Electric Literature recently launched a new creative nonfiction program, and received 500 submissions in just 36 hours! Now we need your help to grow our team, carefully and efficiently review submitted work, and further establish EL as a home for artful and urgent nonfiction. We’ve set a goal of raising $10,000 by the end of June. We’re almost there! Please give what you can today.

The patriarchy is always on the offensive: yesterday’s reproductive rights can be reduced today and might even be gone completely tomorrow, forcing us to return to the same old struggles, too busy surviving to even think of bigger demands. We are now more worried about the prospect of A Handmaid’s Tale-style life than we are looking forward to a brighter future.

Narrow definitions of womanhood function the same way: they rob women of options, of their humanity. They compress their priorities, causing women to lose sight of what they actually want, of their agency. Tender and nurturing? Yes. Cold-blooded murderers and serial killers? Absolutely not. If they do kill, they better have a good reason. It is dehumanization disguised as virtue.

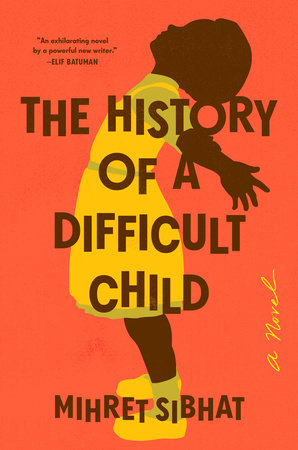

My debut novel, The History of a Difficult Child, has a number of bad-mannered women inspired by members of my family. I come from a line of women with a history of beating up their abusive husbands, snatching a policeman’s gun, walking about town in the evenings carrying spears. While I do not wish to ever be in a position of having to beat up someone, if it comes down to a future of forced procreation in America, I, a lesbian, wish to be the one who births the Anti-Christ.

The books on this list recount the stories of women who breach those narrow boundaries of womanhood through the commission of violence or the embrace of rudeness and disorder and dirt or a descent into darkness, returning with seismic realizations that could turn the tamest woman into a killing machine.

Egypt: Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi

Firdaus feels no remorse for murdering her pimp. In the prison cell where she awaits execution, she recounts her tribulations, beginning with a childhood of abuse and neglect to an adulthood of violence and betrayals. The ceaseless assault on her body and spirit compresses her sense of identity to such an extent that, at some point, she can’t tell if she prefers oranges to tangerines. She is still relentless about seeking a better life: she runs away, stands her ground, and fiercely pursues love and the hope it carries. At every turn, she is stifled by the men who serve as proud foot soldiers of the patriarchy. In the end, she and those around her realize she is different—not because she murders a man, as there are other women who have done so—but because of her earth-shattering realizations about how women should relate to men. “That is why they are afraid and in a hurry to execute me. They do not fear my knife.”

Italy: The Dry Heart by Natalia Ginzburg

“I shot him between the eyes,” the narrator tells us of her husband, Alberto, before going to the cafe to recollect herself. This is a story of a man and a woman whose lives are poisoned by patriarchal expectations. Before marriage, they are friends who spend a lot of time enjoying each other’s company, going to the theater, laughing. She tells him she is in love with him, not because she really loves him but because she likes the idea of him and of a marriage. He tells her he doesn’t love her—he loves a woman who is married to someone else—but marries her still because he wants the same things. Despite his initial honesty, he lies to her about the trips he takes to see his mistress, feeling no obligation to be decent, for he is no longer his wife’s friend but a mere prop in a marriage play. How do they escape such a state of dehumanization?

Antigua: A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid

In this explosive book, a hypothetical tourist visiting Antigua is yanked out of his fantasies by a tour guide he didn’t ask for—Jamaica Kincaid. There’s nothing innocent about his visit, he learns, and that everything has been polluted by colonial violence, capitalism, and corruption. The beautiful ocean he has imagined swimming in for so long is full of things one shouldn’t swim with. There are even questions about the neutrality of the taxicab that drives him to his hotel. The notion of the friendly native who greets tourists with an everlasting smile is shattered. As a Black woman, Kincaid is supposed to be extra polite and grateful to this white man who has come from “North America (or worse, Europe)” for taking interest in her island. And yet, she makes him into an “ugly” and “empty” villain, and regales us with a delicious ideation of terrorism: “Do you ever wonder why some people blow things up? I can imagine that if my life had taken a certain turn, there would be the Barclays Bank, and there I would be, both of us in ashes.”

Zimbabwe: The Book of Memory by Petina Gappah

A Cambridge-educated albino woman, Memory, finds herself convicted of the murder of her adoptive father. As she appeals to overturn her death sentence, she recollects the events of her childhood in letters to a journalist. She is othered as a child, bullied by children, avoided by adults who fear she carries evil forces. Later, her attempts to find love are shattered by betrayals. In prison, she begins using writing to decompress events and make sense of them, recover lost memories, and expand her understanding of herself and those around her. She turns her cell into a room of her own. And when new discoveries shatter the foundations of her beliefs about her life, writing and the solidarity she finds among other women prisoners and employees keep her grounded.

Italy: The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante

Olga grows up with a severe fear of becoming one of those women who “broke like knickknacks in the hands of their straying men.” As a child, she watches “a large, energetic” neighbor disintegrate after being left by her husband. From her mother, she learns that this problem of women being devastated by abandonment is widespread. So, she prioritizes her husband’s career over hers. She avoids “raised voices, movements that were too brusque” and learns “to speak little and in a thoughtful manner.” When her husband leaves her anyway, she tells herself not to be like that poverella of her childhood. The darkness doesn’t seek her permission as it drags her down and, in her descent, she becomes crass and paranoid, the kind of woman who terrifies her own children and alienates her friends. Like that poverella. At her lowest moment, she defecates in the vegetation at the neighborhood park. This is a story of a woman who walks through fire to learn the meaning of solidarity and, in doing so, finds her voice.

Zimbabwe: Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga

Our young narrator, Tambu, begins her story with a confession: “I was not sorry when my brother died.” She lives in a village with her family, helping out on the farm, herding the cows, fetching water, and cooking. The family sends her and her older brother, Nhamo, to school, but Nhamo gets the better deal: he goes to the mission school where his foreign-educated uncle is the principal and lives in a comfortable house with running water. Tambu’s education is not guaranteed as there’s not always enough money to pay the fees for the local school, and her father tells her to focus on learning the skills she needs to be a good wife. Nhamo is increasingly detached from his family in the countryside. When he visits during school breaks, he contributes little and abuses his little sister.

Despite witnessing her brother’s inability to be transformed by education, Tambu latches onto the hope that there is a better life to be gained through education. Look at her uncle’s educated wife. When Tambu leaves the village to attend the mission school and later to a better one, she realizes that even as one moves across class borders, women’s status remains one of alienation, and that race further complicates and increases that alienation. She excels in the classroom but her liberation comes from the piercing clarity she gains about family and her own place in the world.

Nigeria: My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

Korede spends her day keeping order at the hospital where she’s a supervisor nurse. By night, she’s cleaning after a younger sister with a penchant for stabbing her boyfriends to death. The knife Ayoola uses to cut her boyfriends was inherited from a father whose only moments of tenderness were spent on the cleaning of that tool, which he guarded so fiercely that he once threw Ayoola at the wall for smearing it with chocolate. Korede doesn’t know what to do with her sister, who claims that she only kills in self-defense. But where are the wounds, the bruises? Still, Ayoola calls her big sister after every kill and Korede arrives with the material and expertise required to clean the crime scene of “all trace of life” and dispose of the body. What to do then? Should she go to the police? Should she at least cut her sister out of her life? This is a story about the meaning and limits of sisterhood and solidarity in a patriarchal world.