This story originally appeared on High Country News and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

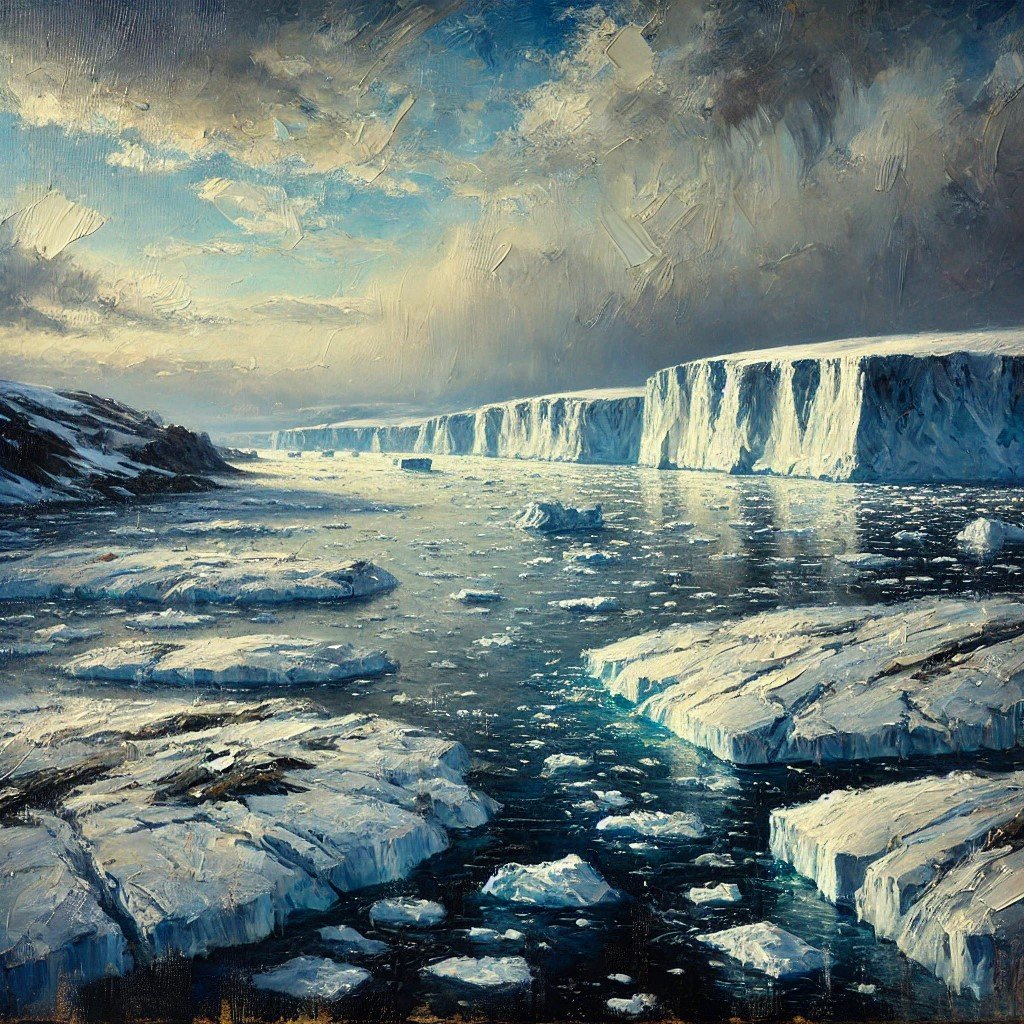

Dozens of once crystal-clear streams and rivers in Arctic Alaska are now running bright orange and cloudy, and in some cases they are becoming more acidic. This otherwise undeveloped landscape now looks as if an industrial mine has been in operation for decades, and scientists want to know why.

Roman Dial, a professor of biology and mathematics at Alaska Pacific University, first noticed the stark water-quality changes while doing field work in the Brooks Range in 2020. He spent a month with a team of six graduate students, and they could not find adequate drinking water. “There’s so many streams that are not just stained, they’re so acidic that they curdle your powdered milk,” he said. In others, the water was clear, “but you couldn’t drink it because it had a really weird mineral taste and tang.”

Dial, who has spent the last 40 years exploring the Arctic, was gathering data on climate-change-driven changes in Alaska’s tree line for a project that also includes work from ecologists Patrick Sullivan, director of the Environment and Natural Resources Institute at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and Becky Hewitt, an environmental studies professor at Amherst College. Now the team is digging into the water-quality mystery. “I feel like I’m a grad student all over again in a lab that I don’t know anything about, and I’m fascinated by it,” Dial said.

Most of the rusting waterways are located within some of Alaska’s most remote protected lands: the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, the Kobuk Valley National Park, and the Selawik Wildlife Refuge.

The phenomenon is visually striking. “It seems like something’s been broken open or something’s been exposed in a way that has never been exposed before,” Dial said. “All the hardrock geologists who look at these pictures, they’re like, ‘Oh, that looks like acid mine waste.’” But it’s not mine waste. According to the researchers, the rusty coating on rocks and streambanks is coming from the land itself.

The prevailing hypothesis is that climate warming is causing underlying permafrost to degrade. That releases sediments rich in iron, and when those sediments hit running water and open air, they oxidize and turn a deep rusty orange color. The oxidation of minerals in the soil may also be making the water more acidic. The research team is still early in the process of identifying the cause in order to better explain the consequences. “I think the pH issue”—the acidity of the water—“is truly alarming,” said Hewitt. While pH regulates many biotic and chemical processes in streams and rivers, the exact impacts on the intricate food webs that exist in these waterways are unknown. From fish to stream bed bugs and plant communities, the research team is unsure what changes may result.

The rusting of Alaska’s rivers will also likely have an impact on human communities. Rivers like the Kobuk and the Wulik, where rusting has been observed, also serve as drinking water sources for many predominantly Alaska Native communities in Northwest Alaska. One major concern, said Sullivan, is how the water quality, if it continues to deteriorate, may affect the species that serve as a main source of food for Alaska Native residents who live a subsistence lifestyle.

![‘911 Lone Star’ Season 5 Episode 8: Tommy’s Cancer Setback [VIDEO] ‘911 Lone Star’ Season 5 Episode 8: Tommy’s Cancer Setback [VIDEO]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/911-lone-star-season-5-episode-8-tommy-cancer.jpg?w=650)

.jpg)