Women’s achievements have long been overlooked in the annals of history, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the field of science. When I first began digging into the history of nineteenth-century geology for my novel Our Hideous Progeny, I was shocked to find how many women were actually working in the field, considering how scarcely their names crop up in textbooks. Without access to formal education, many of these women either taught themselves or became involved in science by acting as assistants to their male relatives, learning on the job and often making significant discoveries in their own right. Indeed, many well-known and prolific scientists in recent history were enabled by women, who acted not only as their lab assistants and scientific illustrators, but also as their editors, translators, housekeepers, child-minders, and travel agents.

Even now, many women around the world are still denied access to education, and female scientists and academics have had to fight every step of the way for access to the same pay and recognition as their male peers. Although there is still a long way to go, modern historians, writers, and crowd-sourced efforts like Wikipedia Edit-a-Thons have made considerable progress in finally recognizing the women scientists whose work has long been overlooked.

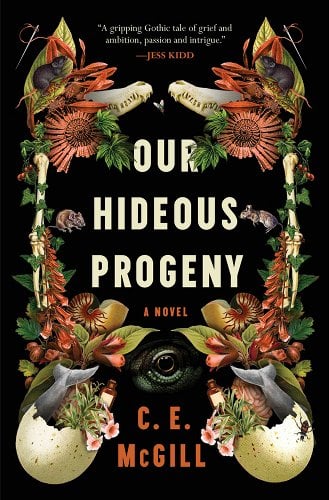

As a nonbinary person and former engineering student, uncovering the real diversity of the history of science has always been important to me. The vast majority of scientists I read about as a child, in history books and in the science fiction stories I loved, were straight, cisgendered men; it took me years to discover Ada Lovelace, Katherine Johnson, Sally Ride, James Barry, and other role models who broke the mold. So, when I realized that I wanted to write a book that combined my love for nineteenth-century science with Frankenstein—transposing the fascinating themes of Mary Shelley’s classic into the turbulent world of 1850s paleontology—I knew that my main character had to be a Mary, not a Victor. Fortunately, Mary is in fantastic company, as novels honoring the work of women in science are now being more frequently published. Below are just some of my favorites.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

In the 1980s and the world of computer science, this story follows dual protagonists Sadie and Sam, who meet in the hospital as children and bond over a shared love of video games. Later, as college students, they meet again by chance and decide to collaborate on a video game of their own. But turning the thing they love into a means of making money means facing the prejudices of the game industry, like when a large studio offers to produce their game—but only if they make their intentionally genderless protagonist male. Not to mention, as the game becomes a runaway success and the team suffers several tragic setbacks, Sam (the male developer) becomes the public face of the project and Sadie receives little credit for the code she contributed. While neither character is without their flaws, and their relationship is complicated, Zevin brings them together for a nuanced story about the challenges of creative collaboration, the escapist power of video games, and the gendered difficulty associated with receiving one’s due.

The Tenth Muse by Catherine Chung

In this compact but powerful novel, set in the decades after World War II, we meet Katherine, a young Asian American woman determined to make her place in the world of mathematics. From an early age, Katherine’s parents foster in her a love of nature and science—but after her mother abruptly abandons the family one day, Katherine buries her hurt and confusion in her studies, eventually becoming fixated on proving the notorious Riemann Hypothesis. As it turns out, however, the Riemann hypothesis and her own family history are far more entangled than she knows, and Katherine finds herself journeying across Europe in search of the truth. I adored the way that Chung depicted the struggles that women (especially women of color) face in STEM—not just outright prejudice, but also loneliness, insecurity, and a complicated mix of inspiration and envy that comes from seeing someone else like you succeeding in your field. Plus, as a fan of mathematics myself, I thoroughly enjoyed seeing a character as driven and interesting as Katherine so passionate about the beauty and grace of a good equation.

Remarkable Creatures by Tracy Chevalier

This fascinating and introspective story covers the friendship of Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot, two real-life paleontologists of the nineteenth century. In the fossil-rich town of Lyme Regis, the Anning family made their living selling fossils to tourists and collectors, but Mary was the first in her family to appreciate the scientific importance of these objects and educate herself in paleontological classification. Elizabeth Philpot, originally from a well-to-do London family, moved to Lyme Regis and developed a fascination with fossil fish, through which she and Mary Anning forged a lifelong friendship. Chevalier does a fabulous job of exploring the religious and existential quandaries stirred up by the nascent science of paleontology, as well as the different ways in which gender and class affect the two friends’ lives: as a woman of some standing, Elizabeth is allowed scientific hobbies but will never be considered a professional; and as a working class woman, Mary is respected for her practical ability to find fossils, but never as a true contributor of scientific knowledge.

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

This introspective novel follows Gifty, a Ghanaian American student of neuroscience living in Alabama. Gifty’s parents immigrated to America before she was born in search of better opportunities for their future children; faced with poverty and racism, however, the family struggled, and Gifty’s father eventually returned to Ghana, claiming it was only a visit – though he never came back. Tragically, the family was wounded further when Gifty’s older brother, a talented high school athlete with a bright future ahead of him, addicted to opioids after a training injury, falling into addiction and eventually dying of a heroin overdose. Now, in the present, Gifty’s mother barely leaves her bed, near-catatonic with grief, and Gifty focuses herself on her research, trying to use science to make sense of the misfortunes her family has suffered. Compelling and full of emotion, this fascinating novel asks complex questions about grief, religion, and the workings of the human mind.

The Fair Botanists by Sara Sheridan

This novel follows another Elizabeth, the recently widowed Elizabeth Rocheid, who arrives in Edinburgh in the 1820s. An eager botanist and artist, she offers her services as an illustrator to capture the once-in-a-lifetime flowering of the Agave Americana plant in the city’s brand-new Botanic Garden. Along the way, Elizabeth strikes up a touching friendship with Belle Brodie, a fellow botany enthusiast (whose interest in the rare flower, however, runs in a far more commercially-exploitable direction). With plenty of cameos from famous scientists and thinkers of the era, Sheridan skillfully captures the buzz and excitement of this period of scientific history, painting a fascinating portrait of the Botanic Garden and Georgian Edinburgh as a whole.

The Echo Wife by Sarah Gailey

In this fast-paced sci-fi thriller, geneticist Evelyn Caldwell is the pioneering scientist behind a new cloning technology that can be used to replicate already-existing humans with complete accuracy—at least, in terms of their physical form. When Evelyn creates a clone of herself named Martine, her husband decides that he actually prefers the personality of the clone, and leaves Evelyn for Martine. Forced to confront the ethical quandaries brought about by the technology she has created, and the long-standing flaws in her marriage, Evelyn’s life is thrown into disarray. Suspenseful yet also filled with deeper questions about personal autonomy and identity, The Echo Wife asks if we really know our loved ones as well as we think we do.

The Calculating Stars by Mary Robinette Kowal

Set in an alternate 1950s in which the Eastern US is devastated by a meteorite and the resulting global warming necessitates the human colonization of space much earlier than planned, this novel follows Elma York, a brilliant mathematician and former WWII WASP pilot. Elma works as a computer at the International Aerospace Coalition (think: NASA), and despite her debilitating anxiety around reporters, her tireless campaigning for women to be included in the space program shoves her into the public eye as “The Lady Astronaut.” Kowal’s exhaustive research into the history of space travel shines in this novel, and touches on many aspects of real history, including the (sadly short-lived) female astronaut training program of the 1960s. In some ways, Kowal’s version of the 50s is almost better than ours, as the necessity for international cooperation requires that scientists of different races and nationalities be included in the space program far sooner than they were in reality. However, it is still the 1950s, and Elma’s Black colleagues, in particular, face countless obstacles. Elma, as a Jewish woman, is no stranger to prejudice herself, and finds solace throughout the difficulties she faces in her faith, community, and wonderfully supportive husband.

The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins

Beginning in the middle of a murder trial, this razor-sharp and beautifully written novel follows the life (and confessions, as the title suggests) of Frannie Langton. We meet Frannie as a domestic servant in early nineteenth-century London when she is accused of brutally killing her employers, a respected scientist and his wife—though she claims she cannot remember whether she did so or not. Through Frannie’s tense and atmospheric narration, we learn that she was originally born as a slave on a Jamaican plantation, where she was educated and taught to assist with her master’s scientific experiments, but at a terrible price. Based upon the real and horrifying history of medical experimentation on Black (and frequently enslaved) people, Collins sheds light on the ugly underbelly of nineteenth-century science, much of which was founded upon racist ideas and funded by colonialism. Evoking the best of the Gothic tradition, Collins’ prose brings Frannie (and her complicated and compelling relationship with her English mistress, Marguerite) utterly to life. I was glued to every page.

Chemistry by Weike Wang

Sharp and thought provoking, Chemistry follows a young Chinese American student grappling with the expectations of academia, society, and her demanding parents. At first glance, our unnamed narrator seems to be on the perfect track to a successful and happy life: she’s studying for a PhD in chemistry, and her wonderful boyfriend just proposed marriage. But in reality, she’s overworked, riddled with stress, and unsure whether she wants to marry at all. Her PhD has already dragged on for several years—much to her and her parents’ frustration—and the question of whether she actually enjoys chemistry is impossible to disentangle from the heavy burden placed on her as a “model minority” and child of immigrant parents. Through the eyes of this anxious young student, Wang explores the immense pressure on women (particularly women of color) to prove themselves worthy of their place in academia.