Trees in many parts of the Brazilian Amazon are being cut down and burned to make space for agriculture Kristof Bellens/EyeEm/Alamy

Indigenous leaders from the nine countries and territories that encompass the Amazon region have presented a report today that says so much of the rainforest has been lost that it has reached a crucial tipping point, that would turn forest to savannah, earlier than expected.

Vast swathes of the southern Amazon rainforest have gone and the rest will follow if deforestation isn’t halted, the leaders told the fifth Summit of Indigenous Peoples in Lima, Peru.

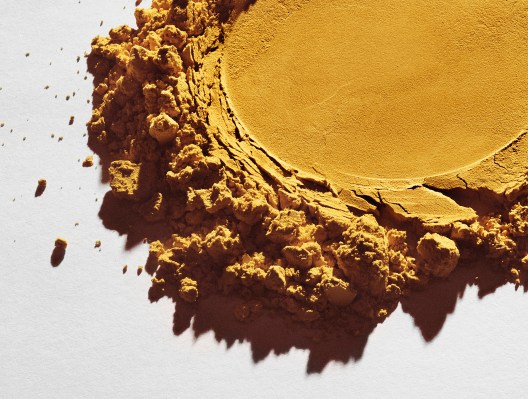

Researchers have predicted that once a certain amount of the Amazon rainforest is lost, it will no longer be able to hold the necessary moisture and generate the rainfall it needs to support itself. This would set off a chain reaction as the world’s largest rainforest transforms into a savannah incapable of regenerating itself.

When this tipping point will occur is unclear, but 2019 work found that 17 per cent of the Amazon basin’s rainforest had been lost, and an estimate from 2018 put the future threshold at about 20 to 25 per cent of combined loss and degradation.

Surging deforestation in recent years means that threshold has already been passed, finds the latest report. It says that about 20 per cent of the Amazon has been cleared and another 6 per cent highly degraded in about 35 years.

Marlene Quintanilla at the Amazon Geo-Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG) and her colleagues, working in partnership with various groups, including the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin, used forest coverage data to map how much of the Amazon was lost between 1985 and 2020 and also looked at forest density, rainfall patterns and carbon storage.

The rainforest’s abilities to store carbon and regulate precipitation are indicators of its capacity to survive, says Quintanilla, and studying them can also reveal the effects of forest fires beneath the canopy, which satellite images can miss.

The report finds that 33 per cent of the Amazon remains pristine and 41 per cent of areas have low degradation and could restore themselves. But 26 per cent of areas have been found to have gone too far to restore themselves: 20 per cent is lost entirely and 6 per cent is highly degraded and would need human support to be restored.

“The ecological response of the forest is changing and its resilience is being lost,” says Quintanilla. “We are at a point of no return.”

The Amazon may span 847 million hectares, but distant regions are highly interdependent. Losing trees in one area of the rainforest means there is less rainfall, higher temperatures and less CO2 absorption in others, which makes them more susceptible to fires and less resilient to climate change, feeding back into the cycle of destruction.

The transformation is already visible in Brazil and Bolivia, say the report’s authors. These two nations account for 90 per cent of all combined deforestation and degradation in the Amazon.

In the past 20 years, rainfall in parts of the Bolivian Amazon has reduced by 17 per cent and the temperature has risen by 1.1°C. Areas of dense rainforest are becoming savannah and trees in the north of the country have stopped producing the fruits that uncontacted Indigenous groups depend on to eat, says Quintanilla.

If agriculture, mining and other drivers of deforestation don’t cease, that process will spread quickly to other countries, say the authors.

About 86 per cent of deforestation has occurred in areas outside national or Indigenous reserves, and given that 48 per cent of the Amazon remains unprotected by reserves, those areas will be lost unless they are given protection, say the researchers.

Indigenous reserves were found to be slightly better conserved than national parks, despite having less government investment and support. So the authors suggest that the best way to save the rainforest is by designating unprotected land as Indigenous territory.

Efforts should also be made to restore the 6 per cent of rainforest (54 million hectares) with high degradation, say the authors, to prevent the Amazon becoming savannah.

Carlos Nobre at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil has been running climate models for three decades to understand when the Amazon could reach its tipping point and how it could look.

“Unfortunately what we’re seeing today is no longer based on models. What we are seeing today is observations across the entire southern Amazon that indicate that the risk of this tipping point is immediate,” he says. “The RAISG study showing the high levels of deforestation and degradation is very, very, very worrying.”

The length of the dry season in the southern Amazon, which makes up a third of the entire rainforest, now lasts four to five months, five weeks longer today than it was in 1999, says Nobre. If it reaches five to six months, it will no longer survive.

Sign up to our free Fix the Planet newsletter to get a dose of climate optimism delivered straight to your inbox, every Thursday