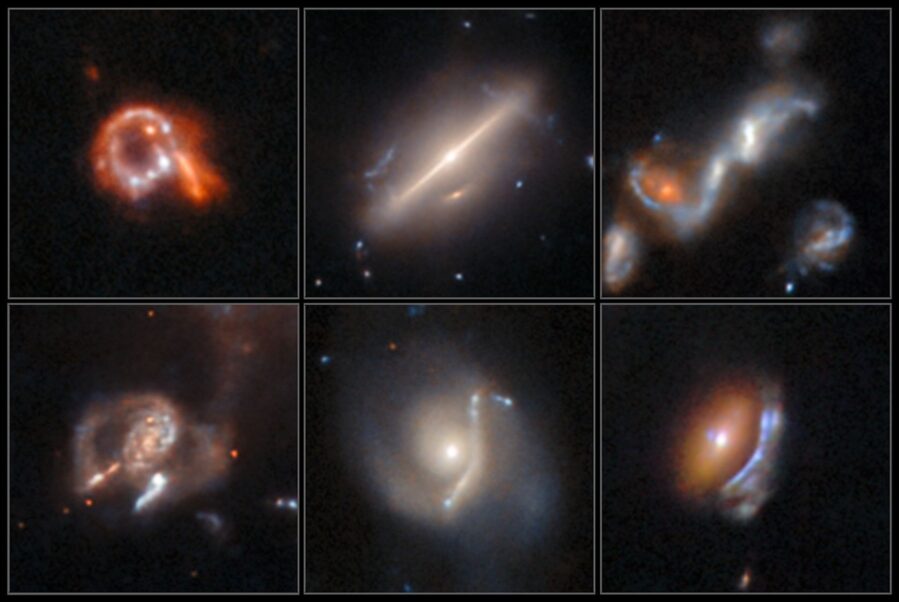

The algorithm took two and a half days to do what would have taken human astronomers years, maybe decades. Trawling through nearly 100 million images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the neural network flagged galaxies that looked, well, wrong. Galaxies twisted into question marks. Galaxies wearing halos of distorted light. Galaxies that seemed to be bleeding streams of stars into space. More than 1,300 cosmic oddities in total, and most of them, over 800, had somehow escaped notice in 35 years of Hubble observations.

David O’Ryan and Pablo Gómez, both at the European Space Agency, weren’t initially looking for such a menagerie. They’d set out to find edge-on protoplanetary disks, those rare “hamburger-shaped” systems where we can peer into the flat plane of a forming solar system. They started their AI hunt with just three examples; three tiny needles to find in a haystack of 100 million images.

But their algorithm, which they call AnomalyMatch, had other ideas. During its training runs, it kept flagging things that weren’t protoplanetary disks at all. Galaxies mid-collision, their spiral arms shredded into tidal streams. Gravitational lenses where massive foreground galaxies warp spacetime enough to smear background galaxies into arcs and rings. Jellyfish galaxies with tentacles of gas streaming behind them as they plough through dense galactic clusters.

O’Ryan and Gómez decided to follow where the algorithm led. They expanded their training set to include these serendipitous discoveries (mergers, lenses, jellyfish) and let AnomalyMatch loose on the full archive. “Archival observations from the Hubble Space Telescope now span 35 years, offering a rich dataset in which astrophysical anomalies may be hidden,” says O’Ryan. Hidden they were, but perhaps not anymore.

The haul is substantial. From their top-ranked detections, the team confirmed 629 galaxy mergers or interactions, 140 candidate gravitational lenses, 35 jellyfish galaxies being stripped of their gas, and those elusive edge-on protoplanetary disks they’d originally sought – though only two more beyond what was already known. Several dozen objects defied classification entirely, their morphologies so bizarre they don’t fit into existing categories.

What makes this impressive isn’t just the numbers, it’s the efficiency. Training the neural network on 1,400 labeled images and roughly 99,000 unlabeled ones took less than four hours on a graphics processing unit. Scanning all 100 million cutouts from the Hubble archive took just 2.5 days. And about 65 per cent of the anomalies the algorithm identified had never appeared in scientific literature before, despite Hubble being one of the most scrutinised astronomical datasets in existence.

The approach fills a peculiar gap in how we hunt for cosmic rarities. Traditional methods rely on expert astronomers manually examining images or stumbling upon oddities during unrelated observations. That works when datasets are manageable, but Hubble has been snapping photos for over three decades. Citizen science projects help. Galaxy Zoo and similar efforts have recruited thousands of volunteers to classify galaxies, but they still can’t keep pace with archives this vast, let alone with what’s coming next.

Because the data deluge is only beginning. ESA’s Euclid mission, NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will generate terabytes of images every night. We’ve never had such volume of observational data in astronomy’s history, and human eyes, even many thousands of them, simply can’t review it all.

AnomalyMatch sidesteps that limitation through semi-supervised learning. Unlike traditional AI approaches that need huge training sets of prelabelled examples, it learns from a tiny number of anomalies alongside vast pools of unlabelled data. The algorithm assigns each image an “anomaly score” between zero and one, then O’Ryan and Gómez review the highest-scoring candidates to confirm real discoveries. That human-in-the-loop approach lets expert knowledge guide the AI’s learning, while the AI handles the tedious work of scanning millions of images.

The method is remarkably flexible, too. O’Ryan and Gómez didn’t have to train separate algorithms for each type of anomaly. A single network learned to recognise “weirdness” in general, flagging gravitational lenses, mergers, and jellyfish galaxies even though it was initially trained only on protoplanetary disks. Some discoveries surprised them. They found lensed quasars, those rare Einstein Cross configurations where a background quasar is split into four bright points around a foreground galaxy, despite never training the algorithm on such objects.

That adaptability matters because we don’t always know what we’re looking for. The most interesting discoveries in astronomy often come from finding things we didn’t expect to find. An algorithm that can spot “anomalous” without being told exactly what anomalous means might catch phenomena we haven’t even thought to search for yet.

“This is a powerful demonstration of how AI can enhance the scientific return of archival datasets,” says Gómez. The Hubble archive isn’t just a historical record – it’s an active resource for discovery, with treasures still buried in decades-old observations. And Hubble isn’t unique. Every major telescope generates archives that vastly exceed our capacity to analyse them fully.

The team used ESA’s Datalabs platform, which gives researchers direct access to telescope archives without requiring massive data downloads. That infrastructure advantage mattered – handling 100 million images would have been prohibitively slow without it. As AI tools like AnomalyMatch become standard, that kind of computational infrastructure will be essential.

Not everything the algorithm flagged turned out to be scientifically interesting, mind you. The contamination rate – normal objects mistakenly scored as anomalous – ran about 10 per cent. Star fields from dense globular clusters or the Andromeda galaxy sometimes fooled it. Some high-scoring objects were too small or too noisy to classify with confidence. A handful turned out to be imaging artifacts rather than real cosmic structures.

But even with that false positive rate, AnomalyMatch’s precision exceeds what’s possible with purely automated approaches. And the misses are informative, too, helping refine what the algorithm considers anomalous versus merely unusual. Through iterative training – adding newly confirmed examples back into the training set – the network’s accuracy steadily improves.

What’s particularly striking is how much Hubble has observed without astronomers fully realising what they had. These weren’t images from neglected corners of the archive. They came from mainstream observations, often of well-studied targets. But the anomalies were in the background, or in fields adjacent to the primary target, or hiding in plain sight amid thousands of other galaxies. Human attention is limited. We look for what we’re looking for, and we miss the rest.

That’s where AI excels – in systematic, exhaustive surveys without the attention biases that humans inevitably bring. O’Ryan and Gómez’s work shows that even well-trod archives contain discoveries waiting to be made, if only we look with fresh eyes. Or, in this case, with neural networks that don’t know what they’re supposed to ignore.

The implications extend beyond Hubble. James Webb Space Telescope observations, Euclid’s billions of galaxies, Rubin Observatory’s nightly sweeps of the entire visible sky – all will generate archives orders of magnitude larger than what we have now. Tools like AnomalyMatch won’t just help; they’ll be necessary. Finding rare phenomena in that scale of data is impossible otherwise.

And perhaps the most intriguing aspect is the unknown category – those several dozen objects that don’t fit any existing classification. What are they? Some might be extreme examples of known phenomena, pushed to morphological limits we haven’t seen before. Others could represent genuinely new categories, cosmic structures or processes we haven’t identified yet. Without the AI scan, we likely wouldn’t have found them at all. Now they’re sitting in a catalogue, waiting for astronomers with the right expertise to figure out what, exactly, they’re looking at.

The future of astronomical discovery might look something like this: AI algorithms scanning archives continuously, flagging anomalies for human review, learning from each round of expert validation, steadily expanding our catalogues of rare phenomena. Not AI replacing astronomers, but AI extending their reach, letting human expertise focus on the most interesting targets rather than drowning in the routine work of scanning millions of images.

O’Ryan and Gómez have released their full catalogue of discoveries – all 1,339 objects, complete with coordinates and classifications – for the astronomical community to study. That includes the 811 that appear to be entirely new to science. Plenty of work ahead for those who want to follow up on gravitational lenses that might probe dark matter distributions, or jellyfish galaxies that reveal how galaxy evolution proceeds in dense environments, or those mysteriously unclassifiable objects that might be telling us something we don’t yet know how to hear.

Study link: https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55512-25/aa55512-25.html

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!