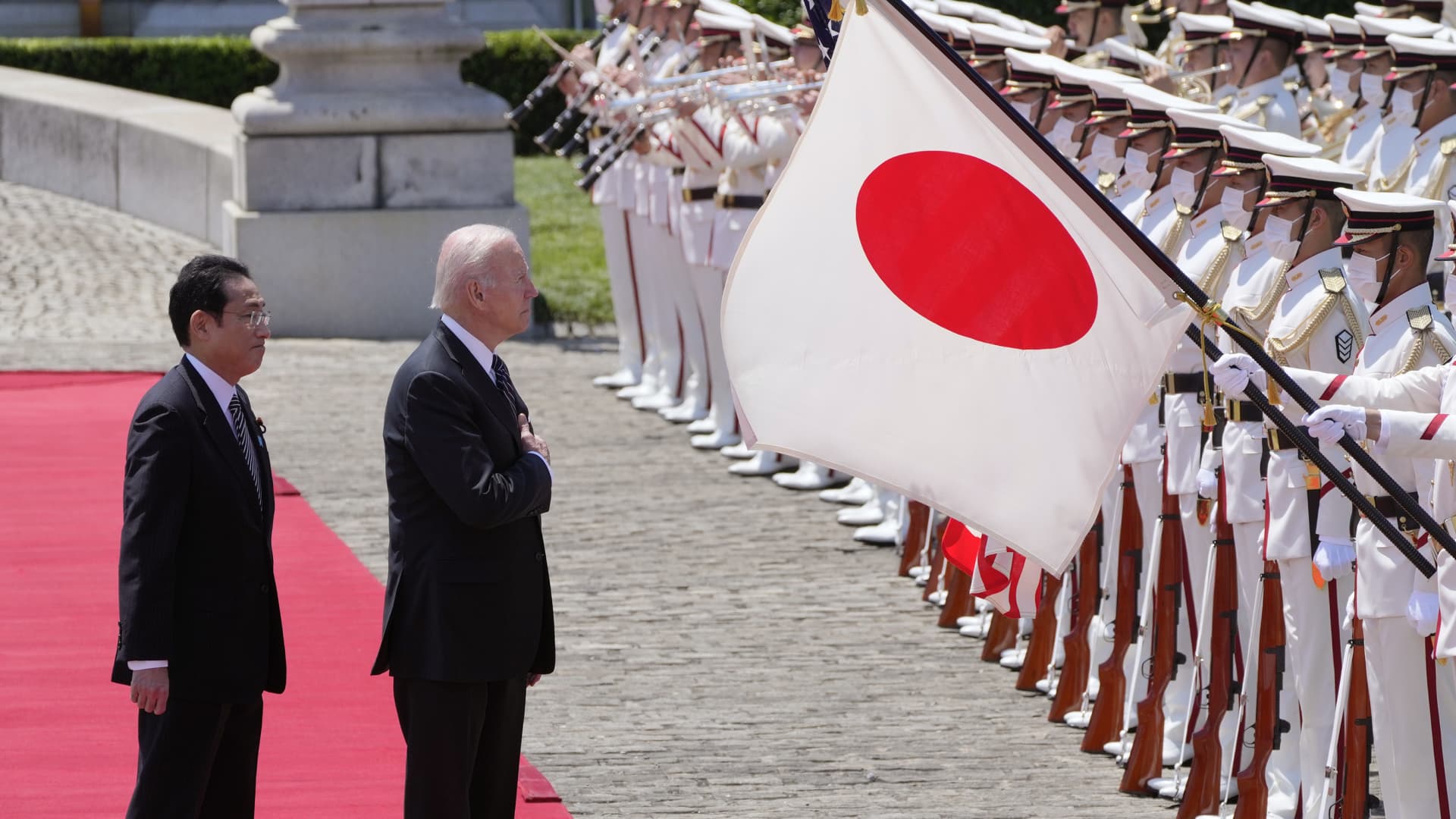

U.S. President Joe Biden (R) here seen reviewing an honor guard with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in Tokyo, released an economic framework during his visit to Japan last week. The IPEF came as a lifeline for India, which had stayed out of a China-centric pact consisting of Southeast Asian nations in 2020.

Pool | Getty Images News | Getty Images

Two years after walking out of a China-centric free trade pact in Southeast Asia, India is embracing the chance to become a founding member of another grouping — this one led by the U.S.

The launch of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework in Tokyo during President Joe Biden’s first official trip to Asia last week gives India a chance to make its own pivot to the Pacific.

New Delhi’s move to solidify its alliance with Washington comes amid news that the U.S. overtook China to become India’s largest trade partner in the fiscal year ending March 2022.

Except for India and the U.S., all other nations participating in the IPEF launch are part of a rival bloc, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. RCEP includes China, which is the largest trade partner of most pact members.

India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar later affirmed India’s commitment to IPEF. At a conference in India with Southeast Asian nations last week, he said India was building infrastructure to forge closer links to Southeast Asia through Myanmar and Bangladesh which would dovetail with the new framework.

“[Connectivity] will not only build on the partnerships that we have with Asean and Japan, but would actually make a difference to the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework that is now in the making,” Jaishankar said.

Countries in the [Indo-Pacific] region can overcome geography and rewrite near history if they get policies and economics right.

Subrahmanyam Jaishankar

external affairs minister of India

“Countries in the [Indo-Pacific] region can overcome geography and rewrite near history if they get policies and economics right,” he noted.

Both Bangladesh and Myanmar are part of the Belt and Road Initiative under which China has plowed billions of dollars into infrastructure projects across continents. India has stayed out of President Xi Jinping’s signature initiative because of an ongoing border dispute. Besides, a key component of the BRI passes through areas of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. India claims all of Kashmir as its own.

Excluding China

India’s early fervor for the IPEF is an about-turn for the South Asian giant, which chose to stay out of the China-centric RCEP which kicked off earlier this year. The RCEP includes Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and the 10 Southeast Asian nations, making it the world’s largest free trade pact.

“A major flaw of RCEP was the inclusion of China,” former chief economic advisor to the Indian government Arvind Virmani told CNBC. “China agrees to everything on paper, but has no compunctions about evading rules in practice. IPEF is very attractive to India because it includes east & southeast Asian countries but excludes China,” he said.

China which last week criticized the the IPEF as an effort “doomed to fail,” dismissed it again on Monday.

“How can it be called inclusive if it purposefully excludes China, the largest market in the region and in the world?” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi asked. Wang made the comment during a visit to Fiji, which became the newest member to join IPEF last week.

Although IPEF is not styled as a trade pact, trade is one of its four pillars. The other pillars are supply chain resilience; clean energy, decarbonization, and infrastructure and finally, taxation and anti-corruption.

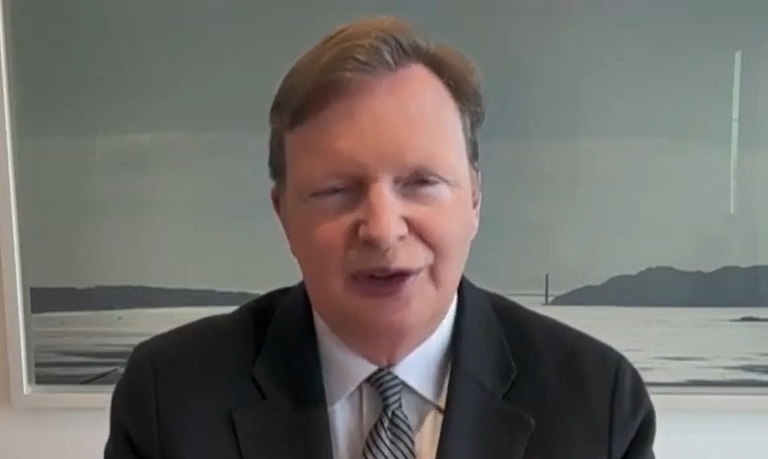

“India will gain from signing up for a multilateral framework which will mean some standardization across sectors,” a former industry secretary to the Indian government, Rajan Katoch, told CNBC from Bhopal, a city in central India.

“I hope it leads to something (on trade) because that will put pressure on the Indian system to be more open. India is too protectionist, in my view, considering the capabilities its people have,” Katoch said, adding that the IPEF could enable India to push for supply lines for some products to be moved to India.

But strategic calculations could outweigh economic considerations. “It’s becoming a very segmented world and you have a foot in this camp… you want that to be seen also,” Katoch said.

India-China tension

India’s aversion to a pact which includes China has geopolitical considerations at its root. Tensions on India’s Himalayan border with China erupted into a bloody conflict two years ago. Tens of thousands of soldiers from both sides are still deployed on the border.

Katoch said although lowering barriers to U.S. markets is not currently on the table at this stage, that could eventually change through negotiations.

“Maybe [negotiations could result in] some reduction in barriers or some encouragement of supply chain relocation to India. I suppose that’s the way it would go,” he said.

But India’s importance to the U.S. is more strategic than economic. As the only Asian country that shares a disputed land border with China and is strong enough to stand up to the emerging superpower, India is a key component of the U.S.’ Indo-Pacific strategy to contain China. That strategic confluence may lead to concessions on both sides.

The very notion of an Indo-Pacific is hollow without Indian participation.

Joshua P Meltzer

senior fellow, Brookings Institution

“The very notion of an Indo-Pacific is hollow without Indian participation,” Joshua P. Meltzer, a senior fellow in the global economy and development program at the Brookings Institution, said in a recent analysis. He added India may be more accepting of IPEF than RCEP since it does not make any demands to lower tariffs.

“The IPEF also comes at a time when India has clarified its strategic concerns with respect to China. Increasing China–Russia alignment may also lead India to seek even closer relations with the United States,” Meltzer said.