Funerals are battlefields of a different kind. Remembering the dead presents an opportunity to promote the cause for which they died.

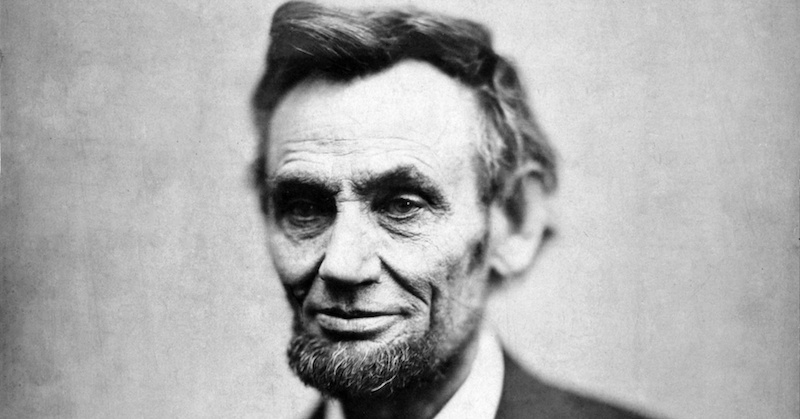

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address mastered the funeral battlefield. It quickly became the most famous and enduring eulogy in modern history. The president had spoken on November 19, 1863, to a crowd assembled on the grounds of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. The fields were filled with bones and other human remains; the stench of death was still in the air. Lincoln memorialized more than 3,500 fallen Union soldiers on that late autumn day.

“We have come,” Lincoln explained, “to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.” The soldiers had turned back a Confederate force invading Union territory, a force aiming to sack the nation’s capital and capture the president. Lincoln invoked the Union soldiers’ valor to inspire greater dedication from those still living “to the great task remaining before us”:

that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

The remembrance of the soldiers’ sacrifices boosted the cause for which they had fought. Their deaths were justified by the continued pursuit of something greater than their lives. And their memory, thanks to Lincoln’s soaring words, was now bound to the creation of an expanded, more inclusive democracy.

Remembering the dead presents an opportunity to promote the cause for which they died.

The funeral at Gettysburg transformed mass death into collective resurrection. Lincoln called it a “new birth”—a renewal of flagging Republican ideals, bloodied but pure, free from compromise and half measures that characterized standard political rhetoric. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address memorialized recent death to motivate expanded action.

For generations, Lincoln’s 271 words were widely read and spoken because they turned soldiers into martyrs. The president’s advocacy of a stronger, more inclusive democracy for more people passed from one generation to the next, a family heirloom and an article of faith that defined Republican Party politics for the next half century. Republicans, including millions of freed slaves, waved the bloody shirt of the sacrifices in the war to demand payment on the promise of democratic participation in the Union, for which their fathers had fought and died. Lincoln used death to demand freedom for generations of different citizens.

*

The president’s assassination deepened the memory of Gettysburg, attaching an indelible image to the inspiring words of his address. Undertakers worked feverishly to prepare Lincoln’s damaged body for public display. On April 18, 1865, three days after the president’s death, thousands of citizens lined up early in the morning to pay their respects, visiting the embalmed body in the East Room of the Executive Mansion.

The crowd was large and diverse—the largest to visit the president’s home since Andrew Jackson’s time in office thirty years earlier. Unlike in Jackson’s era, the visitors after Lincoln’s assassination included thousands of freed slaves and other African Americans, who, according to some estimates were more than half the crowd. Union veterans, widows, and children also visited in large number.

People came from near and far over the course of the long day. As the number of visitors continued to swell, officials hurried emotional people past the body. The air in the East Room was dense from the heavy breathing and tears of many onlookers. Some visitors cried out in pain. Numerous men and women wept as they passed the body.

Ushers struggled to silently control the distraught crowd. Many onlookers wanted to linger and pray. Lincoln’s body, limp and discolored, was venerated like that of a saint. By some.

The reverence for the slain president grew in coming days. On April 19, a horse-drawn hearse carried Lincoln’s body to the Capitol, where it lay in state in the Rotunda, under the nearly finished dome. The funeral procession imitated George Washington’s, sixty-five years earlier. A riderless horse, symbolizing the missing leader, followed the hearse. Thousands lined the streets, and the presence of African American soldiers was overwhelming. This might have been the largest multiracial crowd ever assembled, to that time, in the nation’s capital or any other American city. Booth’s nightmare of mass race mixing had ironically come to fruition because of his violent act.

Their memory, thanks to Lincoln’s soaring words, was now bound to the creation of an expanded, more inclusive democracy.

The mourning on April 19 extended far beyond Washington, DC. Cities and towns throughout the North and the West held public, multiracial processions to remember Lincoln. Even occupied Southern areas witnessed gatherings of white and Black Union soldiers to honor their late commander in chief. Shared grief united citizens, shocked by the assassination and shaken by the loss of their leader. Even those Union supporters who did not revere Lincoln before had trouble resisting the urge to glorify him in death.

*

“O Captain! my Captain!” wrote the poet Walt Whitman, describing how the martyred president’s demise cast a long shadow across the nation.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s surrender and Lincoln’s assassination, within days of one another, opened new uncertainties about the future of the country. As in any other period of prolonged and repeated suffering, citizens felt a disorienting mix of dread and anxiety, as well as relief and hope. What was happening, and what would it mean? Millions of Americans held tight to Lincoln’s paternal, religious image (“Father Abraham”) as an anchor of stability.

Whitman closed his poem with Lincoln’s body symbolizing both the hope and dread of the moment:

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

Confederate critics were moved by Lincoln’s death, but in a different way. They did not share the same grief as Whitman in Lincoln’s departure. He was their enemy, not their captain. He was not their president; that was Jefferson Davis. If Lincoln symbolized lost innocence and renewed promise for his followers, he embodied abolitionist degeneracy and Yankee tyranny for his adversaries. His assassination did not temper bitter and vindictive feelings. “Lincoln was a man of low, vulgar instincts,” the Texas Republican reminded its large reading audience shortly after his funeral.

The Union displays of fealty to Lincoln only reinforced the revulsion toward his image in the South. If anything, the public outpouring for the president in the North made him and his followers more threatening to Confederate critics. The Texas Republican condemned Lincoln’s supporters for “exulting over the supposed prostrate condition of the South.” The crowds mourning the president appeared dangerously poised to punish the region his assassin defended.

Lincoln’s inclusive democratic vision appeared more popular, and threatening, to opponents than ever. Expressions of sympathy for Lincoln, therefore, became highly dangerous political acts in the former Confederacy. One newspaper in the capital of South Carolina, burned during Union occupation, warned that Lincoln’s death could create a “pretext,” “eagerly seized upon by thousands at the North, to whom the sudden suspension of hostilities is a serious loss.”

Speculators will be glad to renew their games, practicing with their own wits upon the fluctuating moods of the country; soldiers will be glad of the pretext for rifling defenceless towns and villages; and thousands of jackals, in the wake of the tiger, will rush along our highways, gleaning whatever shall remain in the stores of the miserable population.

One week after Lincoln’s fateful visit to Ford’s Theatre, his embalmed and much-viewed body boarded a special nine-car train waiting at the New Jersey Avenue Station in the northwest corner of the nation’s capital. Four years earlier, Lincoln had first arrived there, lightly guarded, for his inauguration. Now he began his final journey home from the same spot, with a much larger crowd of spectators and a full train of three hundred dignitaries.

Lincoln’s inclusive democratic vision appeared more popular, and threatening, to opponents than ever.

Lincoln’s departure was particularly sad. He was murdered in his moment of long-suffering triumph. He died without an opportunity to leave a final testament or say his goodbyes. And he died heartbroken. The body of his eleven-year-old son, Willie, who died in early 1862 from typhoid fever, accompanied his father’s corpse on the funeral train. At the time of his assassination, the president and his wife had still not recovered from the blow of losing Willie.

The presence of the two bodies together, father and son, conveyed the suffering of the family—like thousands of other families—during the Civil War. The president had given so much personally for something much larger than himself. The Lincoln family pain on display to the nation was a pain many others felt.

Elizabeth Keckley, who remembered her suffering as a slave in Virginia before becoming a free woman in the Lincoln household, captured the sentiments of many former slaves: “No common mortal had died. The Moses of my people had fallen.

The shared sacrifice and pain made Lincoln’s remembered words personal, even religious, for those now mourning his death. His beautiful turns of phrase became literal as the weeping citizens observed the bodies: “Let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan.”

The message of Lincoln’s death to Union supporters was clear. There could be no “just and lasting peace,” as the president had promised, without continued commitment to the cause: what Lincoln had called “firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.”

_____________________________________

Excerpted from Civil War by Other Means: America’s Long and Unfinished Fight for Democracy by Jeremi Suri. Copyright © 2022. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of Hachette Book Group.