Dan Preston logs in to our video call in a respectable, nondescript button-up shirt. His personal style may lean toward the conventional, but the Rice University mechanical engineer is here to tell me about his creative new fashion design. His team has made a shiny black jacket that performs logic—without electronics. Specifically, the jacket can raise and lower its own hood at the push of a button, and it contains a simple 1-bit memory that stores the state of the hood. Or, as Preston says, it’s “a non-electronic durable logic in a textile-based device.”

Here’s where we need to emphasize the wildness of this design. The hoodie does not contain an Arduino or any semiconductor chips. It has no batteries. Preston and his team have cut pieces of commercial nylon taffeta fabric and glued them together to form inflatable pouches about half the size of a business card. Connecting the pouches with small soft tubes, they have embedded them into the jacket. Pressing buttons on the jacket controls the flow of air from a canister of carbon dioxide through the pouches. The pouches fold and unfold to form kinks that either inflate or deflate an airbag in the hood to make it rise and fall.

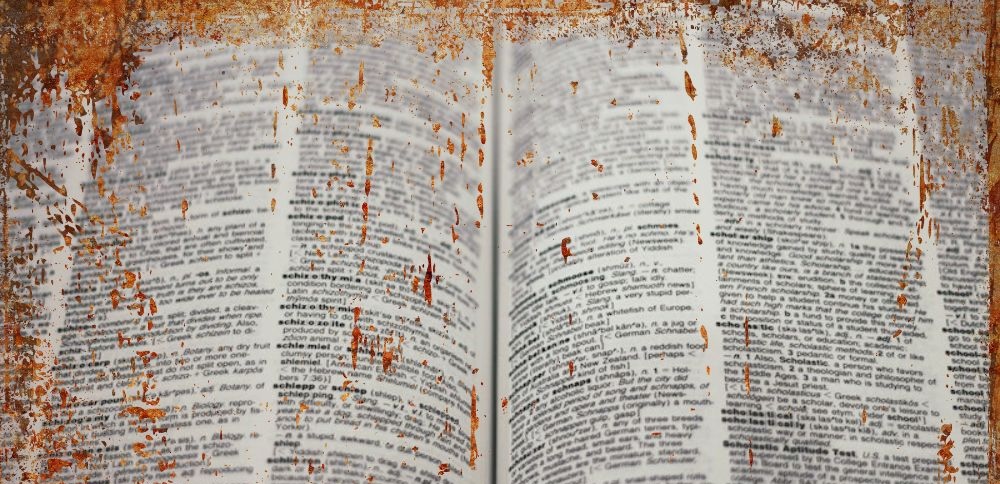

Courtesy of Dan Preston

At first glance, the jacket seems more like a bike tire than a computer. But you can think of the air-filled pouches on the jacket as analogous to electronic transistors, says Preston. In an electronic circuit, transistors control the flow of electrons, or electric current, based on the voltage in the circuit. “We’re just replacing voltage with pressure, and we’re replacing current with the flow of a fluid, which is air in this case,” he says.

For example, the team created an air-based NOT gate. In an electronic circuit, a NOT gate receives some input—say a 1, corresponding to a high voltage—and changes it to a 0, or low voltage. In the hoodie’s case, the air going into a pouch might be at high pressure, and the pouch can convert it into a low pressure, or vice versa. The technology originates from Cold War defense applications, when engineers designed air-based logic devices because adversaries could not interfere with them using electromagnetic pulses.

“I’m really happy to see people moving radically beyond the cutting edge in wearables,” says mechanical engineer Michael Wehner of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in the work. The team’s use of fabric and air-based logic, also known as pneumatic logic, is particularly novel. Wearables, like the Fitbit and Apple Watch, are usually “modest adaptations of traditional devices,” says Wehner.

The jacket falls under the category of “soft robots,” which are automated, programmable machines made of flexible materials such as rubber, silicone, or fabric. In recent years, researchers have begun designing soft robots to potentially work alongside humans. They generally move with less precision than their hard metal counterparts, but they have a gentler touch. “If you’re working and a [hard] robot hits you, you go to the hospital if you’re lucky,” says Wehner. “If a soft robot—this big airbag—hits you, everyone laughs and has a good time.”

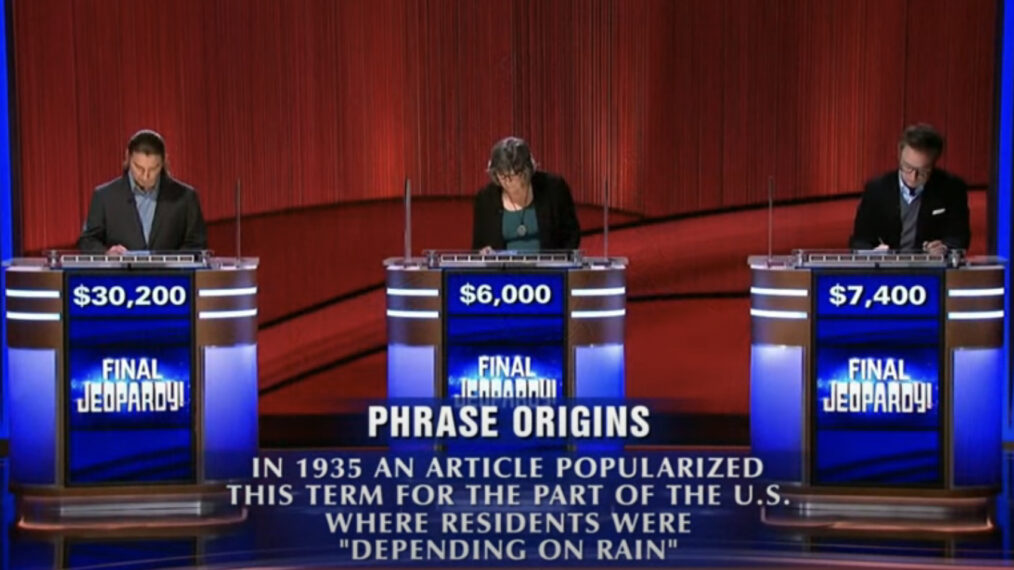

Courtesy Dan Preston

In other words, soft robots should more easily and safely integrate into regular human activity. Because Preston’s logic elements are made of fabric, the intelligent jacket feels more like a regular one than a coat filled with electronics or other hard components. “It is very easy for humans to adapt to it and not feel like they are wearing something weird,” says mechanical engineer Wenlong Zhang of Arizona State University, who was not involved with the work.

In addition, a fabric computer is more resilient than a semiconductor-based one. To test the jacket’s robustness, the team placed a component made of several fabric pouches in a mesh bag and ran it through a washing machine 20 times. They also ran it over with a 2002 Toyota Tacoma pickup truck—scenarios “you might expect a traditional piece of clothing to encounter at some of the extremes in its lifetime,” says Preston. The pouches still worked. Imagine doing that to an Apple Watch.