For more than a century, Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity has shaped our understanding of gravity and the universe’s most extreme objects: black holes. But what if not all black holes are created equal? A new study from physicists at Goethe University Frankfurt and the Tsung-Dao Lee Institute in Shanghai suggests we may soon have the tools to find out.

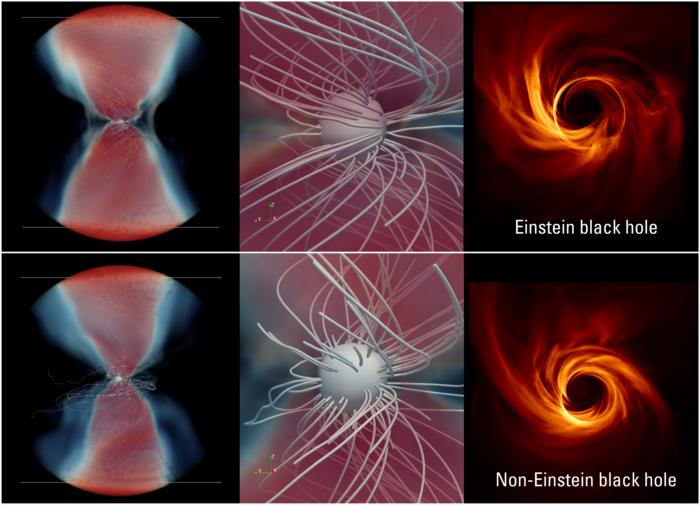

Their research, published in Nature Astronomy: 10.1038/s41550-025-02695-4, uses advanced computer simulations to predict how black holes would appear under different theories of gravity. The goal: to compare those models with actual images captured by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), the global array of radio telescopes that produced the first-ever images of supermassive black holes in the galaxies M87 and our Milky Way.

Seeing the Unseeable

Physicist Luciano Rezzolla, a co-author of the study, describes the EHT’s achievement with vivid precision. The telescope array does not capture the black hole itself, he notes, but rather the bright, swirling plasma just beyond its point of no return. Those luminous gas streams trace the “shadow” of the black hole, revealing its gravitational footprint against the surrounding light.

“What you see on these images is not the black hole itself, but rather the hot matter in its immediate vicinity,” said Rezzolla. “As long as the matter is still rotating outside the event horizon, before being inevitably pulled in, it can emit final signals of light that we can, in principle, detect.”

That shadow, it turns out, is more than just a cosmic portrait. It is a testable prediction of Einstein’s equations. But according to Rezzolla and lead author Akhil Uniyal, other, more speculative theories also predict black holes, some that might differ subtly in shape or size, depending on how gravity behaves in their models.

When Shadows Speak Physics

The team simulated these differences using three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic models that mimic how matter and light behave near black holes. Their findings suggest that while current EHT images are too low in resolution to distinguish Einstein’s black holes from their exotic alternatives, the next generation of telescopes could change that dramatically.

“The central question was: How significantly do images of black holes differ across various theories?” explained Uniyal. “With future high-resolution measurements, we could often make a decision in favor of a specific theory.”

The study predicts that as telescope resolution improves, especially with the addition of orbital instruments that expand Earth’s virtual lens, scientists will be able to detect image mismatches as small as 2 to 5 percent. That is enough, the authors argue, to confirm or rule out entire classes of gravitational theories. The EHT’s eventual goal is to resolve details smaller than one millionth of an arcsecond, comparable to spotting a coin on the Moon from Earth.

For now, Einstein’s theory remains unbeaten. But Rezzolla emphasizes that this is precisely why testing it matters: only by trying to break a theory do we discover whether it still holds. In a few short years, we may finally see whether black holes, those cosmic gluttons devouring light itself, are all cut from the same spacetime cloth.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!