People have long stoked an urban-versus-rural rivalry, with vastly different cultures and surroundings. But a burgeoning movement—with accompanying field of science—is eroding this divide, bringing more of the country into the city. It’s called rurbanization, and it promises to provide more locally grown food, beautify the built environment, and even reduce temperatures during heat waves.

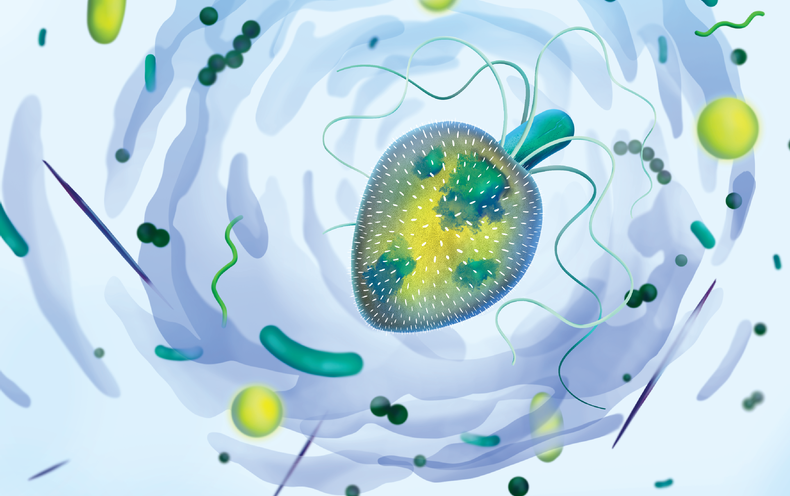

It’s also reversing the longstanding assumption that growing food is straight-up bad for biodiversity because clearing land for agriculture necessitates removing native plants and animals. Ecologist Shalene Jha of the University of Texas, Austin says this idea was based on observations of rural agriculture, where growing industrialized swaths of corn or wheat can be catastrophic for existing ecosystems. But that doesn’t hold for the urban farms, gardens, and even smaller green spaces.

In a recent paper in the journal Ecology Letters, Jha and her colleagues showed that urban gardens can actually boost biodiversity—particularly if residents prioritize planting native species, which attract native insects like bees. “The gardener actually has a lot of power in this scenario,” says Jha. “It doesn’t matter how large or small the garden is. It’s the practice of cultivating the landscape—and the decisions they make about the vegetation and the ground cover—that ultimately decide the plant and animal biodiversity there.”

Jha’s team characterized the biodiversity of 28 California urban gardens over the course of five years. Far from the mono-cropped monotony of a wheat field, they found rich ecosystems humming with activity that, in turn, increased species diversity. The researchers found predators like birds and ladybugs, which prey on crop-munching insects and thus help increase yields, and an abundance of pollinators like bees, which also benefit from crop diversity and increase plant productivity. That means urban gardens aren’t just producing food for people, but for other species as well. “They’re actually supporting incredibly high levels of plant and animal biodiversity,” Jha says.

This biodiversity is largely due to a strategic trade-off. One of the challenges of urban gardening is that it requires intensive manual labor: You can’t drive a combine through a city at harvest time. But that limitation turns out to be an ecological blessing. Because everything is done by hand, urban farmers can grow all sorts of plants right next to each other, packed in tightly to increase yields.

In another study published this month in the journal Agronomy for Sustainable Development, a separate team of researchers looked at 72 urban agriculture sites in France, Germany, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. “We see pretty diverse growing spaces that often are growing a huge variety of crops, as well as non-food products,” says study author Jason Hawes, an environmental sustainability researcher at the University of Michigan. On average, the sites grew 20 different crops. “Lots of folks were also just growing flowers for fun in their visual gardens, and the community gardens have flowers planted to make the space more pleasant,” he says. “These sorts of things do contribute to local biodiversity.”