Rian Johnson’s highly anticipated sequel to his whodunit Knives Out, entitled Glass Onion, has been praised by critics for a style that’s just as subversive as its predecessor and devilishly complex plotting to match. Like the first movie, Glass Onion showcases some of its most crucial scenes from more than one perspective, giving the audience a rounded portrait of major story incidents.

While it may be the latest film to utilize “the Rashomon effect,” Glass Onion is hardly the first. Akira Kurosawa pioneered this cinematic technique with his revolutionary masterpiece Rashomon and it’s since been adopted by Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

10/10 Knives Out (2019)

With the twisty plotting of Knives Out, Rian Johnson singlehandedly revitalized the whodunit genre. The movie begins with the murder of mystery author Harlan Thrombey, as seen from the perspective of his nurse Marta Cabrera. As the movie goes on and discerning, debonair detective Benoit Blanc takes on the case, Johnson fills in the missing pieces of the puzzle.

By the time Blanc makes his accusation, the audience has a whole new understanding of the night in question than they had after seeing it from Marta’s point-of-view in the opening sequence.

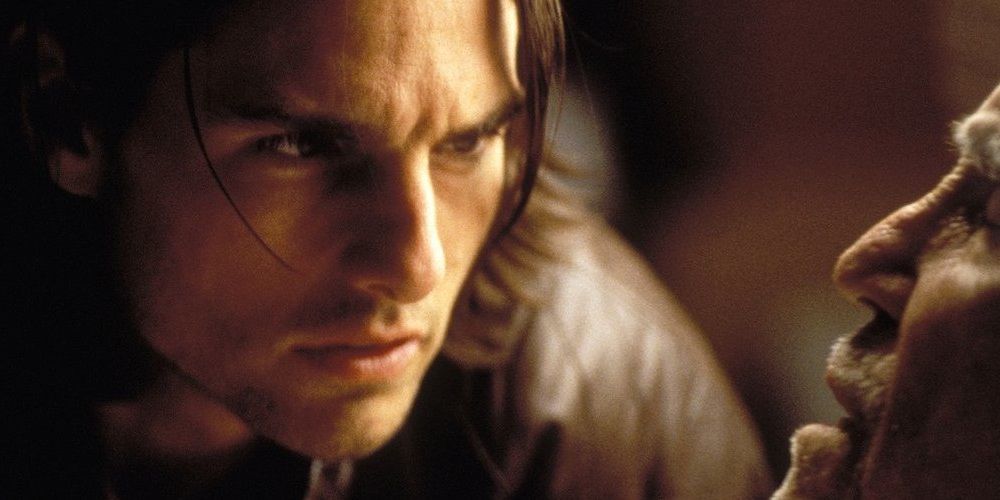

9/10 The Last Duel (2021)

Ridley Scott returned to the historical epic genre to tell the timely tale of the last officially sanctioned duel in French history. The Last Duel adopts the classic Rashomon style to tell the same story from three perspectives: a noblewoman who is assaulted in her home; her husband, a respected knight; and her attacker, a squire.

Every perspective is introduced with a caption: “The truth according to…” Poignantly, when the movie gets to Marguerite’s perspective, the words “according to Marguerite de Carrouges” disappear, leaving behind just “the truth.”

8/10 Snake Eyes (1998)

Brian De Palma’s cult classic Snake Eyes stars Nicolas Cage as a crooked cop who finds himself at the center of a murder conspiracy during a high-profile boxing match. As with any De Palma film, Snake Eyes oozes style, but this one is more Kurosawa than Hitchcock.

The complex storytelling of Snake Eyes was a point of negative criticism for contemporary reviewers, but the film is now revered for eschewing the usual action movie formula to jump between the characters’ perspectives.

7/10 Magnolia (1999)

Paul Thomas Anderson took his own crack at the “hyperlink cinema” style perfected by Robert Altman with his own sprawling ensemble piece, Magnolia. While Magnolia’s bloated runtime and preachy messaging prevented it from topping Boogie Nights as Anderson’s magnum opus, its use of character perspectives is fascinating.

In an early sequence, a suicidal man jumping off a rooftop is intercut with an accidental gunshot firing through a window he passes on his way down.

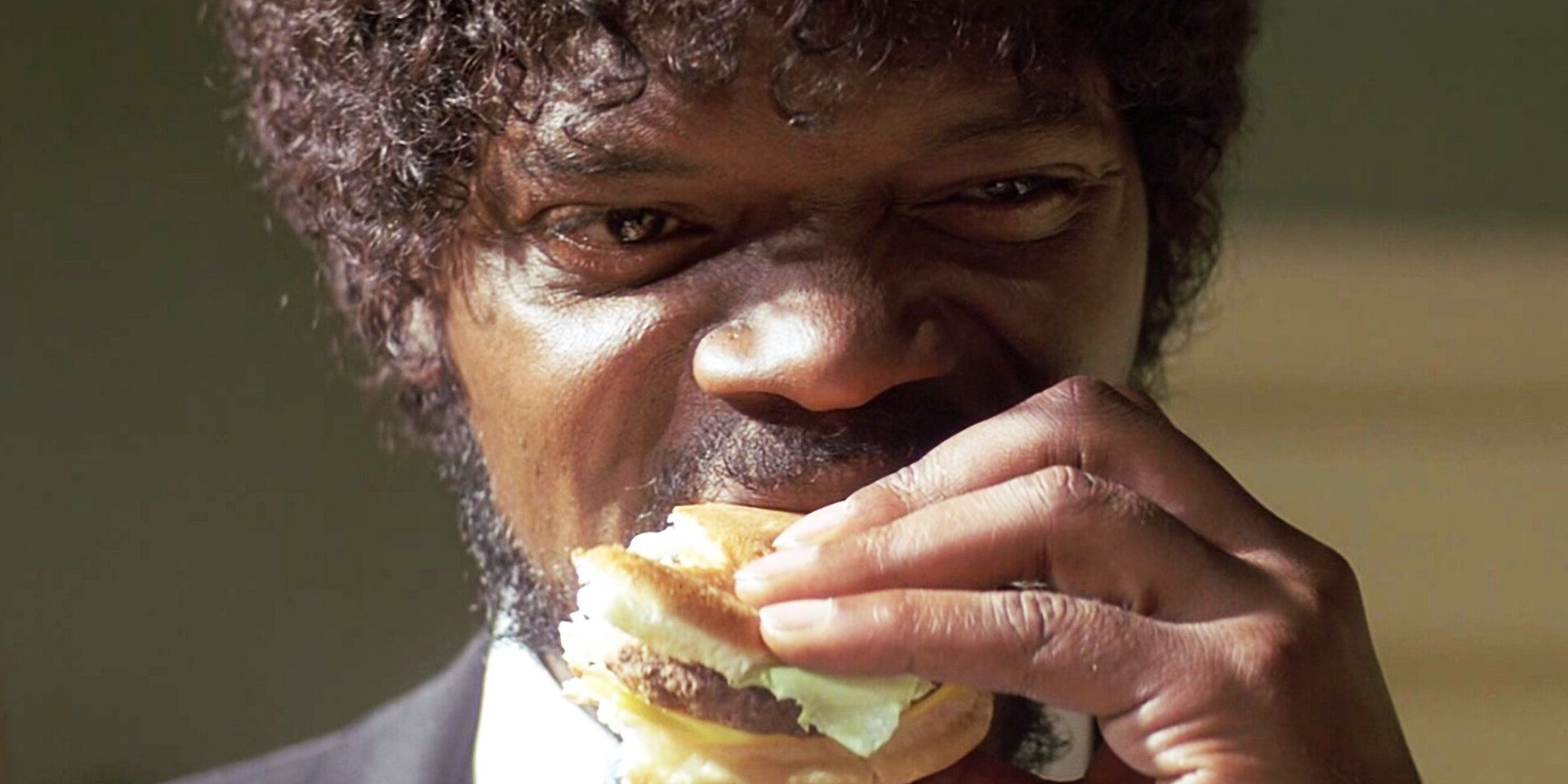

6/10 Pulp Fiction (1994)

Unlike many filmmakers struck by “second album syndrome,” Quentin Tarantino’s second movie lived up to his first. Pulp Fiction took Reservoir Dogs’ nonlinear storytelling and cross-cutting to another level with a crime anthology whose stories all intertwine with one another. For example, the Bonnie and Clyde-esque diner robbers in the opening scene come back around in the finale when the gun-toting hitmen are revealed to be enjoying a nutritious breakfast in that very diner.

Depending on the characters’ perspective of a given scene, Tarantino changes little details like the phrasing of dialogue. This ties into the theme of unreliable witnesses that forms the backbone of this visual narrative style.

5/10 Amores Perros (2000)

Alejandro González Iñárritu scored one heck of a directorial debut with his beautifully realized triptych Amores Perros. The film, which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, takes three separate perspectives of the same car crash in Mexico City.

The story follows a dogfighting teenager, an injured model, and a sinister assassin who would’ve never come into contact with each other if it hadn’t been for the crash.

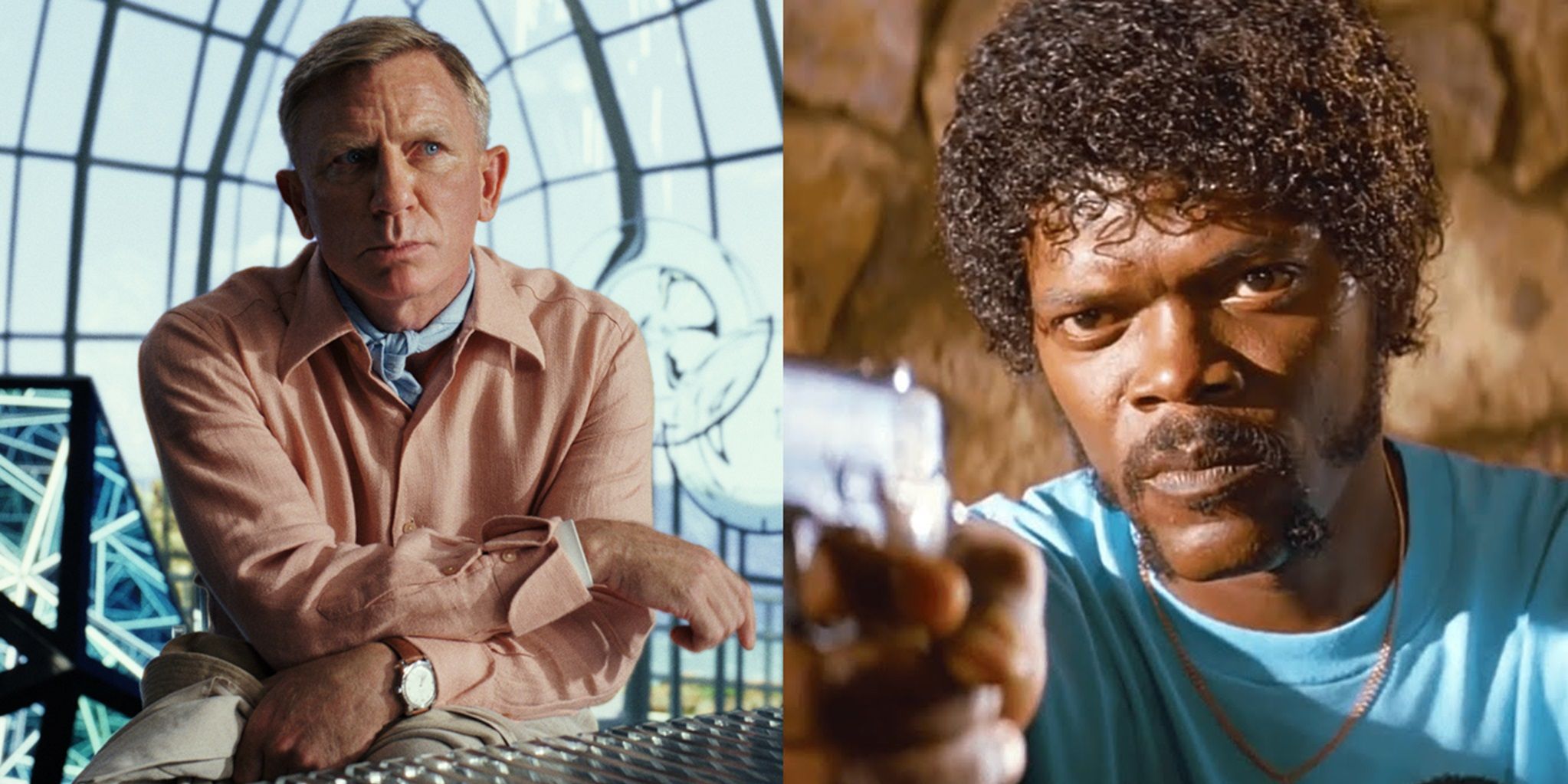

4/10 Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Rian Johnson has continued the Knives Out franchise tradition of exploring different characters’ perspectives with the convoluted visual language of Glass Onion. The standalone sequel finds Blanc working a new case, trying to get to the bottom of another murder during a tech billionaire’s island getaway.

From flashbacks to recontextualized scenes from different characters’ points of view, Glass Onion once again deploys all the tricks and techniques that made the first Knives Out movie so engaging – and uses them masterfully.

3/10 The Killing (1956)

Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing is both a quintessential heist movie and a subversion of the formula. It starts with the traditional setup of a career criminal assembling a crew for one last job, but it takes a complicated turn when one of the thieves tells his wife about the job and she hatches a scheme of her own.

With its thrilling crime story told from several different perspectives, The Killing is one of Kubrick’s most rewatchable movies – there’s a lot to unpack on repeat viewings.

2/10 Jackie Brown (1997)

After solidifying his reputation as one of the greatest living filmmakers with Pulp Fiction, Tarantino followed it up with his first (and, so far, only) adaptation, Jackie Brown. Based on Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch, Jackie Brown once again shifts between different characters’ perspectives. Tarantino uses a split-screen effect to show everyone’s perspective of the climactic heist.

Being beholden to existing source material gave Jackie Brown a kind of discipline that isn’t usually seen in Tarantino’s work. Thanks to Tarantino’s uncharacteristic restraint and Pam Grier and Robert Forster’s palpable chemistry, Jackie Brown still holds up today as a masterfully crafted crime thriller.

1/10 Rashomon (1950)

One of the many ways that Akira Kurosawa revolutionized the film medium was by inventing and perfecting the “multiple perspectives” style with his 1950 masterpiece Rashomon. Four characters each give their own account of a samurai’s murder, telling the same story in vastly different ways.

After Kurosawa’s definitive depiction of the unreliability of eyewitness accounts captured it so perfectly, Rashomon became the namesake of this phenomenon.