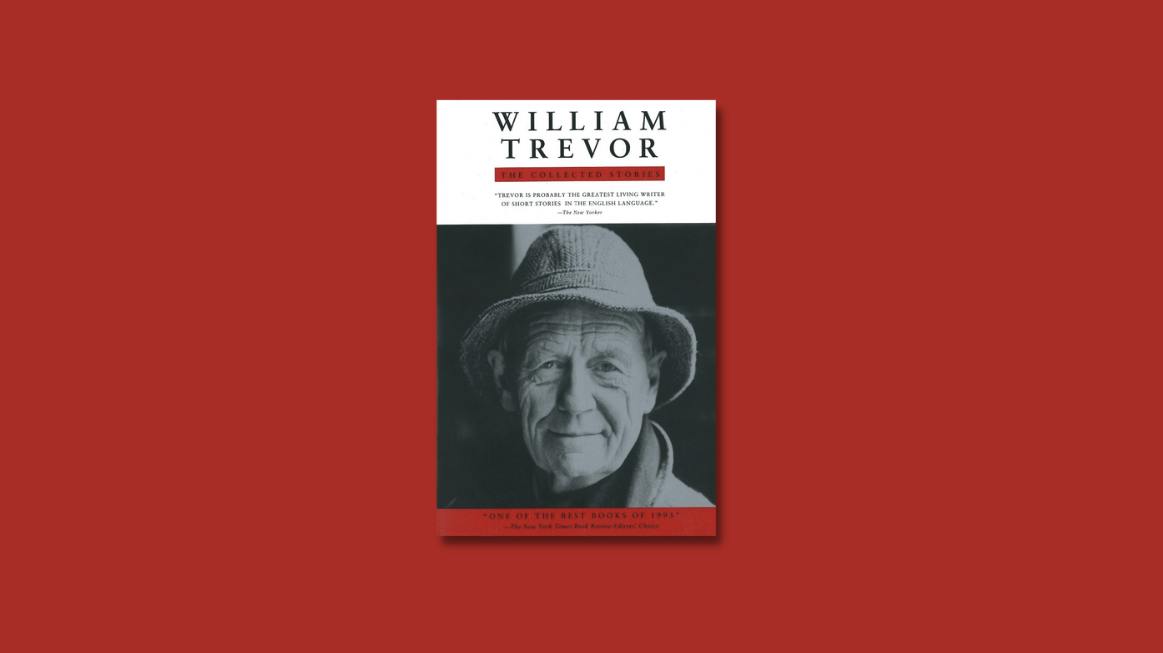

“A Dream of Butterflies” is an interesting one. It feels a bit hodge-podgey to me, a combination of several dominant Trevor story types, among them “People Forced to Account,” “A Long Uncomfortable Conversation,” and “Introducing an English Village.” The story unfurls in an unusual way, introducing multiple characters as they wake up with a sense of relief. They are relieved, we find out, because their village has successfully fought off the efforts of a Dr. Golkorn from buying a place called Luffnell Lodge from an elderly couple, the Allenbys. Dr. Golkorn, we learn in time (the story is cagey on this point—slightly annoyingly, in my reading) wants to establish a mental hospital for troubled women in the old manor house. The village is unified in their opposition to this idea, save for Mrs. Emily Mansor. Emily and her husband Hugh are established as the story’s two principal characters.

Emily is a classics teacher, an unattractive woman with a strawberry birthmark, referred to in the story via her own self-assessment as “dumpy.” Hugh is her attractive mate, a bit dim, who works in a travel office. They are both in their early fifties, near-retirement, and Dr. Golkorn identifies them as the weak link in the town’s resistance to his plans. He finagles an evening meeting with them, and in the course of it shames them into talking again to the Allenbys, whom Hugh has previously advised about the sale. Golkorn’s pressure point is that he is offering far more than any buyer would for Luffnell Lodge, and that it is unethical to advise this old couple against selling. The Mansors cave, but tell Dr. Golkorn he must understand that they will have to leave the village if they advise the Allenbys to sell, such will be the perceived treason on their part. We leave the Mansors as they approach the Allenbys at Luffnell Hall, feeling surprised at their gratitude to Dr. Golkorn for making them do the right thing.

Despite appreciating many of the more unusual qualities of this story, I feel like it doesn’t fundamentally work. The reason for this has to do with what I describe in my creative writing classes as the gears of conflict. Most fiction features two different forms of conflict: internal and external. I find it useful to imagine them as large gears, although typically of different sizes—in literary fiction, the internal gear tends to be larger than the external one. In effective stories, the gear of a character’s internal conflict synchs up with the gear of their external conflict. The gears turn from scene to scene, and as they do, they amp up the overall conflict and the dramatic stakes of the piece. An internal problem causes a character to behave in a certain way; this behavior causes an external problem that again amplifies the internal one. And so on.

This can occur in realist fiction, as with, to use a very obvious example, Carver’s “Cathedral.” The narrator is internally conflicted by feelings of inadequacy that manifest in hostility toward his wife’s visiting blind friend, Robert; these behaviors turn the gear of external conflict that result in interactions of surprising vulnerability with Robert that once more turn the gear of internal conflict, and we see the narrator change, if only to a small extent. This gears concept holds with non-realist stories. Cheever’s “The Swimmer” features a protagonist, Neddy Merrill, whose gear of internal conflict—also regarding his inadequacy and need to prove himself virile and capable—turns the gear of external conflict which sees him attempting to swim across his neighborhood’s pools, in doing so meeting increasing hostility from neighbors, which elevates his internal conflict and, ultimately, his self-perception.

The problem with “A Dream of Butterflies” is that, in my reading, the gears of external and internal conflict do not really mesh. The central internal issue facing the Mansors is their mutually held understanding that their partnership is based on their individual frailties. When Dr. Golkorn visits, Hugh looks at his wife and thinks:

Perhaps there was something in the fact that he had rescued her, he thought, wanting to think about her rather than their visitor. Even though she loved the subject, she had never been entirely happy as a teacher of Classics because she was shy. Until she came to know them she was nervous of the girls she taught: her glasses and her strawberry mark and her dumpiness, and the very fact that she was a teacher, seemed to put her into a certain category, at a disadvantage. And perhaps his rescuing of her, if you could so grandly call it that, had in turn given him something he’d lacked before. Perhaps their marriage was indeed built on debts to each other.

He considers this in the opposite terms, as well:

Could it be that Emily, so much cleverer than he, had found a level with him because her lack of beauty kept her in her place, as his inferiority complex kept him? She had said that as a girl she’d imagined she would not marry, assuming that a strawberry mark and dumpiness, and glasses too, would be too much for any man. He often thought about her as she must have been, cleverest in the class; while he was being slow on the uptake.

Of course, many if not most marriages are built on this sort of mutual indebtedness and compensation of weaknesses. But in this story, it is the reader’s central understanding of this marriage, and it is posited as—if not exactly a conflict or a problem per se—something to be worked out or elucidated or otherwise engaged with by the story. But the story’s external conflict, Dr. Golkorn and his hospital full of mental patients and the shame that will befall the Mansors for abetting him, has little to do with this internal problem of the Mansors’ marriage. One would expect the negotiation of this external conflict to apply pressure to Hugh and Emilys’ mutually protected weakness, the implicit arrangement of their union. Or else, we might expect the village’s ire at their surrender to Dr. Golkorn to say something about the similar shared frailty to communities, marriages writ large.

Instead, they decide at more or less the same time to assent to the Doctor, drive to meet the Allenbys, and feel as though they’ve made the right decision. All of the external action of the piece feels like it wants to turn an internal gear that doesn’t exist; namely, some moral shortcoming of the Mansors’, a shared need to do good at the expense of their friends in the village, a need for slightly extravagant ethical valor to replace something missing between them. But that internal problem does not exist in the story. And so you have the internal and external gears, unmeshed, prettily spinning on their own.

Next time around: “The Bedroom Eyes of Mrs. Vansittart.”