The James Webb Space Telescope plans to explore strange, new rocky worlds in unprecedented detail.

The telescope’s scientific consortium has an ambitious agenda to study geology on these small planets from “50 light-years away”, they said in a statement Thursday (May 26). The work will be a big stretch for the new observatory, which should exit commissioning in a few weeks.

Rocky planets are more difficult to sight than gas giants in current telescope technology, due to the smaller planets’ relative brightness next to a star, and their relatively tiny size. But Webb’s powerful mirror and deep-space location should allow it to examine two planets slightly larger than Earth, known as “super-Earths.”

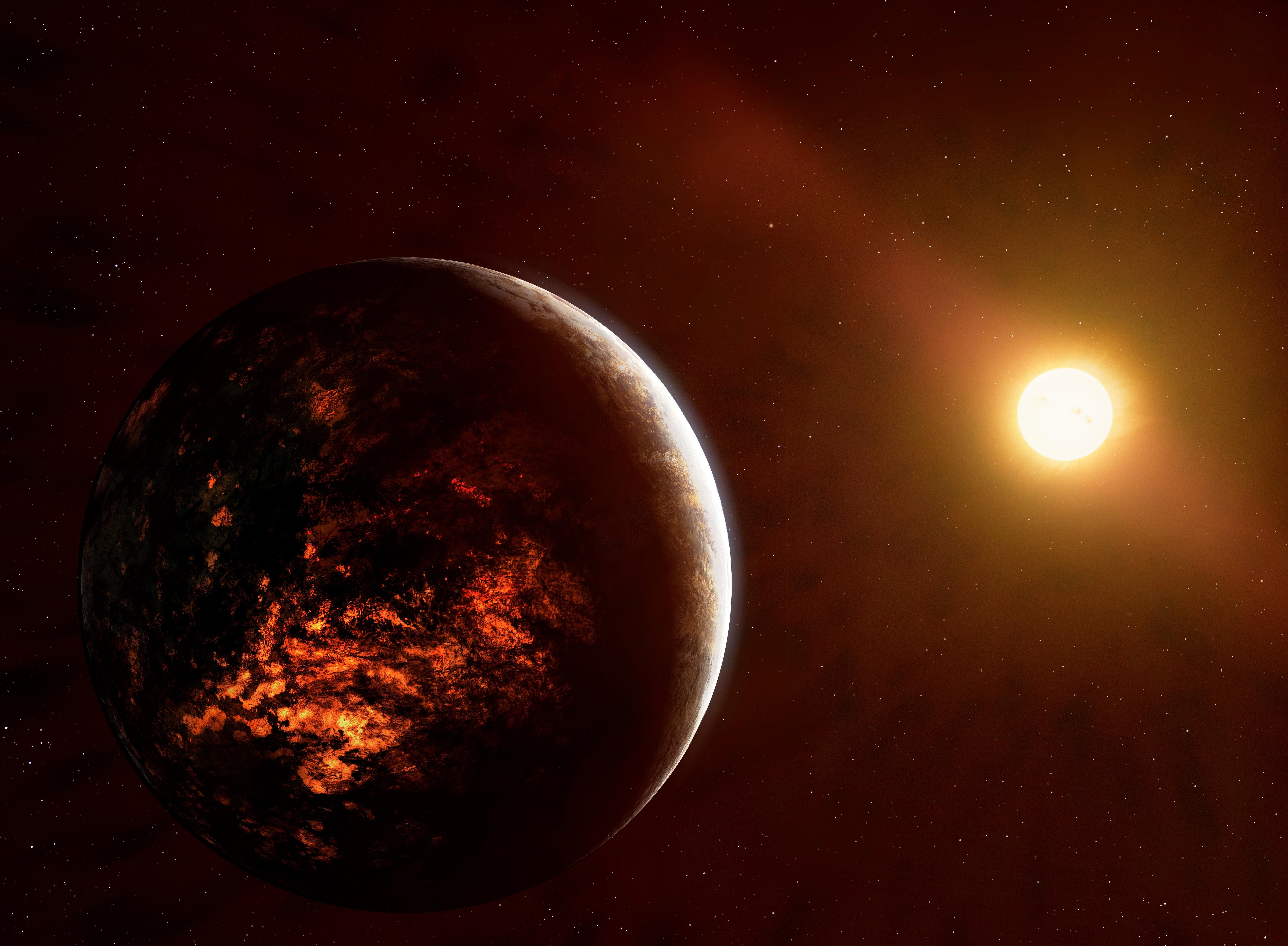

Neither of these worlds is habitable as we know it, but investigating them could still be a proving ground for future in-depth studies of planets like our own. The two planets Webb officials highlighted include the super-hot, lava-covered 55 Cancri e, and LHS 3844 b, which lacks a substantial atmosphere.

55 Cancri e orbits its parent star at a tight 1.5 million miles (2.4 million km), about four percent of the relative distance between Mercury and the sun.

Circling its star only once every 18 hours, the planet has blast furnace surface temperatures above the melting point of most types of rocks. Scientists also assumed the planet is tidally locked to the star, meaning one side always faces the scorching sun, although observations from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope suggest the hottest zone might be slightly offset.

Scientists say the offset heat might be due to a thick atmosphere that can move heat around the planet, or because it rains lava at night in a process that removes heat from the atmosphere. (The nighttime lava also suggests a day-night cycle, which might be due to a 3:2 resonance, or three rotations for every two orbits, that we see on Mercury in our own solar system.)

Two teams will test these hypotheses: one led by research scientist Renyu Hu of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory will examine the planet’s thermal emission for signs of an atmosphere, while a second team led by Alexis Brandeker, an associate professor from Stockholm University, will measure heat emittance from the lit side of 55 Cancri e.

LHS 3844 b is also a close orbiter, moving around its parent star just once every 11 hours. The star, however, is smaller and cooler than that of 55 Cancri e. So the planet’s surface is likely much cooler, and Spitzer observations have shown there is likely no substantial atmosphere present on the planet.

A team led by astronomer Laura Kreidberg at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy hope to catch a signal of the surface using spectroscopy, in which different wavelengths of light suggest different elements. Thermal emission spectrums of the planet’s daylight side will be compared to known rocks like basalt and granite to see if they can deduce a surface composition.

The two investigations “will give us fantastic new perspectives on Earth-like planets in general, helping us learn what the early Earth might have been like when it was hot like these planets are today,” Kreidberg said in the same statement.

Webb is now working through latter-stage commissioning procedures like tracking targets in the solar system and moving between hotter and colder attitudes to test the strength of its mirror and instrument alignment. The $10 billion observatory should finish its commissioning around June or so and move into its Cycle 1 of observations shortly afterwards.

Copyright 2022 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.