As the war rolled on, organizations responding to the crisis came to realize that they had to be flexible and think beyond fixed, brick-and-mortar health care infrastructure. They needed to get ART to people—interrupted treatment can contribute to drug resistance—and they needed to continue, and scale up, harm reduction programs.

Andriy Klepikov, the executive director of the Alliance for Public Health, a nonprofit organization that focuses on HIV and tuberculosis, says his teams deployed 37 mobile clinics from Lviv in the west to Kharkiv in the northeast, providing more than 109,000 consultations, testing more than 90,000 people for the communicable diseases, delivering close to 2,000 metric tons of humanitarian aid and medical gear to 200 health care facilities, and connecting with small villages that would otherwise have been abandoned to their fate.

Equipped with bulletproof vests, helmets, and metal detection gear, the Alliance’s staff headed into recently liberated cities and villages, some only a few kilometers from the front line. “We work where nobody else works, where there are no hospitals, no pharmacists, no doctors,” Klepikov says.

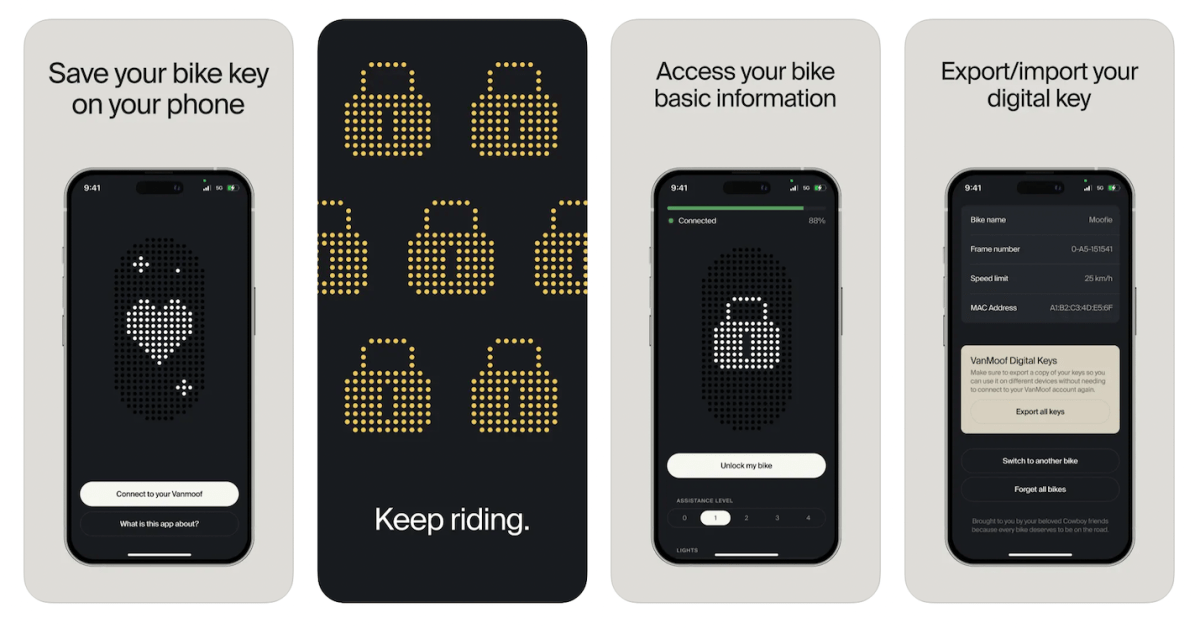

When fuel became hard to find last summer, they switched their vans for bicycles. In his office in Kyiv, Klepikov proudly showed me a photo of one of the Alliance’s doctors hand-delivering care in a shelled-out city while riding one of the bikes his organization had provided.

Preliminary data shows that disaster has—for now at least—been averted. At the end of 2021, just two months before the war began, about 132,000 Ukrainians living with HIV were on ART. Since then, the latest available figures show that this number has only slightly dipped to 120,000. Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s public health sector has connected 12,000 new people to ART. That latest available data from February 2023 also shows that during 2022, more people began taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) than in the previous four years.

These successes have come at great personal cost. Rachinska, who has herself been living with HIV for more than 15 years, kept working in Kyiv as air raid sirens echoed through the capital. Her mother took Rachinska’s youngest son and fled to Italy. She’s visited him only a couple times since then but hopes she’ll make it back to Naples this October, ahead of his 11th birthday.

Rachinska could have joined them but says her work—“her people,” as she calls them—takes priority. Her son doesn’t hold it against her, she says. “I’m just like, ‘sweetie, mommy’s doing something good for people. So just forgive me,’” she says, tearing up. Her son often replies, “OK, do your job.”

In Kryvyi Rih, Lee, 47, says he created his makeshift sanctuary after realizing early in the war that at-risk populations, such as drug users, HIV-positive people, sex workers, LGBTQ+ people, and the recently incarcerated were more likely to be turned away from other spaces offering refuge. He secured funding from UNAIDS and logistical support from the Public Health Charity Foundation and set out to rescue people on his own.