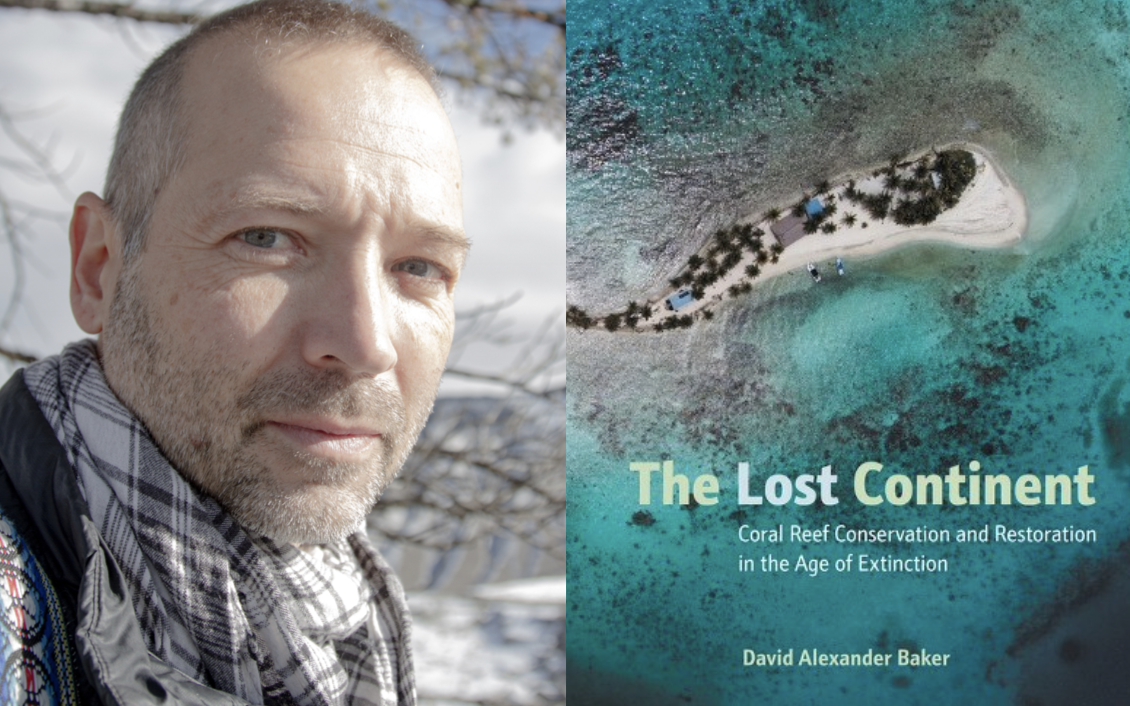

David Alexander Baker’s The Lost Continent: Coral Reef Conservation and Restoration in the Age of Extinction explores one of the planet’s most fascinating and highly threatened biomes. While acknowledging the impending climate catastrophe that coral reefs face, Baker writes with a sense of awe for nature’s beauty and hope for its future, reflecting on his own diving expeditions along the way. We talked with Baker about his work as a documentary filmmaker and media production team leader at Oregon State University, the importance of biodiversity, and how we all can help conserve the planet’s coral reefs.

The Millions: What was the genesis for The Lost Continent? What led you to write this book, and what was its path to publication?

David Alexander Baker: A few years ago, I made a documentary about the decline of coral reefs called Saving Atlantis with my filmmaking partner, Justin Smith. The aim was to raise awareness about the pressures driving the destruction of reefs, as most of them are caused by humans. After 90 minutes of content was edited down from hundreds of hours of interviews and footage, there were stories we left on the cutting room floor and tangents we hadn’t explored. I thought a book would be a great way to deepen my understanding, explore new narrative threads, and get the topic in front of a wider audience, because the problems facing corals aren’t going away. Oh, and I also needed an excuse to dive on more reefs—they’re simply the most stunning landscapes one can imagine.

TM: Your background is as a science documentary producer—what led you to start diving?

DAB: I never know what sort of film project will come next. My production team works with scientists on the grant cycle: a researcher proposes a project to an agency like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and waits to see if it gets funded. One requirement of the NSF is that the scientists are supposed to communicate the impact of their research on society. That’s where my team comes in. We do that storytelling to explain what’s happening and why it’s important. So we pitch films to accompany these large research grants. About a quarter of those project proposals end up getting funded, and that’s when we get the green light for a film.

In the case of diving, my partner Justin met a coral researcher at a cookout. We drafted a concept for a series of short films, submitted the proposal and then forgot about it. A year later, the scientist emailed us—the project had received funding. We were to accompany her team to the South Pacific, Australia, and the Red Sea to document their work studying the coral microbiome. That’s when she told us that we needed to learn how to dive if we wanted to film below the water. Neither of us had ever so much as pulled on a wetsuit. And the budget wouldn’t allow us to hire an underwater cinematographer: we had to do it ourselves.

So, we started training. We had to become certified science divers to accompany the team, which is a pretty advanced level. We had just three months. And it was the Pacific Northwest. In the winter. All through that ordeal we were freezing in the bottom of the Puget Sound in leaky rental wetsuits, wondering why anyone would ever take this activity up as a hobby. But then we earned our credentials and I remember very vividly plunging into the water above my first massive reef wall in the Red Sea, and it all came together: the warm water and the spectacle of corals. Diving opens up an entirely new universe. It’s transformative.

TM: In your adventures diving, what was something surprising that you witnessed or discovered?

DAB: To me, biodiversity is the most staggering thing about coral reefs. 25 percent of all marine species spend time on coral reefs, even though these ecosystems take up less than 0.1 percent of the earth’s surface. And you only truly understand this if you look close and can hover in one place for a long time to study the details. From the fish to the algae and the myriad invertebrates all the way down to the microbes, there is more diversity of life in a square meter of coral reef than just about any other system on the planet. They’re called the rainforests of the sea, but in truth corals are much more ancient forms of life than even the flowering plants that make up the rainforests. And hovering in the clear water where reefs thrive, you can see fish threading the branches and worms dancing through the grooves. It’s a staggering variety of living shapes and colors. Coral reefs are impressive in their massive size—some are hundreds of miles long. But it’s the detail that’s really surprising.

TM: In The Lost Continent, you say that the Varadero Reef in Colombia is the most fascinating you’ve ever seen. Can you talk more about why?

DAB: Varadero is located in the Caribbean Sea at the mouth of Cartagena Bay. It’s one of the most polluted spots around. It’s covered with a cap of murky sediment that flows out of a 500-year-old shipping canal built by the Spaniards. Corals usually don’t like turbid water. They thrive in clear water, and the farther away from people, the better. Reefs all over the Caribbean have been hammered by human pressures for decades. Corals have bleached, been overfished, dumped on, ripped out and dynamited. Florida reefs have about 2 percent of the historic coral cover remaining. Even the magnificent reefs in Belize are at around 17 percent. But Varadero has 80 percent coral cover or more. I’ve never seen anything like it.

When you dive on Varadero, you submerge through this cap of murky water, but all that sediment stays at the top few meters. Then the visibility clears up. So as you slip down, you see this vast landscape of unexpectedly healthy corals open up beneath you. The cap of murky water does strange things to the light. And the shapes of the coral colonies are odd: they have the radar-dish growth forms of corals that live in much deeper water. One theory I’ve heard is that the murky water shields these corals from light and tricks them into behaving as if they’re much deeper than they actually are. Somehow, this has allowed them to thrive in this unexpected location right next to a major metropolitan area and surrounded by shipping lanes. With enough research, we could learn some secrets from Varadero. The frightening thing is that this reef has been threatened by development. I hope the Colombian government understands that Varadero is a natural wonder unlike anything else on the planet.

TM: More than half of the world’s coral reefs have been destroyed in the past 50 years due to climate change. What specific forces have conspired to decimate coral reefs, and how have you witnessed examples of this devastation firsthand?

DAB: There are natural processes that wear down reefs: storms, waves, changes in weather like El Niño and La Niña events. And corals have evolved magnificently to grow and rebuild after these natural pressures. But humans have changed the game by altering the climate through the burning of fossil fuels. This warms the ocean and the carbon is making the water more acidic. Corals live at their thermal threshold, and if it gets too warm for too long, they will bleach and often die. Increasing acidity can weaken their capacity to build their stony skeletons.

Industrial scale harvesting of fish also takes a toll. If you remove all the herbivorous fish that keep the plants in check, then algae can take over and choke out the corals. Pollution and nutrient runoff from rivers harms corals and feeds algae, turning reefs into slick, green muck. Climate change supercharges storms and makes them more violent and frequent, grinding down reefs to the point where their natural recovery can’t keep pace. Resort developers will sometimes smother reefs with sand to make a beach or even dump construction debris right on corals. The pressures are legion. But the good news is that we’re causing most of the decline. So that also means we have the power to stop it. We can control these pressures through our actions, if only we can muster the political will.

TM: Often, conversations about conservation focus on individual behaviors, like not using plastic straws or driving a hybrid car. Lifestyle choices are important, but the actions of large corporations, which have a much larger impact on the environment, rarely receive the same scrutiny. (One study even posited that just 90 companies are to blame for most of climate change.) What sort of larger scale changes, besides just recycling our soda cans, would you like to see to safeguard our planet?

DAB: The fact is that we all will have to alter our behaviors en masse if we want to save stony, reef-building corals from extinction. They’re the canaries in the coal mine of climate change. So there are lots of individual things we can do to contribute to solutions that might save them. We can eat lower (and healthier) on the food change, which means more plants and less meat. We can bike to work, put up solar panels and everything you mention to control carbon and pollution. But the problem with making the solutions a matter of individual responsibility is that it lets large institutions, like governments and corporations, off the hook. There are forces that love it when we squabble and count each other’s carbon while they continue to chase easy profits.

So ultimately, we need societal change: a transformed energy and economic system, protecting and restoring natural ecosystems on a global scale and ethically addressing the world’s exploding population. None of these things can be accomplished by individuals. We need a mass movement and a groundswell of support for making sweeping changes. And I think that’s where my little piece of the puzzle comes in. If I didn’t believe that narrative, storytelling, and imagery can help move the needle in building support for such change, I wouldn’t be in this line of work. Corals can be the characters in the story about what we need to do on a global scale to stave off biological collapse.

TM: The Lost Continent takes readers to reefs around the world, from the Caribbean to Red Sea. Though many readers might not live anywhere near coral reefs, you make the case that they are still pertinent to all of our lives and deserve our protection. Why should everyone care about coral reefs, regardless of where they live?

DAB: Half a billion people get their only daily protein from reefs. And many commercial species we eat use reefs as nurseries. We need them to feed us. The good news is that the solutions that will save corals are also those that can protect all life on our planet, including our own. Biodiversity loss is happening in terrestrial as well as marine habitats. Ecosystems from wetlands to forests and rivers are vanishing. The very systems that provide our food are imperiled. Coral loss has been involved in all the major mass extinctions over hundreds of millions of years. These animals are telling us something important through their struggles. By making the changes needed to protect them, we’re helping ourselves. If they collapse, other systems will follow, and the future will be bleak for our own species.

TM: The Lost Continent is divided into three sections, the last of which is called “Searching for Hope.” It’s often hard to be hopeful when it comes to matters of the environment, and especially coral reefs. What gives you hope?

DAB: This is the biggest challenge when it comes to covering environmental topics. How do you communicate the urgency and the dramatic scale of the losses without turning people off or giving in to despair? Chris Johns, the former editor-in-chief of National Geographic Magazine, calls it, “balancing the wonder with the worry.” So in that sense, the wonder—the sheer beauty and the ingenious functioning of these elaborate ecosystems—gives me hope. Corals are animals, but they have symbiotic plants living inside of them, and together these tiny life forms undertake the largest construction projects on the planet—rocky structures that put the Manhattan skyline or the Great Wall of China to shame. And there’s wonder in the corals’ resilience. Varadero proves that. They can surprise us, if we give them space to evolve. The corals of Varadero have lived with humans for 500 years, and they found a way to adapt and thrive right alongside us.

And finally, there are the people working on solutions. Humans are the problem, but we are also the great hope. For this book I interviewed so many scientists, activists, fishers and indigenous community leaders who are paving a path forward with hard work, traditional knowledge, research and education. The human capacity for empathy, drive and creativity is boundless, even in the face of such long odds.