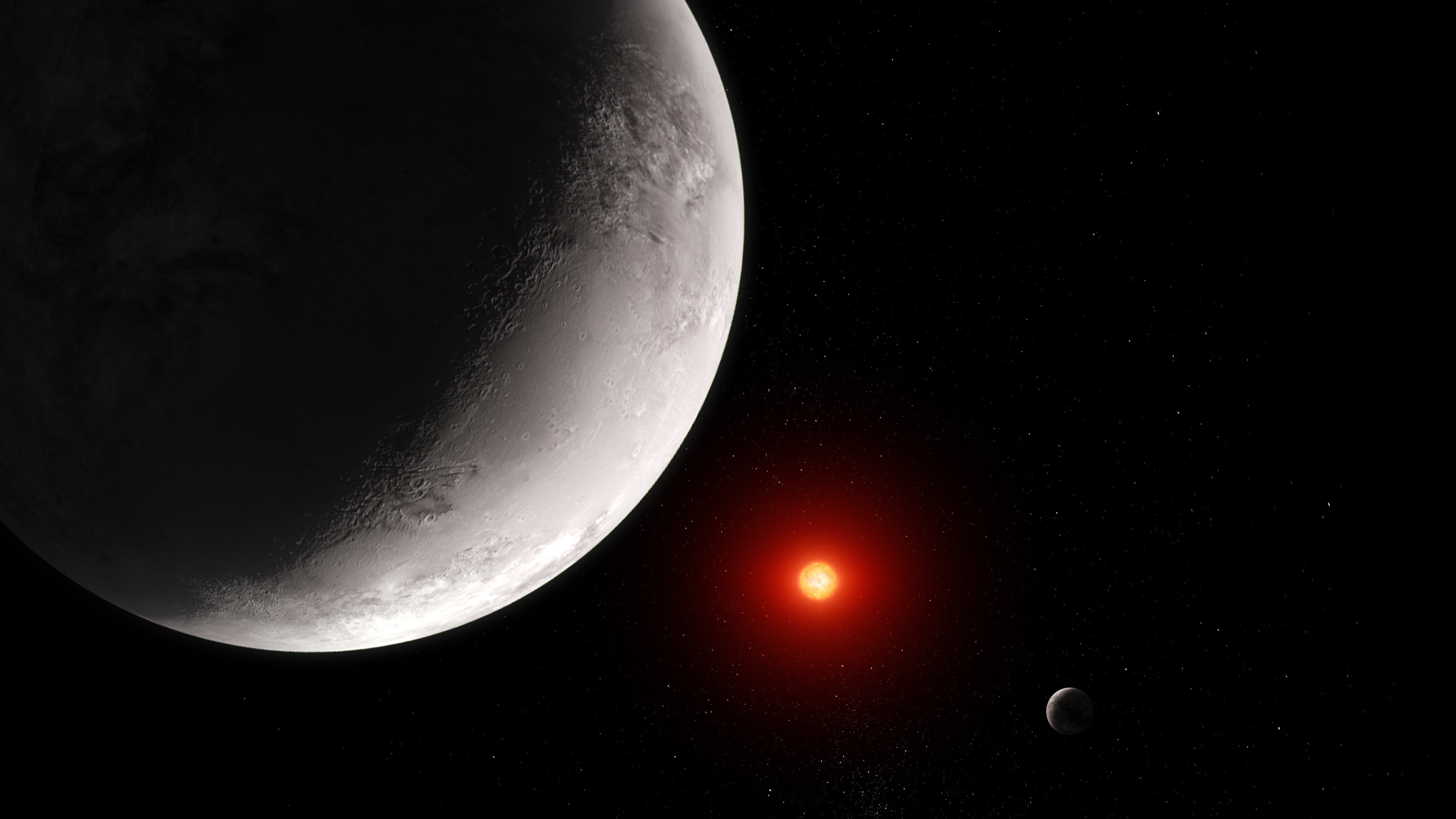

For the second time, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has looked for and failed to find a thick atmosphere on an exoplanet in on one of the most exciting planetary systems known. Astronomers report today that there is probably no tantalizing atmosphere on the planet TRAPPIST-1 c, just as they reported months ago for its neighbour TRAPPIST-1 b.

There is still a chance that some of the five other planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system might have thick atmospheres containing geologically and biologically interesting compounds such as carbon dioxide, methane or oxygen. But the two planets studied so far seem to be without, or almost without, an atmosphere.

Because planets of this type are common around many stars, “that would definitely reduce the amount of planets which might be habitable”, says Sebastian Zieba, an exoplanet researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. He and his colleagues describe the finding in Nature.

System with star power

All of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets, which orbit a star some 12 parsecs (40 light years) from Earth, have rocky surfaces and are roughly the size of Earth. Astronomers consider the system to be one of the best natural laboratories for studying how planets form, evolve and potentially become habitable. The planets are a key target for JWST, which launched in 2021 and is powerful enough to probe their atmospheres in greater detail than can other observatories such as the Hubble Space Telescope.

The planets’ host star is a dim cool star known as an M dwarf, which is the most common type of star in the Milky Way. It blasts out large amounts of ultraviolet radiation, which could erode any atmosphere on a nearby planet.

The system’s innermost planet, TRAPPIST-1 b, is blasted with four times the amount of radiation that Earth gets from the Sun, so it wasn’t too much of a surprise when JWST found that it had no substantial atmosphere. But the next in line, TRAPPIST-1 c, orbits farther from its star, and it seemed possible that the cooler planet might have managed to hang on to more of an atmosphere.

Zieba’s team pointed JWST at the TRAPPIST-1 system four times during October and November, allowing the scientists to calculate that TRAPPIST-1 c’s surface temperature, on the side that faces its star, registers at around 107 °C — too hot to maintain a thick atmosphere that is rich in carbon dioxide.

Low-water mark

By comparing the observations with models of the planet’s possible chemistry, the scientists also concluded that TRAPPIST-1 c would have had very little water when it formed — less than ten Earth oceans’ worth of water. Together, the low amount of water at the planet’s birth and the lack of a thick carbon dioxide atmosphere today suggest that TRAPPIST-1 c never had many ingredients for habitability.

But there might still be hope for other planets in the system. In a paper posted on 8 June on the arXiv preprint server, Joshua Krissansen-Totton, a planetary scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, reported that the TRAPPIST-1 planets e and f — the fourth and fifth farthest from the star — could still have thick atmospheres, because they sit far enough away from the star to avoid having all of their water blasted away, unlike planets b and c.

In other words, what scientists find on planets b and c might not say much about what the atmospheres of the outer planets could look like. “I think it makes sense to remain agnostic on the prospects for the outer planets retaining atmospheres,” Krissansen-Totton says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on June 19, 2023.

![‘Survivor 47’ Finale Recap Part 2, [Spoiler] Wins ‘Survivor 47’ Finale Recap Part 2, [Spoiler] Wins](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/survivor-finale-part-2-cbs.jpg?w=650)