Greys and whites split the sea,

mottled flecks of cream

that simmer in the surf,

hinting at the beasts

that lurk beneath.

Metallic vessels tower overhead,

global fleets of freight and load

that cut through filtered lanes

with wanton ease,

striking their unheeded prey

with hidden blows

of pride,

and gall,

and steel.

A clumsy chant to

stiff remains

that fall to the floor

without a sound.

This poem is inspired by recent research, which has found that shipping poses a significant threat to the endangered whale shark.

The whale shark is the largest fish in the world, growing to somewhere between 18 and 20m in length, and weighing up to 10 thousand kg. They are found in warm seas throughout the world and are a docile species that feeds on plankton and other tiny sea creatures. Whale sharks play an important role in the health of our oceans, by regulating plankton levels, and preventing these microscopic organisms from growing without restriction. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has declared the species endangered, and whilst international trade in whale shark meat, fins, and other products has been regulated since 2003, there continues to be a decline in whale shark numbers that cannot be explained by fishing or other related impacts alone. As whale sharks spend a large amount of time in surface waters and gather in coastal regions, one theory is that collisions with ships might be causing a substantial number of whale shark deaths.

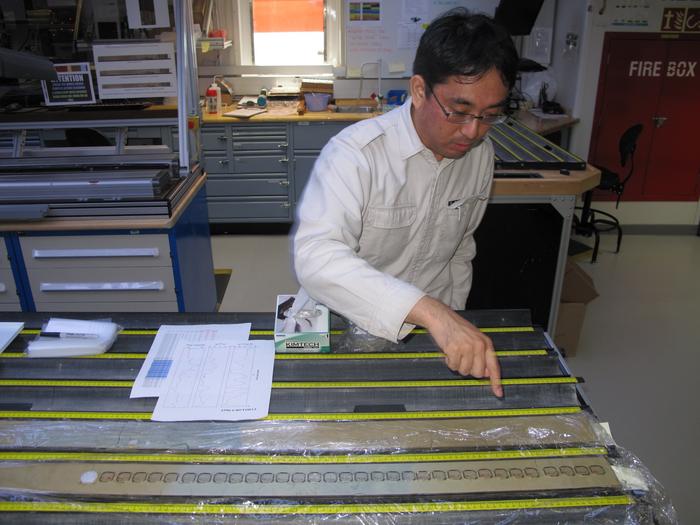

In this new study, researchers used satellites to track the movements of nearly 350 tagged whale sharks across the globe, alongside shipping vessel activity to identify areas of risk and possible collisions. These observations revealed whale shark hotspots which overlapped with global fleets of cargo, tanker, passenger, and fishing vessels, i.e. the types of large ships that are capable of striking and killing a whale shark. In fact, over 90% of whale shark movements fell under the footprint of shipping activity. The researchers also found that whale shark tag transmissions were ending more often in busy shipping lanes than expected, with the loss of transmission likely due to whale sharks being struck and killed by ships, before sinking to the ocean floor. At present there are no international regulations to protect whale sharks against ship collisions. However, it is hoped that the findings from this study can be used to inform future management decisions and protect whale sharks from further population declines.