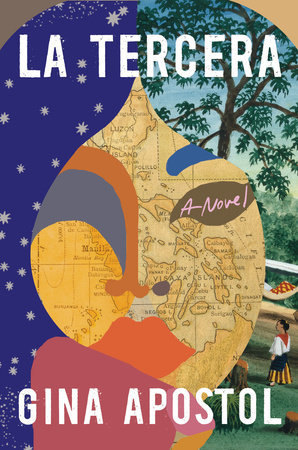

To say that Gina Apostol’s prose is pyrotechnical is to state the obvious: juggling an immense cast of characters, decades of political entanglements, and Apostol’s trademark brand of humor, La Tercera dazzles. I was floored by how the novel somersaulted between multiple languages, the personal and the national, overacted tragedy to heartbreaking history, the U.S. and the Philippines.

In Apostol’s latest book, a grieving diasporic daughter tries to make sense of her mother’s life, as well as a mysterious stack of papers that she has inherited—which seems to tell not just the story of her ancestors, but also a kaleidoscopic narrative of Filipino history. La Tercera nestles text within text, making the reader piece together the fragments of history alongside the narrator.

Alongside childhood anecdotes and laughter, Apostol spoke to me over Zoom about the playfulness of (mis)translation, her aversion to linear historical novels, and the question of complicity.

Jaeyeon Yoo: What was the origin point of La Tercera?

Gina Apostol: There seem to be two books in La Tercera, at the very least. So there’s the story of the mother, then there’s the story of the text within the text (within the text!). I foregrounded the mother story, but I had long been writing the background historical story. I liked the historical story, but I needed it to be more charged with something for me. Then, I went home to the Philippines for a book festival. On the plane, I was thinking, “You know, I could really change my novel.” I was already in a type of weird mourning for my mother, because of a comment my sister had made. She said, “You didn’t come home when mommy died.” There was something about going home, and I knew that the story of my mother was somehow related to the work that I was doing. So, I added that pandemic world of grieving. La Tercera became a pandemic novel that became personal, in a way that I actually never do. I don’t consciously put my personal life in my stories. But this one is very conscious; if it was something I could remember, or someone had told me, that seemed to be true—I put it in. I create constraints for myself, in order to get me working; the constraint, in this case, was that it had to be somehow true in some way. I may have remembered wrong, but that’s still my memory.

The novel ended up trying to think through the relationship between that earlier [Filipino] history and my mom’s ideology, her way of being. Almost all of the storytelling is about grief, but it’s also trying to respond to the question of why: Why do people believe these things—believe in the dictator, believe in state corruption? Why is she so attached to the dictator? Why are we so attached to certain kinds of figures and not others? La Tercera became a historical reckoning that was also a personal one.

JY: Along those lines, what does meta-fiction and referentiality do for you, as a writer?

The way we understand our parents is through gaps and holes.

GA: I keep wondering about it myself, to be honest, because it would be much easier to tell the story straight. There might be even more of an impact, if you had a singular dramatic story, like the basic realist storytelling, with limited third, et cetera et cetera. That might be nice. But my problem is, I don’t believe it. I don’t really believe it when I’m doing that story or reading those kinds of stories. So, I’m just going with what makes sense to me, which is that everything that we understand is actually filtered. For me, the referentiality is not about it’s not that kind of postmodern thing. It’s about telling the story in a way that responds to the truth: of how we experience the world, which is through reflexivity and mediation. We’re mediated by our teachers or parents. Obviously, history is hugely mediated, as is power and media—it’s kind of fucked over American history, for instance. And definitely fucked over Philippine history, where we end up honoring our colonizer and forgetting the actual rebel. At the same time, I do believe that, from reflexivity, we can get to a more just way of looking at this history and even a more compassionate way of viewing ourselves.

JY: Given your aversion to “straight” history, I was fascinated by how you laid out this linear idea of “A, B, and C” throughout (the “tercera” form), yet you break it for yourself. Nothing is ever quite completed in this novel; there’s instead an emphasis on the incomplete—the bricolage, the collage, the archipelago. What does the fragment form mean to you?

GA: The fragment form is put together by what I think of as the issue of translation. The coherence of the fragment form is a theory of translation, nationhood, and identity. But on a very simple level, the fragment form is how I learned about this history: through fragments, through fractures, through a sense of “Why was that guy in Indiana in 1903? It doesn’t make any sense!” It’s also because the fragments of my mom’s story, how I heard her life, was very striking to me. The way we understand our parents is through gaps and holes. It’s very hard; we want them to be a fixed thing, but they’re not. Being a child is always like being in a mystery, if you’re thinking about your relationship to your parents! Especially if your worlds are fractured by different political beliefs. So, the fragments have to do with how I came to understand both the national and personal history.

JY: I’d love for you to expand on your point about a theory of translation that glues fragmentation together.

GA: Just my own experience, being Filipino, [means] having multiple languages. I was very clear in the novel that a central language is Waray, the language of the mother. At the same time, you have all these other languages. So you’re constantly in the space of being able to switch from one tongue to the next. If I’m thinking about the fragments of the historical texts (within the novel), the only way you could understand why they’re together would be from the recognition that there are multiple languages within it. You’re just bearing the multiplicity. You’re always confronted with it, you’re always with it. Once you understand that this is a translation, that there is another way to read and there’s another language in there—and there are historical and geographical reasons for the multiple languages—the fragmentation and the sense of confusion actually makes sense.

JY: Right, because confusion is kind of the basic level of being. Translation lets us live with this confusion, I think, without needing it to cohere.

Misreadings are really potent in a colonized history, because the heroes that you love, of course, are the ones actually created by your enemies.

GA: Yes. That ability to sit with it. In terms of colonization, that becomes an interesting thing to bear. Because there’s so much that we’ll be angry and frustrated with—the lack of knowledge and power plays with our sense of identity. But there’s a weird kind of stability once you recognize, “Oh, I don’t understand that. I don’t get it or I misread that.” Because of this condition of translation, you know.

That experience when the narrator can only speak English, not Waray, as a child—I remember being so angry when that happened to me. It was so stupid, I didn’t know my mother’s language. I was truly writing down a list of words, listening, listening, listening [like the narrator]. Then there was that moment: one of the maids and house boys were talking to one another. They were talking about me. They were saying I was a bitch. It was the best. I finally understood Waray. I didn’t put that in the novel, that experience of suddenly understanding, and the great position of being a listener (and they think you don’t understand them).

JY: It’s an incredible feeling, I agree. Whereas the translator is typically regarded as an “invisible” figure, as Lawrence Venuti theorizes, she is made hyper-visible in your novels. What made you foreground the figure of the translator in this way?

GA: Even to understand the plot, you have to see that the translator is there. For me, the act of writing becomes more interesting when I can figure out there’s a manipulation I need to do for the plot. Discover-discover. [A childhood game that the narrator plays in La Tercera.] Everything is discover-discover in the text. The mother. Discover-discover. The papers. Discover-discover. The translator is the ultimate discover-discover, because they own the text.

JY: I was struck by how La Tercera placed translation at forefront, yet, but mistranslation was at its core. Like the slip of the tongue between “rebel” and “rebeal” (reveal); there are misspellings, mishearings.

GA: And there are also misreadings, like the readings that are kind of wrong. That’s not the hero, this is the hero! Misreadings are really potent in a colonized history, because the heroes that you love, of course, are the ones actually created by your enemies.

JY: Connected to mistranslation and “rebel/rebeal,” La Tercera did an incredible job of blurring the line between the rebel and the collaborator. Could you talk more about the relationship between these two, and how they are documented in history?

GA: I’m going to be honest: I am very judgmental. There’s something about me, that’s not even like that will just say, “No, that’s a collaborator. That’s not good.” When you think about history, the ways in which people have to live in that condition of indeterminacy, you don’t know actually what’s going to happen with the revolution that you started. You don’t know actually what it means to side. As a Filipino, I recognize that the history that we’ve been given makes our loyalties so multiple—even from the Marcos years to the revolutionary years. I find collaboration interesting as a writer and, at the same time, I have a sense of compassion for the colonized, which doesn’t happen a lot of times. We tend to judge ourselves for being colonized, but our choices were not necessarily made by us in many ways—it was made through violence, through the hegemonic power of the colonizer, [through] the language of the group that had the guns. I think we need to see that. And if I were going to go with the compassion for the collaborator, it’s good as long as you simultaneously have judgment. It’s hard, with Filipinos. Of course, our heroes are all of the collaborators. They have to be, in order to survive.

JY: Yes, there’s a lot of internal self-tension built in for the colonized. And we don’t live in a world free of collaboration either.

GA: Right, we’re complicit with our late capitalist world. How do you live with that, how do you live in it? At the very least, my novel is trying to open up to that very material condition of complicity.

JY: The complicity question makes me think about your use of mirrors throughout the novel, like the Self-Other complex that you talked about with the mirror neuron syndrome. I’ve never heard of this condition before.

GA: I did that in Insurrecto too, but in a different way, with the double vision. Paul [Nadal] is going to tease me, because he has always said, “Do you know, Gina, there’s always some kind of psychological problem in your books.” This one has the mirror neuron syndrome. There’s something about the organic that I find interesting: the embodied aspect of history. The violence upon the body is being reiterated in whatever psychological condition. In this case, it’s the mirror touch synesthesia problem, when the boy is so engrossed with the other. He can’t separate himself from that other. It’s a problem, and also what happens under the violence of colonization; the violence of that history is that you’re not really clear about why your body responds to whiteness, to Americanness and the Western space. But it’s not actually your fault. The thing about the body is that there’s no blame to it. We tend to blame the victim, but it’s really the structure of imperialism and colonization that is the problem.

JY: Right? We don’t choose what bodies or genetic conditions we’re born into. Genetic here as not just biological DNA, but also the historical genes—inheriting these histories of violence and imperialism.

GA: That’s what I’m trying to say: the truth of violence becomes embodied in the psychological condition.

JY: Psychological conditions, and also hairstyles! At one point, you explicitly talk about how “[War] takes a role on your hair”. There are so many great descriptions of hair in La Tercera, especially as types of language and punctuation marks.

We should remember the people who are fighting for the land, fighting to keep indigenous communities alive. They’re being killed right now.

GA: You know why? The Filipino postcards of women from the ’70s, they’re just amazing. The bouffants of the women are crazy; they’re like commas. I don’t know how they do it, but I really appreciate it. I mean, it’s the problem that the Filipinos have, they really love that era. They still do. They love the glamor—and can I blame them for it? No. I mean, I can. It’s a desire, but I can also reflect back how that desire has been harmful.

For a very long time, I was angry with my mother for loving [Fernando, the dictator], but, at the same time, it makes sense to them. This was a beautiful figure who was theirs, who gave them a sense of power and representation that was really, really damaging. [This type of] simultaneity is constant. I grew up with it. My experience of Filipino culture and history is that it is simultaneous. They’re both crying over something and then it becomes a parody of whatever it is that they’re doing. If you go to a funeral, it’s really tragic—and then they’re playing mahjong at the same time and overacting! OA! It’s everywhere!

JY: We keep coming back to this idea of holding “doubleness” (Self-Other) or simultaneity. Both things are true: you’re genuinely sad and performing the sadness at the same time. I think La Tercera is so good at questioning this binary we’ve set up between the “true” and “false,” “authentic” and “fake.”

GA: Questioning it, yes, and always recognizing what you have to figure out: when you are being manipulated and being violated. You know, it could be both—you can be violated by the authentic.

JY: Any last thoughts you’d like to share with your readers?

GA: One thing I was trying to work out [with La Tercera] was that it takes us Filipinos a very long time to figure out who to remember in history. I think that’s sad, especially with the violent history that is present in the Philippines now, there are all these people being killed. What we remember is the name of the Marcoses. We should remember the people who are fighting for the land, fighting to keep indigenous communities alive. They’re being killed right now. That concept of how we remember, and trying to remember better. I actually have cousins, and when I ask them, “Hey, your Lolo was a revolutionary, can you tell me any stories?” They have no stories. He is prominent in the histories I was reading about Leyte. I didn’t know about him and definitely wasn’t taught in school, but even his family didn’t know. That’s the power of genocide, that type of forgetting. It was so violent that you were not allowed to remember. Forgetting is an aspect of genocide. For an American audience, this novel is also their history. They are a part—if I’m going to talk about the complicity and collaboration of the Filipinos, what about the complicity of the Americans in this history they don’t even know?