Camilo Garzón: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Camilo Garzón.

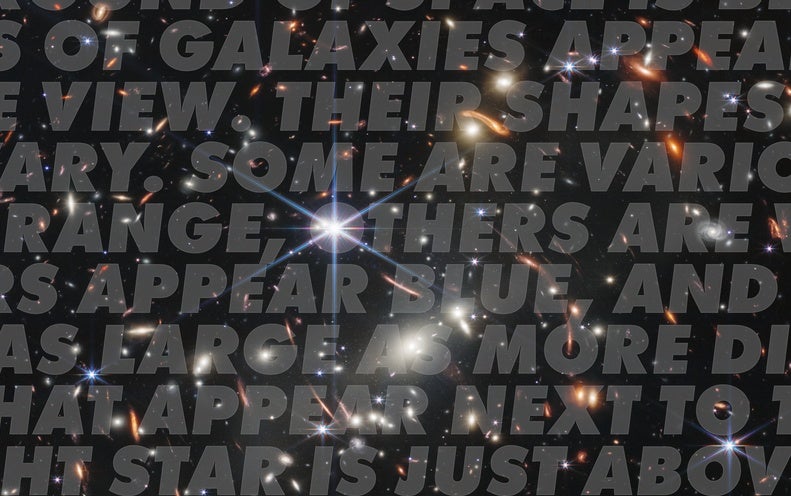

In July, The White House released the first image of the collection of pictures from the James Webb Space Telescope – the JWST – during a preview event with President Joe Biden.

Joseph R. Biden, Jr.: Six and a half months ago, a rocket launched from Earth carrying the world’s newest, most powerful deep-space telescope on a journey one million miles into the cosmos … it’s a new window into the history of our universe. And today, we’re going to get a glimpse of the first light to shine through that window…

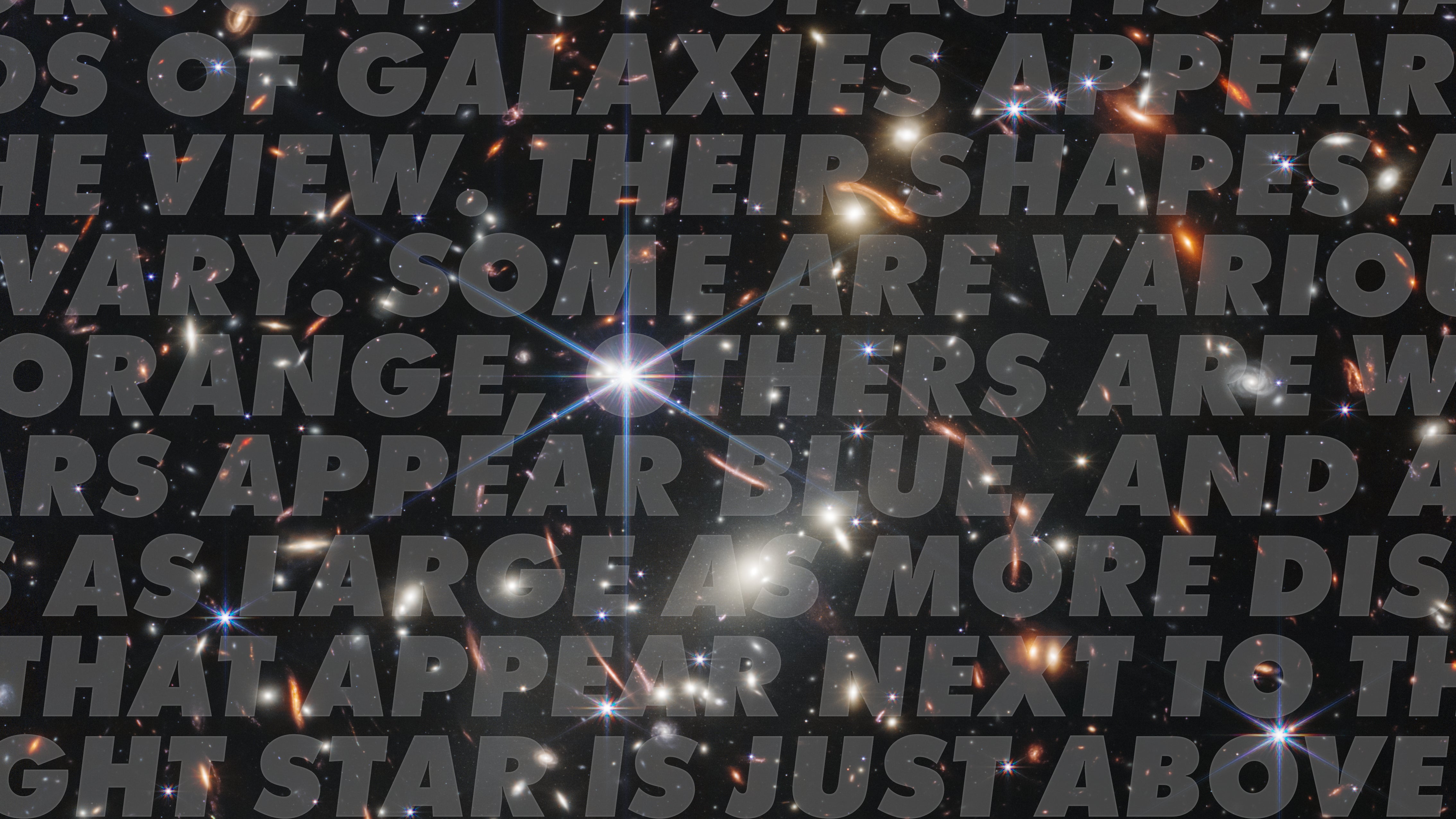

Garzón: It was a high-resolution image of a cluster of distant galaxies known as SMACS 0723. It was the deepest, sharpest infrared image of the universe, ever.

The image had to be seen to be believed–and on that day, it was everywhere to see and ponder, from the big screen in Times Square to trillions of small screens across the world. But, what if you are physically unable to see it?

Claire Blome: SMACS 0723. The background of space is black. Thousands of galaxies appear all across the view. Their shapes and colors vary. Some are various shades of orange, others are white. Most stars appear blue, and are sometimes as large as more distant galaxies that appear next to them. A very bright star is just above and left of center. It has eight bright blue, long diffraction spikes.

Garzón: Descriptive. Scientific. And if you were unable to see, you would, for the first time, be able to construct a mental image of what the rest of the seeing world saw.

Blome: When I think about people listening to the ALT text … I want it to be like listening to a book where you imagine the scene, all the characters in the scene, and in these cases, it might be galaxies and stars as the characters, all the activity in it.

Garzón: That’s Claire Blome, principal science writer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, the operations center for the Webb telescope.

And ALT text, as you might have gathered, is an official way to describe, and make accessible, the contents of an image to someone that might not be able to see it with their eyes.

In 2020, it was estimated that over a billion people on earth live with vision impairment. That’s according to the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. So, if many millions around the world were following the news of Webb’s first image, the number of viewers who couldn’t actually view it was likely significant. That image’s ALT text has likely been heard by multitudes.

But ALT Text can go further than just visual description. It can even add context to an infographic or a graph that might not be clear to all that take it in, whether by looking at it, or listening to it described. At its best, ALT text also helps…

Carruthers: … fill in the gaps for what you might be missing if you can’t access the whole image completely.

Garzón: Margaret Carruthers, also of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Blome: Everyone’s perception is different. Details of the science might be evident to an astronomer or scientist but it is not going to be immediately evident to a member of the public who does not have that educational background.

Garzón: That’s Claire Blome again.

Blome: So that’s why it’s so important that we had a team of educators and scientists going through and just double checking us. Did we cover everything? But also did we attempt to describe some of the science because that might need to be removed because it shouldn’t be accessible to anybody in that alternative description?

Garzón: Both Blome and Carruthers say that ALT text represents a merging of science and art. But it’s also critical work, because no one should be left out of the experience of taking in our universe in a new way.

Blome: For me, it’s a bit of awe first, but then, okay, that’s the hook now you’re into this. Let me tell you what’s here. So then being able to describe, for example, the star at the center of a planetary Nebula, and then describing the scene of gas and dust around it, you know, being able to compare it to, you know, wispy or translucent fabrics.

Even if somebody hasn’t seen fabric blowing in the wind, they perhaps have felt it and understand the differences in the weights of fabrics. But either way, the goal is to paint a picture with the writing to be complete, to provide the whole as much as possible. It’s not a one to one, but it’s providing someone that same in-depth experience–that opportunity.

Garzón: A kind of adaptation and translation that still communicates and paints a picture as well as it can. Carruthers agrees…

Carruthers: It is very much like a translation where say somebody translating poetry focuses on, you know, one word over another to kind of convey the feeling or the intent of the poetry.

Garzón: For the Webb’s first images, they wrote descriptions that were both scientifically accurate, illuminating, and I might even say: poetic.

Here’s Blome reading one of her favorites:

Claire: This frame is split down the middle. Webb’s mid infrared image is shown at left and Webb’s near infrared image on the right. The mid-infrared image appears much darker with many fewer points of light. Stars have very short diffraction spikes. Galaxies and stars also appear in a range of colors, including blue, green, yellow, and red. The near infrared image appears busier with many more points of. Thousands of galaxies and stars appear all across this view. They’re sharper and more distinct than what is seen in the mid-infrared view. Some galaxies are shades of orange while others are white. Most stars appear blue with long diffraction spikes, forming an eight-pointed star shape. There are also many thin, long orange arcs that curve around the center of the image.

Garzón: Beautiful.

Here’s Carruthers reading one of hers:

Carruthers: The background is deep blue with scattered points of light of different size and brightness running from left to right through the middle is a jagged line representing a light spectrum, a graph of brightness versus wavelength of light. The area below the spectrum has a rainbow pattern from red on the left to purple on the right. The coloring is semi-transparent. The blue starry background is visible behind, and fades out toward the bottom. In the middle, superimposed on the star background and part of the spectrum, is a large hexagon outlined in gold with two hexagonal outlines.

Within the hexagon is an illustration of space with shapes representing objects and materials at different distances and points in time that Webb is investigating. A large planet with hints of cloud formation. Beams of matter, jetting out from the center of a galaxy. Galaxies of different shapes and sizes, nebulous, cloudy, widths, and stars with eight pointed diffraction patterns.

Garzón: Thanks to the team from the Space Telescope Science Institute for describing these jaw-droppingly beautiful images in such a powerful and scientifically accurate way.

For Scientific American’s 60-Second Science, I’m Camilo Garzón.

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]