[The following story contains spoilers from HBO doc The Janes.]

When a draft opinion from the Supreme Court leaked last month, suggesting the court could be poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, the directors of underground abortion network documentary The Janes, which premiered on HBO on Wednesday night, were stunned.

The moment reflected the duality that helmers Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes have experienced as they made the film in recent years. “It’s this in-between place of being fully aware and in disbelief of everything that’s happening,” Pildes tells The Hollywood Reporter.

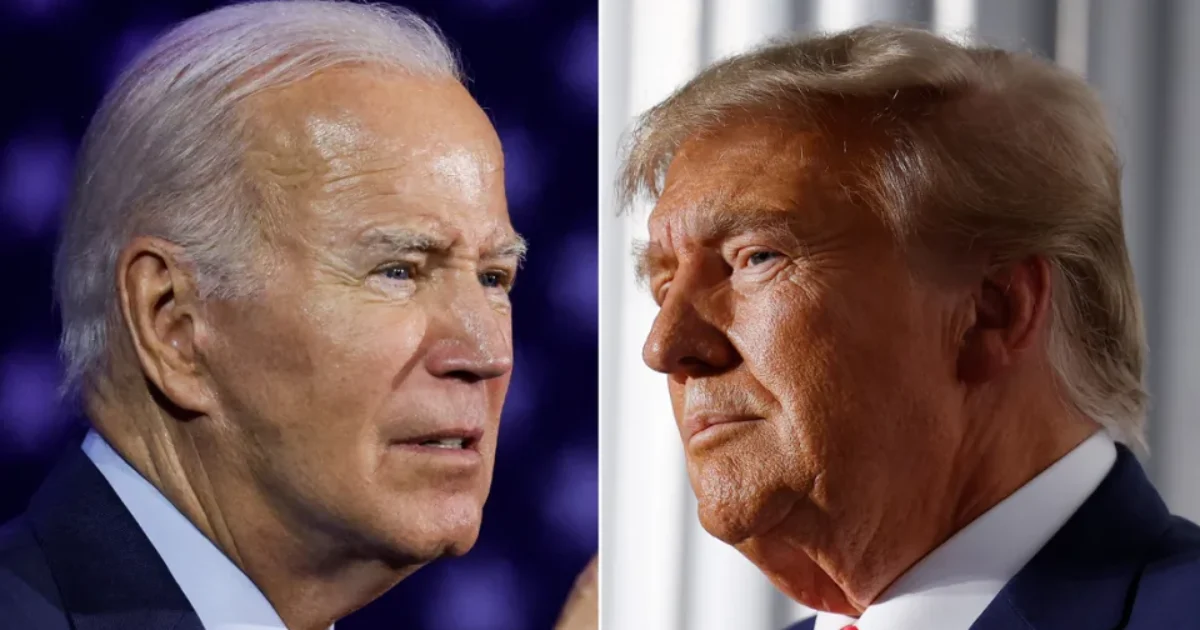

The Janes producer Daniel Arcana, whose mother was one of the members of the Jane Collective featured in the documentary, started developing the project shortly after former President Donald Trump was elected. “He was prescient. He saw, like so many others, that this story needs to be told,” Lessin tells THR.

Pildes, who happens to also be Arcana’s sister, and Lessin began collaborating on the film after Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings. Lessin explains that Kavanaugh being considered for the Court, along with Trump’s other appointees Neal Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, “all pointed to the fact that Roe was not long for this world.”

“We were soon, in this country, going to be facing conditions very much like what the Janes faced in the ’60s and early ’70s,” she said. And that political atmosphere made the “intrinsically dramatic” story of “ordinary women turned outlaws” timely. “They were risking arrest and a lifetime in prison at a time when abortion was illegal, and it seemed to really speak to the moment.”

The film, which premiered at Sundance, features first-hand accounts from the women at the center of Jane, a clandestine Chicago group that helped women obtain safe, affordable abortions in the late ’60s and early ’70s when the procedure was a crime in Illinois and other states. Seven of the members of Jane were arrested and charged with abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion after a police raid in 1972 but the case was ultimately dropped after Roe v. Wade made abortion legal nationwide.

The perilous status of Roe v. Wade, Lessin argues, helped prompt some of those involved with Jane to open up. “I think the women of Jane who’d been reluctant in the past to speak about their experiences were pretty eager to come forward at this time because it was such a crossroads for abortion rights in America,” she said.

Speaking to THR, Lessin and Pildes talk about the challenges of capturing the voices of the women who were involved with and used Jane, including how they themselves used a Jane-like ad to find people; how they hope their film highlights the humanity behind a controversial issue; and why the film is mostly free of the current political arguments around abortion.

Did you imagine when you started working on The Janes that this film could be coming out at a time when Roe v. Wade could be potentially overturned?

Emma Pildes: Nothing we could have done could have so precisely landed us premiering on HBO in the same month that Roe is going to be overturned — that is just an unfortunate truth of the timeline this film. Certainly it’s sort of unimaginable in a lot of ways, no matter how grim everything was looking. The idea of Roe being overturned I think is still something that we can’t quite wrap our head around, although we know it’s certainly definitely going to happen. For a couple of years now, we’ve been working on this film and that’s sort of the place we’ve been: Hyper-aware and spurred on by all the things that were happening in the news cycle, with the high court and at the state level. It was still quite stunning just a few weeks ago to see the leaked decision. You can’t believe it’s true. It’s a nightmare.

Talk to me a little bit about the process of getting in touch with the various women who were involved with Jane. Were they willing to talk? How did they feel about revisiting this part of their lives? Were there any that were difficult to get in touch with?

Tia Lessin: There were, unfortunately, a number of the Janes who died in recent years — they were women in their 70s and 80s and some of them were sick. The biggest challenge was conjuring their voices in that absence. We were lucky enough to stumble on an interview that Dorothy Fadiman, the Oscar-nominated filmmaker, had conducted with two key Janes, Jody and Ruth, back in 1995 before they died, and she’s generous enough to give us that interview.

Most of the other Janes that we’ve spoken with — and, gosh, there are more than a dozen in the film — came on board at various times. There’s certainly a baseline of trust that Emma and Daniel had with these women because they have a family connection to the story, so they really trusted us to do right by them and by this story. But even so, some of them were telling this story for the very first time, not only to our cameras but also many of them hadn’t even told their families about their involvement in this illegal underground group. So it was quite something for them to speak so vividly about that time and their involvement and some of them, many of them about their own personal experiences with abortion in their own lives.

The hardest challenge was finding the women who’d used the service, bmecause the Janes took an oath of secrecy and they weren’t about to share names with us. We had to do a lot of digging, and I had this great idea of putting an ad in the local Chicago paper. And through that ad we found Dorie Barron, who tells the harrowing story of her abortion with the mob and then, later in the film, her version of Jane, which was an altogether different experience. We also wanted to interview the many layers of support that the Janes had around the city of Chicago — husbands and people who lent their apartments and lawyers and doctors who assisted. This was very much a community enterprise. This was not just a small group of women. This was a big endeavor on the South Side of Chicago.

Were there any specific individuals or people who would have provided a certain perspective that you wanted to talk to but weren’t able to?

Pildes: We respect so much the decision to not want to get in front of the camera 50 years later and talk about illegal activity from the ’60s. I don’t know if we want to call people out by name. We got what we needed. So many of them were willing to do it; it was a chorus of voices, some speaking for the ones that didn’t want to get in front of the camera. I feel good that there are so many of them that were willing to — another act of courage, a follow-up to their activity in the ’60s and ’70s.

One of the people who passed away who would have been so fantastic to include, though I do think the Janes do a good job of evoking her spirit in the film, is the criminal attorney who helped them when they got busted. Judith in the film describes her with her canary yellow outfit and her canary yellow briefcase and her brilliant mind and her smarts and toughness. People just love her, and she’s not even in the film. I can’t imagine what she would have done onscreen. That was a loss.

But that’s one of the other reasons why we felt it was so important to make this film as soon as we could because that’s the reality of making documentaries, is that people pass away and then those stories aren’t documented. So we just feel incredibly lucky and humbled that these women were willing to do this and that we captured this extraordinary story about extraordinary women.

One of the things that struck me when I was watching the film: The abortion debate now is so caught up in not only politics but also religious beliefs and people talking about “morality” and “Is it murder?” And so many of the women in this film were so pragmatic and practical — they felt like these were women in trouble and they wanted to help them. What do you make of this absence of the current parameters around the abortion debate?

Lessin: They felt a moral obligation, as Jody states [in the film], to disrespect a law that disrespected women. They felt like they were on the moral high ground in supporting women’s lives and helping women carry out decisions that they had made. I think at that time, there wasn’t this infusion of doctrine in the decision-making about this medical procedure. Sure it was stigmatized because sex outside of marriage was stigmatized, but this had happened really before the Catholic church and the evangelicals had sort of hijacked this issue.

And the Clergy Consultation Service, which was active not only in Chicago but also all over the country, was a network of Protestant and Jewish religious leaders that not only were outspoken about abortion rights, but also actually helped women terminate unwanted pregnancies and referred many women to the Janes. A lot of the Janes came out of the Catholic church, they were raised in the Catholic church. Many, many women that they offered services to were Catholic. They were also Jewish women.

They were women of deep principle who had come out of the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement and the student movement and those were their values: fighting for racial justice, fighting an unjust war and fighting for women’s liberation. The work that they did was entirely consistent with those values.

What do you hope people take away from this documentary, particularly people who maybe didn’t have strong feelings about the subject but were moved by the film? There are some very powerful and harrowing stories told.

Pildes: I think we hope that people remember that these are real women that are going to die and be injured when Roe is taken away. Real human beings. Mothers to other children, daughters, sisters, co-workers, best friends. Real people are going to die. That’s going to be a stunner as we see how criminalizing abortion shakes out, because we’ve been having these debates for so long and everybody’s at work trying to fight for their side. But now we’re going to see what it really looks like, and it’s grim.

That’s part of one of the things that we wanted to show with the film: In no uncertain terms what the country looks like when women don’t have a right to choose, when they’re driven into back alleys or forced to take matters into their own hands. We hope that we’ve injected some humanity back into the conversations about this because we’re going to see it, and we hope that wakes people up and reminds them they have to speak up now and they have to do something, and they have to help these women. Whether it’s financially or protesting in the street or however else you want to organize, it’s time now.