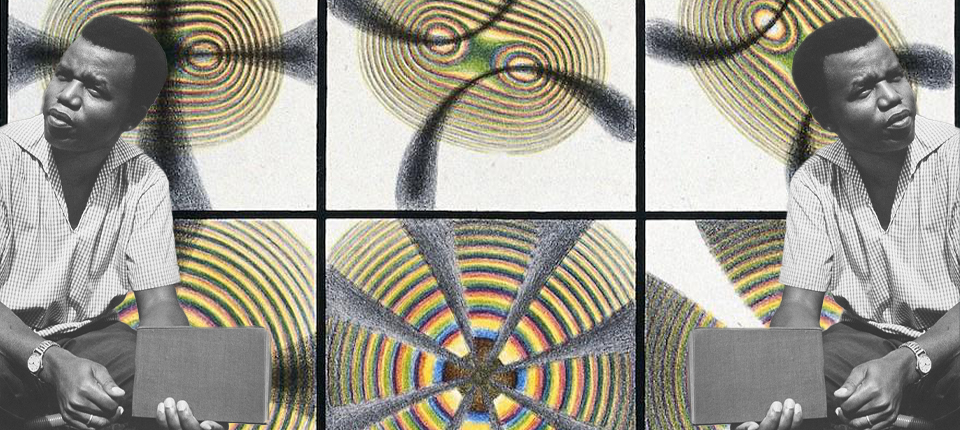

While the whole blood transcriptomics was helpful, it only provided a general picture of what was going on. Next, the scientists turned to a technique called CITE-seq. This allowed them to find out which cells were expressing which genes differently across males and females, and what specific proteins they were creating. The best part was that CITE-seq could be used with the same blood samples collected from the patients. “There’s only one type of sample, and you just measure the hell out of it,” Tsang says.

A particular type of cell seemed to be contributing to the response to the flu vaccine: effective-memory T cells (which are generated after an infection and can “remember” the specific pathogen they encountered) with a receptor called GPR56 expressed on their surface. As it turns out, Covid-recovered males had more of these cells compared to Covid-recovered females and healthy controls. But why would these cells, seemingly linked to Covid, respond to a flu vaccine?

“The canonical assumption is that an infection will generate cells that are specific to the virus,” Tsang says. But as he explains, this isn’t necessarily the case. Other more broadly reactive immune cells can be activated too. Known as “bystander cells,” these react very quickly to vaccination, sending up alarm bells that lead to the immune system creating antibodies in response.

Indeed, when the scientists examined the GPR56-positive T cells, they found that they shared similarities with bystander cells already known to be activated during acute Covid infection. Therefore, they hypothesized, these GPR56-positive cells probably acted in a way similar to bystander cells, persisting in the body after Covid, and kick-starting immune responses to other invaders—in this case, the flu vaccine.

To prove this theory, the scientists needed to see how GPR56-positive T cells responded to something akin to infection or vaccination. When they isolated these T cells, cultured them in a petri dish, and stimulated them with small signaling molecules called cytokines known to be produced during infection or vaccination, the scientists found that the T cells secreted high levels of inflammatory proteins that had been found in the Covid-recovered males—providing evidence that this cell type could indeed have triggered the immune response that ultimately created more flu antibodies. They had found their smoking gun.

Consiglio is curious to see, in the future, what effect these immune system differences between Covid-recovered males and females have when a person is actually infected by the flu or another virus. Looking at sex and prior infections also raises the question of how other factors might influence the immune response. Sabra Klein, a microbiologist at Johns Hopkins University, is interested in seeing how something like age might also factor into the equation and perhaps create a sliding scale of immune responses. “We often treat these kinds of variables as binary—you’re young or you’re old, you’re male or you’re female—and we often don’t do enough to interrogate these intersections,” Klein says.

Ultimately, Tsang and his team hope that these results can help scientists design more effective vaccines or figure out ways to predict how a person might respond to an infection. They want to find out if those GPR-positive cells can be more efficiently primed to respond to a pathogen. On the flip side, the scientists are also curious about how these cells (and others) function during autoimmunity, where the immune system is overactive.

Until then, they will continue to appreciate the complexities of the immune system—particularly how it has evolved during the pandemic. “We always thought of looking at the human immune system as a very diverse natural experiment,” Tsang says. Thanks to the pandemic, the opportunity to learn from this experiment was that much greater—meaning we now know more about why our immune systems are so different, and how they change over time.

.jpg)