’re saying is similar to past troubled-debt restructuring programs. They’re saying, listen, any asset out there where you’ve got a qualified borrower and you’ve got a quality asset, we will allow you to work with that borrower to ensure you can re-create the value that was once in that asset itself. And we’ll give you an 18- to 36-month extension, basically ‘pretend and extend.’ Whereas what happened in 2009, that was more of a long-term forward-guidance proposal and it really impacted the SIFIs (systemically important financial institutions). This policy direction is really geared toward the regional banking system. And why I say that is because right now the SIFIs do not have a real big book of real estate debt, probably less than 8% or 7%. Whereas the regional banks across the country right now, thousands of them have over probably 30% to 35% and some even up to 40% of the book in real estate. So that guidance gave at least the good assets and the good borrowers an opportunity to go through a workout at the end of the day.

Q: This “extend and pretend” idea seems to me almost like a derogatory phrase that people use for this type of guidance from the Fed, or this type of approach to solving this problem. But is that the wrong way to think about it? Is “extend and pretend” actually the way to get us out of this mess?

A: Let me say this to you: I think some well-known financial guru stated that this was not material to the overall economy. And I’m not sure that’s the case. When I think about the impact that this has on the regional banking system, basically suburbia USA, we had Silicon Valley Bank go down, we had Signature Bank go on, we saw First Republic go down. If we have a systemic problem in the regional banking system, the unintended consequences of that could be catatonic. In addition to that, what will happen is when real-estate values go down? 70% of all revenue in cities in America today comes from real estate. So all of a sudden you start lowering and putting these buildings into foreclosure, the financial spigot stops, right? All of a sudden, the tax revenues go down. Well, what happens is you talk about firemen, policemen and teachers in Main Street, USA, and at the end of the day, we’ve never gone through something as tumultuous as this. And we have to be very, very cautious that we don’t tip over the building that we think is really stable.