Kenward Elmslie was an award-winning poet, lyricist, literary magazine editor, and opera librettist whose work thrived in collaboration with other writers, musicians, and visual artists. Elmslie, who was a grandson of Joseph Pulitzer, died at age 93 in June 2022. Elmslie met Lucia Berlin when they were both in Boulder, Colorado, teaching at Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program in 1994, and they became fast friends.

At the time, Berlin was an accomplished but little read short story writer. In their correspondence, while Elmslie reports his own good reviews (and some bad), Lucia mostly recounts shocked reactions of neighbor ladies who are scandalized by the content of her stories. Still, Elmslie believed in Berlin. He wrote about Where I Live Now, Berlin’s 1998 volume of selected stories, “The placement of the tales is, I think, masterful. Your Body of Work, by now, is so strong. Who else has a continuum of short fictions that hold up like—like Gang Busters—as my Tejan collaborator-composer Claibe [Richardson] would say. Your very own niche. In ancient times, Kathy Mansfield. Dotty Parker. And Tru [Capote].”

At the time, Berlin was an accomplished but little read short story writer. In their correspondence, while Elmslie reports his own good reviews (and some bad), Lucia mostly recounts shocked reactions of neighbor ladies who are scandalized by the content of her stories. Still, Elmslie believed in Berlin. He wrote about Where I Live Now, Berlin’s 1998 volume of selected stories, “The placement of the tales is, I think, masterful. Your Body of Work, by now, is so strong. Who else has a continuum of short fictions that hold up like—like Gang Busters—as my Tejan collaborator-composer Claibe [Richardson] would say. Your very own niche. In ancient times, Kathy Mansfield. Dotty Parker. And Tru [Capote].”

Kenward’s correspondence, friendship, and financial support that he helped arrange through arts funding organizations sustained Berlin until her death in 2004. In turn, Berlin recommended one of her favorite students, Chip Livingston, to become Elmslie’s assistant when it was clear his other assistants were taking advantage of his resources.

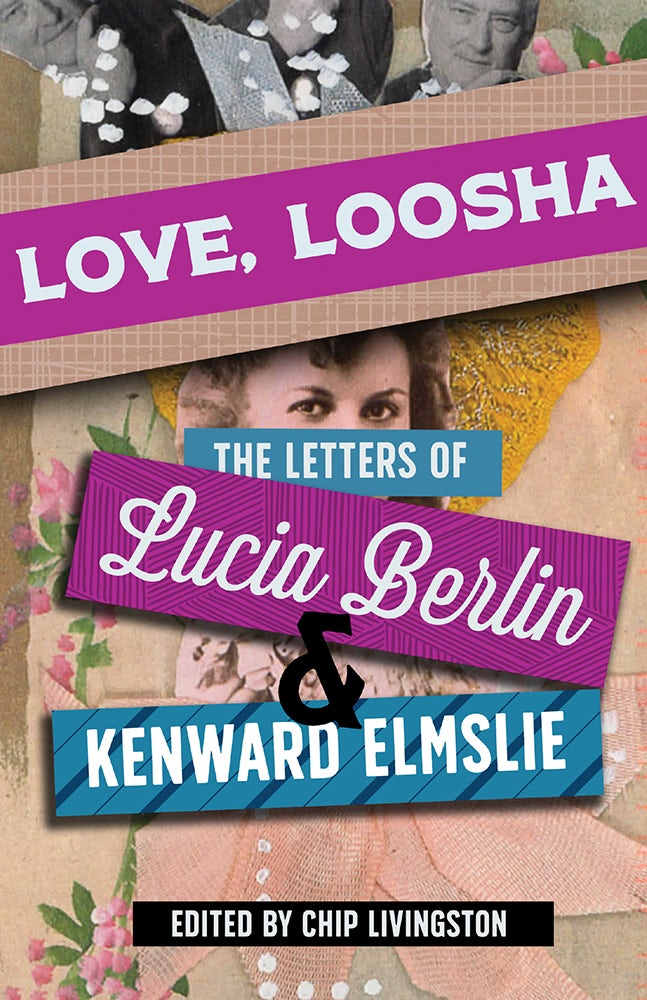

Livingston is a professor of creative writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts and has published five books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, including Owls Don’t Have to Mean Death and Naming Ceremony: Stories. Livingston served as Elmslie’s personal assistant for 10 years, and edited a volume of Berlin and Elmslie’s letters that they both fervently wished to see in print, Love, Loosha: The Letters of Lucia Berlin and Kenward Elmslie. I met Chip when we were students of Berlin’s at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Love, Loosha brought Lucia back to me, as the rare, insightful, observant, funny, and erudite artist I knew her to be.

Jenny Shank: My first few questions are logistical. How did you gather and arrange these letters? Lucia writes that she attempted to organize them herself, but she couldn’t manage it: “I started to tackle the Elmslie Letters. HUGE TASK. There are big envelopes, boxes, files, bags, folders bulging with letters. Many many so far have no legible post office date nor date written by you inside. How could I have such a massive mess?” Did you have any help from the University of California, San Diego, which holds Kenward’s papers? Has any institution collected Lucia’s papers?

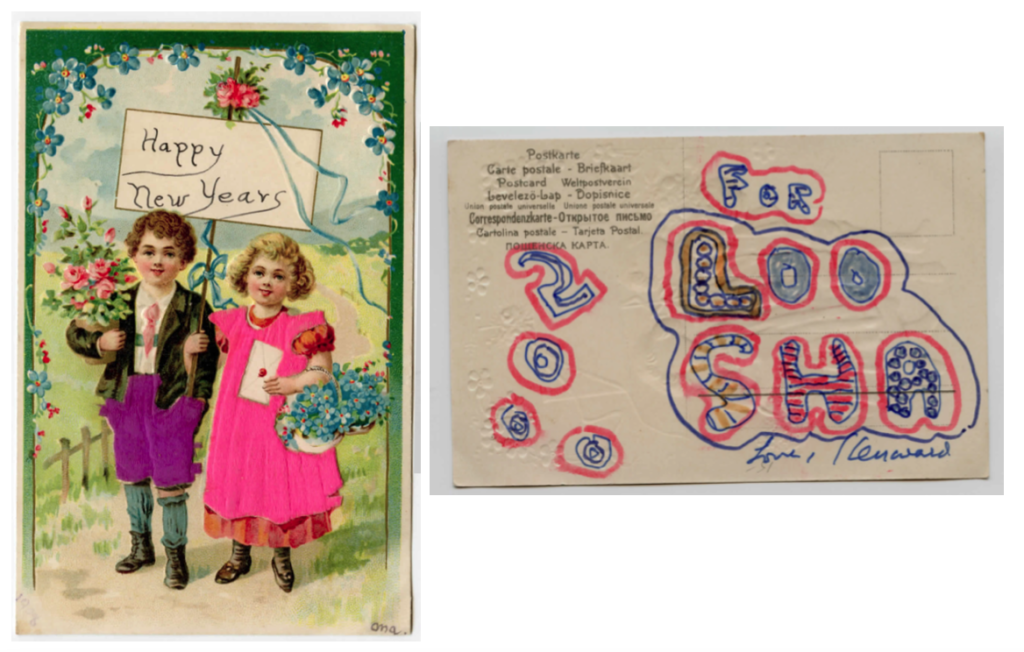

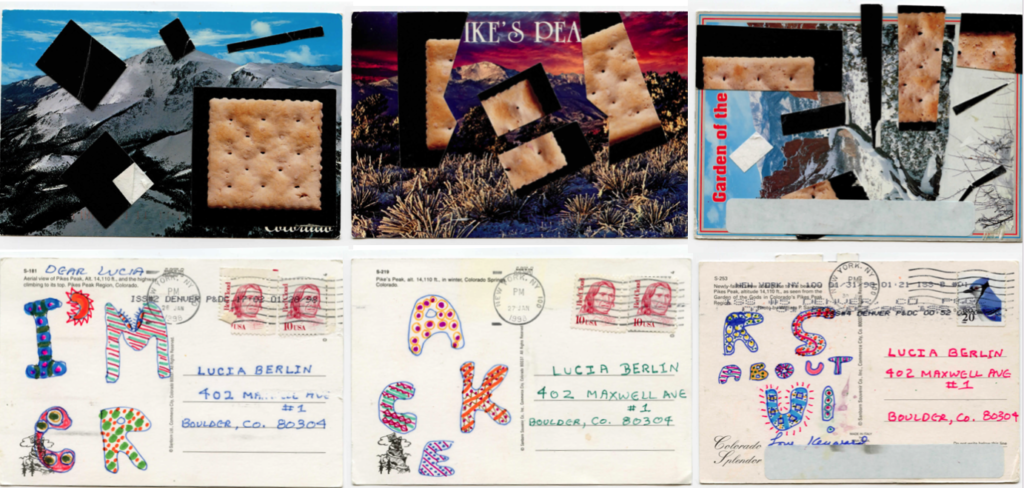

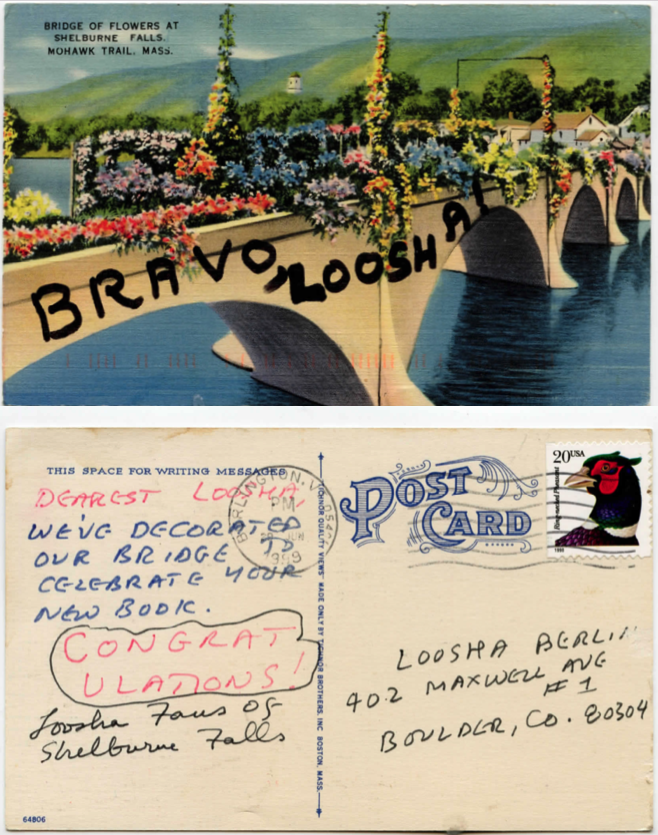

Chip Livingston: It was an enormous project. There were more than a thousand pages of letters and postcards between Lucia and Kenward to go through and choose from. And while UCSD and Harvard University (which purchased Lucia’s collected archives) do house the original letters now, I was using copies as scanned by Lucia’s son, Jeff Berlin, as well as those scanned by the poet Ron Padgett, who oversees the Kenward Elmslie Irrevocable Trust. Jeff and Ron sent the letter scans to me before sending the originals to the university archives, and I then went through the pages one by one to date letters by context (if they didn’t have written dates), to sequence them, to transcribe Lucia’s many handwritten letters, and finally to select which letters made most sense to include in the final manuscript, which is about 40 percent of the actual collected correspondence between them. Jeff Berlin and Ron Padgett were essential to the project, as were Lucia’s and Kenward’s own habits to save and safeguard the letters. At Lucia’s memorial service in 2004, her sons brought a bag full of letters that Kenward had sent Lucia over the years, and I returned them to Kenward to add to his collection of her letters in New York.

JS: Apart from the logistics, was putting this book together difficult work, emotionally? As I was reading it, I was caught up in my own emotions so many times—wishing I’d written more to Lucia during those stretches when she writes about being lonely, wishing I could tell her how everyone appreciates her work now, wishing I could just chat with her about whatever she was talking about in a particular letter. For you, who knew and loved both these people, I imagine the project must have tugged at your heart constantly. How did you manage that?

CL: It was certainly an emotional project for me, and like you, as I read the letters from Lucia I heard her voice, and I returned to letters and emails that she’d sent to me as well. I even dreamed I was still getting emails from her about the project, would wake up disappointed not to see a note from her in my inbox. Being equally close to Kenward, and reading about times he narrated for Lucia that I was a part of, brought more bittersweet memories of all three of us. By the time I was actively working on the project, Kenward’s health had deteriorated to the point that he was no longer speaking, but I’d video call Kenward through his assistant and tell him about how the book was coming along. Kenward’s eyes would light up, he’d focus on my face and voice. Then when Kenward died in June of this year, as I was finalizing page proofs for Love, Loosha, and knowing Kenward would never see the actual book in person, it brought up another kind of grief for my losses of both of them.

JS: Lucia reiterates several times that she believes Kenward’s letters are so fabulous that they need to be published, though he doesn’t really respond. On a few occasions he did publish or perform reworked portions of the letters. But you finally brought their vision to fruition. Was this collection something you always wanted to do, knowing how much they desired it? Once Lucia achieved posthumous fame, did you realize there might be an audience for these letters?

CL: Lucia often suggested that Kenward’s letters should be published, she found them thrilling works of art, not just the visual collaging he added to them, but for their “undercurrent of Stage THRILL” and their “example of how a great artist sees the world.” Kenward said maybe there could be a combined correspondence published someday, but like Lucia, he thought the task to organize them was overwhelming and he never acted on it. Even though they both shared the other’s letters with me, and I was often the deliverer of letters and messages between Kenward and Lucia, it never occurred to me that I might try to take on the project myself, until 2018 when Lucia’s unfinished memoir and selected letters was published. When I read Lucia’s letters to her mentor, friend, and poet Ed Dorn in Welcome Home, all written between 1959 and 1965, I realized how much more self-confident she’d become by the time she began writing regularly to Kenward in 1994, and how much more self-realized Lucia was later in her life, and I hoped to possibly reflect that in a collection of her correspondence with Kenward. I approached Jeff Berlin and Ron Padgett with the idea, they approved, and then we began collecting and scanning the letters, organizing them, and putting together the book proposal and final manuscript for University of New Mexico Press.

CL: Lucia often suggested that Kenward’s letters should be published, she found them thrilling works of art, not just the visual collaging he added to them, but for their “undercurrent of Stage THRILL” and their “example of how a great artist sees the world.” Kenward said maybe there could be a combined correspondence published someday, but like Lucia, he thought the task to organize them was overwhelming and he never acted on it. Even though they both shared the other’s letters with me, and I was often the deliverer of letters and messages between Kenward and Lucia, it never occurred to me that I might try to take on the project myself, until 2018 when Lucia’s unfinished memoir and selected letters was published. When I read Lucia’s letters to her mentor, friend, and poet Ed Dorn in Welcome Home, all written between 1959 and 1965, I realized how much more self-confident she’d become by the time she began writing regularly to Kenward in 1994, and how much more self-realized Lucia was later in her life, and I hoped to possibly reflect that in a collection of her correspondence with Kenward. I approached Jeff Berlin and Ron Padgett with the idea, they approved, and then we began collecting and scanning the letters, organizing them, and putting together the book proposal and final manuscript for University of New Mexico Press.

JS: The quality that strikes me most about these two artists and friends is their playfulness and creativity. They love playing with language and joking. This collection captures an aspect of Lucia’s voice that I don’t think is always spoken about when her stories are discussed—she was so funny! (Like that story about when she had to go get new tires for her wheelchair, and she ends up at this wacky place, and when the repairman appears she thinks, “Oh my god this is all a front for some huge methamphetamine laboratory.”) Are there aspects of Kenward and Lucia’s work or just ways of being that you think have been overlooked that you hope this collection brings to light?

CL: Yes, Lucia was so funny in the letters, and while she often was silly with me too, especially playing around with words and perspectives, how many actual jokes she shared with Kenward in her letters surprised me. There were many more jokes she told that aren’t in the final book, but like you, how pervasive Lucia’s humor is in the letters was one of the bigger revelations to me as I read through all the collected correspondence. Kenward’s poetry and lyrics are also full of language twists and lingo gymnastics, and having lived with him for ten years, I was much more familiar with his particular brand of wackiness and humor.

JS: I think I’m referred to, obliquely, in one letter, dated from the time I was in Lucia’s fiction workshop. She writes, about her students, “They take notes. (On ad-lib insanities that occur to me). A few Wonderful Born Writers, a few god-awful students.” I was the note taker. I wrote down the funny one-liners and insights Lucia said during the semester, along with jokes my classmates told, and at the end of the semester I printed them out and shared them. I think she thought her quotes were silly, but that’s what I loved about them. There’s such depth to her silliness, which is what is captured in the letters. Kenward loved to engage in silly wordplay too. Do you think that being silly together was an important part of their friendship?

CL: I think being silly together, joking as much as they did, was a balance to the depth of their honesty and their vulnerability they shared with each other. Kenward wrote of being nicknamed “Homo” in boarding school, of being taken advantage of by previous “helpers,” of the pain of losing friends and lovers to AIDS, and of writing about those losses in poetry and song. Lucia wrote of her oldest son’s addiction and homelessness, the painful additional truths behind some of her stories where she’d felt “the actuality just doesn’t disappear into the writing.” I think part of the reason they could be both silly and so vulnerable with each other is because they completely trusted the other wasn’t going to judge them in return.

JS: I was struck by what good taste Lucia and Kenward had. Many people and works that they praised turned out, in the past two decades, to have been redeemed or further recognized for their excellence. For example, Lucia is sympathetic toward Monica Lewinsky right from the start. She is riveted by young Serena Williams. She appreciates the critic Hilton Als, the work of Aleksandar Hemon, and the films of David Lynch and Pedro Almodovar. Did they have a sense that they knew what good art was, despite whatever was popular at the time, and they were going to keep on making it?

CL: Kenward and Lucia had a special sense of recognizing depth in narrative detail, dedication in art, and commitment in people. I don’t think Lucia or Kenward considered “the public” or “publication” when they were writing… at least not in terms of mass market numbers. Their commitment to writing was to the writing.

JS: In the last letter Lucia wrote, about a month before she died, she sounded like she was looking forward to writing again, and I loved that she was so funny and loving to Kenward in it (“I wish I had been a gay man and one of your lovers.”) and she ended on those jokes that she handwrote in because there was blank paper left at the end. What did you learn from going on this journey through the letters in this book? Does it make you want to go find a literary penpal?

CL: I learned from their letters how much opportunity for “story” they found in the mundane, in observation of others, of asking themselves who people were and what were their stories, what were their secrets. I learn a lot about how Lucia constructed her short stories in the questions and fantasies she created around witnessed encounters, how Kenward created characters from postcard vendors and handymen: they both saw potential in the everyday, and I think having both had their own life secrets (Kenward’s homosexuality in boarding school, Lucia’s alcoholism) that they suspected everyone they met had a secret story one could invent or discover.

I really miss my correspondence with Lucia. We wrote each other frequently, and I haven’t had a true pen pal since she passed. I know several contemporary writers who have ongoing letter exchanges. I’d love a literary pen pal, but who takes the time, and who has the time? I live in Uruguay and the mail still takes three months to arrive in or from the United States. I think my social media connections with other writers provide a sense of what the “posted letter” once offered. But I love letters, love literary letters, and love how letters and other epistolary forms enter literature and broadcast media in important plot-informing ways. I learned so much from both Lucia and Kenward, in person and in their letters. I’m so grateful to them both, and I’m so grateful to have edited this book of their letters.