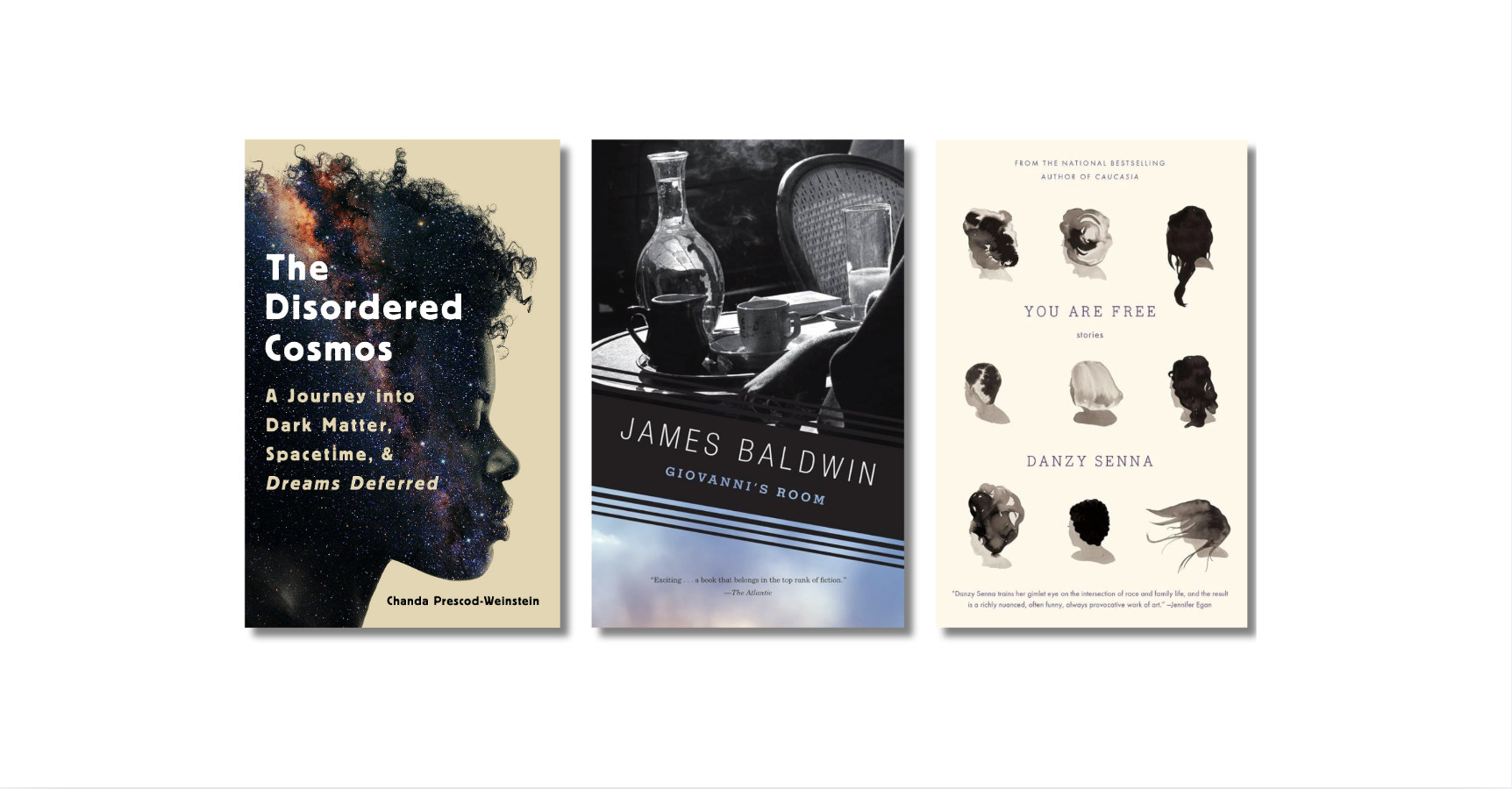

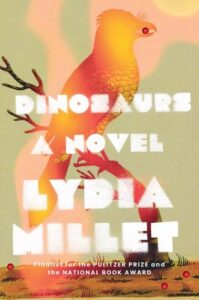

With typically acute wit, Lydia Millet self-identifies on Twitter as an “American novelist interested in apocalyptic thought, extinction, climate change and other lighthearted matters.” Her literary career encompasses twelve inventive, genre-bending, sometimes absurdist novels (including A Children’s Bible, a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award, Magnificence, a finalist for the 2012 National Book Critics Circle award, and My Happy Life, winner of the 2003 PEN Center USA award for fiction), two story collections (Love in Infant Monkeys, which features weird animal stories about Madonna, Sharon Stone, and other celebrities, was a finalist for the 2010 Pulitzer Prize), and three YA books, with an occasional freestanding offering, like the short story “Tylacine,” about the last Siberian tiger.

Millet’s cli-fi focus and questioning of capitalistic norms lead to rare insights into the 21st century human predicament. And she’s funny. In Oh, Pure and Radiant Heart, she writes with resonant irony of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, and fellow nuclear physicists Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi, who show up as houseguests in the “rich and leisured citadel of Santa Fe” circa 2003. (“Oppenheimer’s first full day at the motel was devoted to television. He located the remote on the bedside table, where it sat beside the enigmatic telephone with its sheet of intricate numeric instructions, and eventually by pressing the button marked power discovered its function.”)

Shifting to Florida in Mermaids in Paradise, she infuses a tale of the fight to keep newly discovered mermaids from being put on display in a new corporate theme park with equal parts hilarity and horror. In her new novel, Dinosaurs, she pares down the cast of characters to Gil, a lonely man who relocates from New York to the Sonoran desert, the family of four next door, a few extended neighbors, including an anonymous hunter illegally shooting wildlife, and the quail, screech owls, Harris’s hawks and other birds who share the habitat. Gil’s journey from sheltered innocence into an awareness of his place in a sometimes brutal world is finely wrought, with a touch of Candide. His moral quest also brings to mind the struggles at the center of novels of Saul Bellow, whose post-World War II-era characters tend to ask themselves, How should a good man live?

*

Jane Ciabattari: How has your life been during these past years of tumult and uncertainty, including wildfires? (I’m writing from Sonoma County, where fire season has expanded and I’ve been evacuated multiple times in recent years.)

Lydia Millet: You’ve had it tougher than me, so far. In the Sonoran Desert in southern Arizona, where I live, we have the looming specter of water shortage and the effects of drought and global heating on the ecosystems. We have suspicions, supported by a measure of science, that the great saguaro cacti that define the landscape are dying too fast and not reproducing enough.

I like our fascination with those creatures who died off so long ago.

And that things are beginning to bloom at the wrong times of year. Trophic mismatch. On that front I only have anecdotal evidence. Sometimes we have the sight of fire up at the higher elevations. But few evacuations, yet. One friend of mine was under an evacuation order in the last big fire in the Catalina Mountains over Tucson. She refused to leave. And as it turned out, her house didn’t burn. Or her land. So she got lucky.

JC: When did you begin writing Dinosaurs? What was the impulse that began the process?

LM: June 2018. I wanted to write a simple story about a lonely man and a welcoming family. I’d been, before that, writing more complicated stories with many events in them. But the events are never the part that counts to me. So I thought, how about try a straightforward tale, for once. With a guy who can see into his neighbors’ place the way you look into the open side of a dollhouse. Or watch a play.

JC: Why the title?

LM: Simple story, simple title? Except that nothing about dinosaurs, or any other extinct beings, is truly simple. Semantically or ontologically. I like our fascination with those creatures who died off so long ago. How we reconstruct their bodies and play with them, when we’re kids. Put them up on pedestals in museums, when we grow up, or go to those museums and gaze at them. Try to imagine their life cycles and behaviors and world. And how, at the same time, their descendants are still living all around us. As birds. In our suburban yards and on our city balconies. So they’re gone and they’re present. In a form that’s been dramatically altered by deep time.

JC: You begin with Gil, an orphaned man who has inherited a fortune from deceased parents, recently out of a relationship, walking from New York City to the Arizona desert—“the opposite of Manhattan,” to settle into a new house, sight unseen. What drew you to tell his story?

LM: My boyfriend Aaron, who’s otherwise a far cry from Gil—for example, he’s worked in construction most of his adult life, rather than being an heir to a fortune—had walked a long way just before I wrote the book. The whole Appalachian Trail. I watched that months-long journey unspool through my phone. Pictures and videos of snakes and slugs and black bears, of stormy mountaintops and old, old cemeteries in the woods. And its solitude and persistence stuck with me.

I was an occasional assistant to the hike, doing the odd favor like sending new shoes across the country for him to pick up at a mail drop, but he would have achieved it with or without me. And not long afterward he moved from New York City to Arizona, as Gil does. So I combined the two. Stealing a long walk and a move from Aaron’s life. I also stole from his hike for A Children’s Bible, incidentally—the “trail angels” who leave water for thru-hikers. That’s a real thing and a real name.

JC: Gil’s closest neighbors in a bastion of relative wealth live literally in a glass house. Their relationship involves interweaving and overhearing. How do you envision the role of boundaries in maintaining harmony?

We make borders where we shouldn’t, on the macro scale, or treat them in ways we shouldn’t.

LM: Ha! Crucial. Existentially necessary, on a personal level. Without them we would lose our hold on reality. But of course, on the macro level, they’re also pure fabrications, barriers made of power and for the sake of it. And the sites, in our landscapes, of a distressed and ugly politics. We make borders where we shouldn’t, on the macro scale, or treat them in ways we shouldn’t. And we don’t make them where we should, on the micro. And in places like social media. We’re chaotically confused when it comes to boundaries. We have both too many and too few.

JC: Despite his relative isolation, Gil connects with others—the family next door, a woman he dates, troublesome neighbors. Do you find that distilling your cast of characters to a few offers sharper contrasts in behavior?

LM: Sure, sharper contrasts and greater lucidity. Fewer is better, often. With casts. Although too few is potentially boring. Somewhere between sprawling and boring is where I was aiming.

JC: I was thinking about A Children’s Bible in contrast to a single guy next to family of four, plus neighbors…

LM: Yes, exactly, right. Children’s Bible was a mob scene!

JC: Tom, the ten-year-old next door, represents the younger generation, those you highlighted in A Children’s Bible. Tom seems to offer Gil a substitute for a normal childhood, and also a form of parenting or mentoring. Gil caters to Tom, who avoids meat to “help the animals and lower their carbon footprint.” Did you intend a parallel between Gil and Tom as they learn to maneuver through a complicated world that includes violence and conflict?

LM: Socially Gil’s an innocent, to some degree. Like Tom. One of them’s an adult and the other’s a child, but they’re on parallel tracks for sure. Learning to stand up to bullies. A lesson I still haven’t fully learned myself. Bullies exist at so many levels of social and economic life. For some of us it’s easier to confront them in person; for others, in the abstract. But few of us do either of these as often as we should.

We’re chaotically confused when it comes to boundaries. We have both too many and too few.

JC: Gil gradually opens up to the world outside his house, a strange world to him, with saguaro cacti, jumping cholla, and birds. “The walk was when he first noticed birds…. Birds were descendants of dinosaurs, they’d taught him in college.” He muses on recent discoveries in paleontology as readily as he does on the Harris’s hawks and quail he encounters. Is this a teaching element in the work?

LM: Oh, I hope not.

JC: How has your own life in the Sonoran Desert outside Tucson and your work at the Center for Biological Diversity infused and influenced this novel?

LM: I love where I live and I love where I work. Both are a privilege and an honor. All the birds in the book are birds I know from my own yard. Like Gil I was bored by birds when I was younger. Flit, flit, flit, yawn. But now, like Gil, I watch them and wonder at them. Birds are such perfect animals in their design. Imagine being able to fly thousands of miles without eating! Or remember a map of every single plant you’ve ever taken nectar from. Though your brain is the size of a grain of rice! They’re straight-up miracles of evolution. Among its many other miracles.

JC: What are you working on next? More fiction? More work at the Center? Essays?

LM: Yes, the Center is my day job for thirty hours a week. So I always work at that. I’m finishing a book of short stories now, along with a nonfiction book that’s somewhere between a memoir and a bestiary. And I’m doing a new novel.

__________________________________

Dinosaurs by Lydia Millet is available from W.W. Norton & Company.